Source: iranwire.com

“Misguided sect.” You may have heard the term used by the government of the Islamic Republic to discriminate against and restrict large sections of Iranian society, who are Baha’is, so that they are deprived of their basic human rights from birth to death. The term is also cited in court rulings when Baha’is are imprisoned as a result of their beliefs. Baha’is are deprived of university and sometimes high school education, their businesses are constantly shut down, they are prevented from being employed in private companies and even their bodies are not allowed to be buried in public cemeteries. And while the Islamic Republic imposed these restrictions and executed more than 200 Baha’is when it came to power, the elimination of “others,”, especially the Baha’is, has a longer history than the Islamic Republic.

Fereydoun Vahman, a linguist, researcher and author of the book 175 Years of Persecution: A History of the Babis & Baha’is of Iran, Mahvash Sabet, one of seven Baha’is jailed between 2008 and 2018 for administering to the affairs of the community, Erfan Sabeti, a researcher and sociologist, Simin Fahandej, spokesperson for the Baha’i International Community at the United Nations, Shabnam Tolouei, director and actor, Sepehr Atefi, journalist and member of a Baha’i family that has lost some members to state executions, and Mahnaz Parakand, a human rights lawyer, met on Clubhouse recently to discuss the Islamic Republic’s persecution of the Baha’is and its insistence on labelling them an “errant sect.” Human rights activist Assieh Amini and IranWire journalist Aida Ghajar moderated the session.

The meeting was held in the “government-made taboos” room at the “Ayeneh [Mirror]” Clubhouse channel. The channel is hosted by the lawyer and Nobel Peace prize laureate Shirin Ebadi, Assieh Amini and Aida Ghajar every two weeks, to look at concepts created by the Islamic Republic, used for its political purposes and aligned with its ideology, and perpetuated by many people in Iranian society and intellectual circles.

A History of Persecution

The rights of the Baha’is have always been widely violated. Parts of these violations appear and reappear in the news, such as the deprivation of education, closures of businesses, imprisonments, land confiscations and even the destruction of Baha’i graves. But there is another part that is neither seen nor in the news: the complicity of large sections of Iranian society in slandering and spreading propaganda against the Baha’is. The complicity comes either through active perpetuation of such slurs or a tacit silence when encountering them – either way these add to the persecution suffering of the Baha’is.

Anti-Baha’i propaganda and tropes also pre-date the Islamic Republic – they were used during the Pahlavi and Qajar periods.

Fereydoun Vahman explained during the Clubhouse event that the word “errant” or “misguided” entered Iran’s religious culture after the arrival of Islam.

“This word originally meant a lost camel. But gradually it took on concepts such as being a vagrant, and in the Quran it also means misguided. The word has recently been translated as misleading. Today it is used especially for Baha’is, and exceptionally for mystics, Ismaeilis and Sunni Muslims. The term carries with it traits that [Iran’s clerics] have been promoting for more than two centuries. ‘Errant’ today brings to mind concepts such as infidel, atheist, apostate, unclean, anti-religious, degeneracy in sexual relations and the like. This word has a background in our history and is not unique to Islam.”

Vahman also addressed the antecedents in Iran’s ancient history from a theological and sociological point of view: “Labelling some parts of society as ‘misguided,’ on a religious basis, has happened many times. Most social innovations are political developments in the guise of religion and for the sake of religion or in opposition to religion. The history of Iran has been religious from ancient times to the present day. It was the same before the Sassanids [who ruled Iran from the 3rd to the 7th centuries CE]. When the Sassanids came to power, they found a society with various Zoroastrian, Christian and Jewish alliances. Zoroastrian clerics enacted laws to unify society and to put the Zoroastrian religion at the service of the country’s politics. For this reason, the Zoroastrians quickly became anti-Semitic. This … played an important role in the relations between Iran and the [Christian] Eastern Roman Empire and caused wars that lasted for several centuries and that ultimately ended the Sassanid dynasty. The Sassanids wanted to propagate the Zoroastrian religion and to conquer other countries. So did the Roman emperors. They used religion as an excuse to conquer territories, but by killing people, they made people hate religion. That is why, when Islam entered Iran, many Iranians embraced it; because they had survived the oppression of the Zoroastrians.”

