Source: iranwire.com

Kian Sabeti