Others, Together

Mahvash Sabet returned to the days of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, in her remarks, when she was 25 years old and a teacher: “I had fewer worries in those days; I was optimistic and felt that we [Iran] would show that we are peaceful and religious. … But we faced many problems in Iran. When I was fired after the Cultural Revolution in 1980, I joined a committee to look after expelled students. All over Iran, [Baha’i] university students and final year high school students were expelled. Panic and anxiety crept into the Baha’i community. Despite my optimism, I was convinced we were in trouble.”

Mahvash Sabet later joined the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education, an informal or “underground” university created by the Baha’i community in 1987, to offer higher education to young Baha’is denied access to university. Sabet worked in this educational institution for 19 years. For her, the expulsion or barring of students from university became a focal point in the spiritual life of the Baha’is which showed their independence and resilience to the rest of the world. Sabet was imprisoned for her activities. But it was also an “opportunity” for her: “The mental barrier between us and other Iranians came down in prison. We were in the prison wards with political prisoners and educated and activist men and women. Some wanted to separate their clothes from us because they thought we were ‘unclean’. But after a while they apologized for this and became close friends. It was in prison that we got to know each other. Our most honest experiences during these years took place in prison.”

A culture of othering minorities – and developing stigmas and taboos around them – had been systematically developed and institutionalized in Iran. But, in Sabet’s experience, these prisoners became a transformed microcosm of Iranian society. For years Iranians kept silent as the Islamic Republic repressed and persecuted the Baha’is – now here was a glimpse of something different.

Breaking the Anti-Baha’i Taboo

Iran’s Defenders of Human Rights Center, established by Shirin Ebadi, was meanwhile one of the organizations that also broke this taboo by contacting the Baha’i community and offering to represent them in court.

Commenting on this, Ebadi said: “The Defenders of Human Rights Center was sensitive to the issue of the Baha’is from the beginning. [Confronting] religious discrimination has always been important to us. When seven leaders of the Baha’i community in Iran were arrested, I accepted their representation and, as always, invited several lawyers to join us. We knew that each of us could be arrested for our work. Mahnaz Parakand and Abdolfattah Soltani joined me. Before taking the case we had also represented a number of [Baha’i] students who had been expelled from university. But unfortunately, despite the fact that the law does not prohibit their education, we have not been able to secure the rights of these young people. My clients were pressured to fire me, and the authorities tried to dissuade me from pursuing the case in various ways. For example, they spread the rumor that Ebadi is changing her religion and, according to the archaic laws of the Islamic Republic, this would be severely punished. This rumor started in Kayhan newspaper. I felt it was a trap to force me to step aside. That is why I wrote a letter to Ayatollah Montazeri [a prominent cleric] and asked whether a Muslim lawyer could defend a non-Muslim. He responded positively, saying that if a lawyer knows their client is innocent, then the lawyer has a duty to defend their client. … But I was not allowed to read the Baha’i case file for a year and four months.”

According to the laws of the Islamic Republic, while a case remains under active investigation, the lawyer has no right to read the files or meet with clients who continue to interrogated. Ebadi said that the case investigator, following her attempts to see the files, asked why she was defending the Baha’is. “The people of this errant sect are misleading our youth,” the investigator said. “I regret that the law does not allow it, but if it were allowed, I would have also killed their children.”

Ebadi had no choice but to wait for the case to be handed over to her. “Seven people [the Baha’is] had been accused of espionage and acting against national security. The reason was their connection to Israel. I should mention that the administrative and religious center of the Baha’is is the Universal House of Justice in Israel. When the prophet of the Baha’i faith, Baha’u’llah, passed away, there was no such country as Israel and Palestine was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. The Qajar government had exiled Baha’u’llah to Palestine and he died there. According to the Baha’i faith, a person must be buried where they die. The accusation against these seven Baha’is, meanwhile, was that they were in contact with the House of Justice. There was no evidence [for this] in the case against my clients. The trial began after 2009 [and the protests following the contested presidential election] and I was not in Iran. My colleagues attended the trial and we consulted each other as it proceeded. My innocent clients were sentenced to a total of 20 years in prison. The longest single sentence within this ruling was for a decade, so legally, they had to serve the longest sentence and were in prison for the full 10 years of their sentences.”

Being a member of the “errant Baha’i sect” has been used as an accusation against Baha’i citizens since the Islamic Republic came to power. In February 2019, Reporters Without Borders said it had obtained a document, via the United Nations, from the judiciary of the Islamic Republic identifying more than 1.7 million people who had been arrested, imprisoned and executed between 1979 and 2009. Shirin Ebadi was among the members of the committee that verified this document. The document shows that in 30 years, 5,760 Iranian citizens in Tehran alone were prosecuted or arrested on charges of membership in the “errant Baha’i sect” and some were executed.

The Silent Majority

But how has anti-Baha’i sentiment and propaganda been helped through the silence or complicity of Iran’s wider society? What accounts for this silence?

Erfan Sabeti said: “In the Bible, the Gospel of Mark, we read that Jesus told Mark not to be a dishonorable prophet, except in his own country, among his own relatives and in his own house. A similar concept was written by the Renaissance thinker Michel de Montaigne in one of his famous essays; that a man can be a wonder of the world, while his wife and his servants do not see anything significant in him. Few people have surprised their families, and many people are interesting, but if they are close to us in space and time, we probably do not take them seriously, because people often have a bias against whoever is alive and present. I am referring especially to the intellectual class. Look at the remarks of contemporaries and historians such as Tolstoy and Sarah Bernard, famous in the 19th century, praising the Bab [the founder of Babi faith, precursor to the Baha’i faith] and compare them to the criticism of the Bab’s compatriots such as Fereydun Adamiyat and Ahmad Kasravi.”

Sabeti cited Kasravi and the book Bahaiism: “Kasravi said the Bab had a disturbed mind, was dumb, impudent, helpless, exaggerated, a liar, ignorant, foolish, nonsensical, short-sighted and stupid. He also said that Tahereh Qurat ul-Ein [a famous Babi and celebrated Iranian poetess of the 19th century] had a disturbed mind. He said that women are seduced quickly and the farther they are from Iran the better. He said this in the book Our Sisters and Daughters. Even Fereydun Adamiyat, a well-known Iranian secular historian, did not stop there; he forged a document and claimed in his book Amir Kabir and Iran that Mulla Hussein, the first person to believe in the Bab, was a British agent and a spy. Adamiyat claimed that he has documents to prove this charge. But the meeting [with the British] that Adamiyat claims took place cannot have done so because Mullah Hussein was just 16 years old at the time of the alleged meeting while the Bab was only 11 years old.”

Intellectuals and scholars therefore played a role in creating the taboo around Baha’is and the notion that they are a “misguided” or “errant” sect in the pay of foreign powers.

The Personal Costs of Propaganda

Later in the meeting a note was read out, written by one Elham Habibi, a survivor of the Habibi family, several of whose members were arrested in 1981 along with five others from the Baha’i community in Hamedan during the first massacres of the 1979 Revolution, and were tortured in front of each other until they died. The authorities dumped their bodies in front of a hospital in Hamedan.

Elham, a young girl in high school with dreams for her future, before her world changed, said in this note: “On the eve of my adulthood, for the hundredth time, I turn the pages of my notebook; maybe, in the corners of memories, there will be something that will calm my heart. Every time [in these pages] I see a passionate and hard-working teenage girl with thousands of dreams, who lives with love, studies and gets ready to go to university, and has plans to return to her community to serve. But all of a sudden, plans fail, and ambitious and aspirations remain a dream, because she is a Baha’i and, being a Baha’i, she is deprived of her basic rights. […] And still now, after years of remembering the execution and loss of my father and being deprived of education, my heart is so saddened that it is impossible to say. There is not even a place for us to go to their graves to pray. Never, never, never, and at no point in my life did these wounds heal, and its effects will dominate my soul as long as I live.”

Simin Fahandej, a Representative of the Baha’i International Community to the United Nations, was also in the meeting. “The term ‘errant sect’ is used not only in the media, textbooks and histories against the Baha’is,” she said, “But by representatives of the Islamic Republic in international forums who have also used this term to refer to Baha’is. When asked why Baha’is are persecuted in Iran they say the Baha’is are an ‘errant sect’ and are not recognized under Iran’s constitution. Baha’is are charged and convicted of the same slur in Iran’s courts. The term is used against Baha’is for two reasons. The first is that, by calling the Baha’is a sect, they deny them a religious identity, and the second is that the Islamic Republic has tried to justify the persecution of the Baha’is by trying to label them with such terms. Citizenship rights, however, are not based on religious beliefs, and every human being should have citizenship rights just because he or she is a human being.”

Fahandej also referred to “hatred” as a tool for authoritarian governments to oppress and persecute minority groups: “A new wave of persecution was imposed on the Baha’is after the 1979 Revolution. More than 200 Baha’is were executed in the first years of the Revolution. Thousands were arrested. In August 1980, nine members of the community’s National Spiritual Assembly, its elected governing body, were abducted and executed. A number of prominent members of the local Baha’i community were also arrested and executed. In 1983, Iran’s Attorney-General called for the dissolution of Baha’i organizations and the National Assembly dissolved itself in good faith. But with the start of the Revolution, Baha’i employees were fired from government and private employment, their pensions were cut, and some were forced to pay back their salaries. Baha’i properties and even cemeteries were looted.”

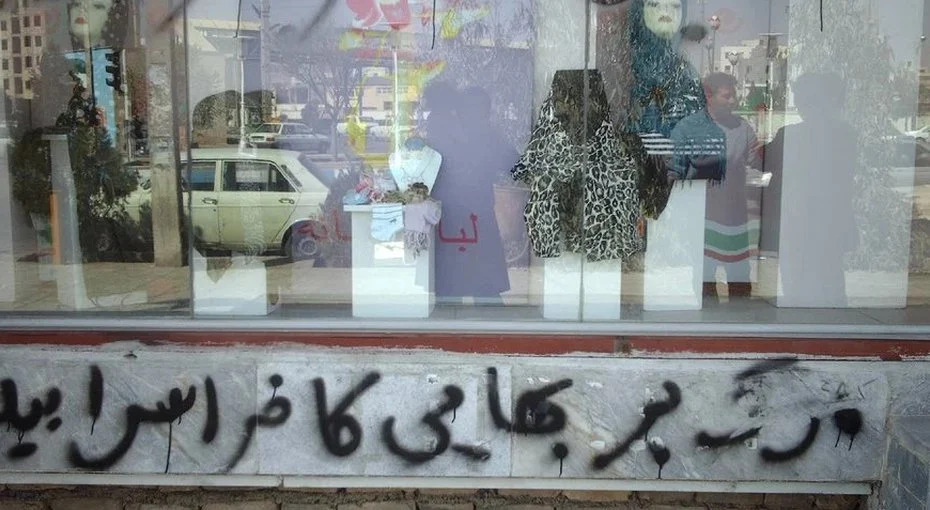

Shabnam Tolouei, another participant in the Clubhouse gathering, was banned from artistic activities in Iran because she is a Baha’i. She could no longer act so she left her homeland. “I had heard from my father, who was born in 1938, that they had migrated to one of the cities [in Iran] and after a week, they defaced the wall of their house with ‘God’s curse be on the errant sect.’ It was the first sign of anti-Bahaism for them. In 2014, Mohammad Javad Larijani [a prominent conservative politician] said the Iranian authorities do nothing to the Baha’is … I was among those who wrote to him. I grew up in a half-Muslim and half-Baha’i family [and experienced discrimination] … I think as long as the concept of minorities exists in Iran, in any group and with any description, such discrimination will continue.”

Tolouei related an event in the 1990s, when signs began appearing on grocery store windows advising whether a grocer was Christian, so that Iranians who thought Christians were “unclean” could avoid buying from their store. “We were the ones who went against the flow and bought from them,” Tolouei said. “I always thought I am neither a minority nor a majority, but simply an Iranian, and in the name of Iran, we should all have equal rights.”

Being a Baha’i is Not a Crime – Including in Islam

The next speaker in the event, Sedigheh Vasmaghi, an Islamologist, spoke to why Shia Muslim have been at odds with the Baha’is. “I was pleased to meet some Baha’is in prison and it helped me learn more about the suffering of my compatriots. They contribute to the cultural development of Iran with their perseverance and stability and the sufferings they have born. But is this antagonism and intolerance of other beliefs specific to Islam against the Baha’is? Or do we see it in other religions? It has been present in all religions – from ancient times to the present day. One of our mistakes in human society gas been religious bigotry and intolerance towards the followers of other religions. Muslims also did not accept the religion which emerged after Islam. Even in the Babi religion you see the same rejection of other religions … the Baha’i faith corrected this. This issue has traditional roots. But people have tried to correct these mistakes – just as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights’ tried to end discrimination. … In the Islamic world, jurists are a major obstacle to cultural development because they have failed to correct traditional and historical errors. Discourses such as peace, freedom and human rights are alien to our jurists.”

Vasmaghi also said human beings have a duty to correct the mistakes of the past. “Today, humanity has taken a big step forward and many people think we should not make human rights dependent on beliefs, gender and race. These are human achievements that are the result of centuries of strife and adversity – they did not come cheap. It is unfortunate that the custodians of religion, the clergy and the schools of religious learning, have not been part of these sensible human achievements. Instead they consider these to be a result of disbelief [in God] and an influence of the West – which is the result of ignorance. That is why we are still witnessing these problems in our country for our Baha’i compatriots.”

Mahnaz Parakand, the human rights lawyer, has taken on cases to defend the Baha’is in the same judicial system run by these jurists. Iran’s Sharia law is, in fact, one of the ways this discrimination is carried out, on top of the taboo created around the Baha’is; but does the treatment of Baha’is have legal roots?

Parakand said the discrimination of the Baha’is has neither a legal nor a judicial basis. “Nowhere in Irans’ criminal code is being a Baha’i a crime – just as being a political activist or a human rights activist is not a crime. And just as being a dervish is not a crime. But all of these groups are dealt with criminally and are treated as security threats. A similar type of case is filed for everyone, namely a security case, by security agencies. The problem goes back to the ideological structure of the state and the constitution and the reliance of the whole system on the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic. This structure has given one person total power, and wherever there is talk of the rights and freedoms of the nation, it is conditional on vague concepts such as Islamic norms. This opens the way for discrimination and disregard of the citizenship rights of the Iranian people. Other parts of society – other than the Baha’is, who are not in this structure – such as Shias who do not accept the Supreme Leader are also subjected to deprivations and restrictions.”

Parakand continued: “I would like to name a few examples of accusations against Baha’is; it is up to listeners and the audience to judge. One of the charges is membership in an illegal group or the ‘errant Baha’i sect,’ with the aim of acting against national security. National security threats range from propaganda against the regime to espionage. There are many cases that open with the same general term and then gradually, during interrogations, grow until one of a charge relating to ‘acting against national security’ is selected and attributed to the accused. Based on my experience, Baha’i gatherings are regarded as gathering and colluding against the regime, for which they are convicted. In all of these charges, it starts with ‘membership in an illegal group,’ or membership of an ‘errant sect,’, and finally, the charge of acting against national security is brought. In the minds of these people all Baha’is are therefore acting against national security.”

October 13, 2021 11:11 am

This is an amazing and remarkable unveiling of slander as a political tool. It is used by this Iranian regime and widely used elsewhere. The damage done to Baha’is is damage done to everyone. Slander tears the fabric of speech, itself. If there is anything to be learned from the mythical Tower Of Babel, it is that when there is no shame for damage done by lies and slander, the very meaning of what it is to be a human endowed with a rational soul, is mocked, trampled. Every divine messenger contended with the lies of those who, from their tower, perverted language by slander. It will not last, but there is a hard road to walk in getting to the truth.

October 14, 2021 9:00 pm

Just a correction to the comment by Dr. Sabeti. It should read as: “Erfan Sabeti said: ‘In the Bible, the Gospel of Mark, we read that Jesus said that a prophet is not without honor except in his own country, among his own relatives and in his own house.'” As it currently appears, it seems to be saying that Jesus told Mark not to be dishonorable, but could be dishonorable in his own country. This is a complete mistranslation of the Bible verse, which is about whether a prophet is honored, not whether the prophet is honorable.

June 8, 2023 5:17 am

The article showcases the dedication and commitment of these individuals to shed light on misconceptions and provide accurate information about the Bahá’í community. It is heartening to see such proactive engagement aimed at fostering understanding and dispelling prejudices. By deconstructing and challenging the narrative, these activists contribute to a more inclusive and enlightened society. This article highlights the power of dialogue and education in dismantling stereotypes and promoting harmony among diverse religious groups.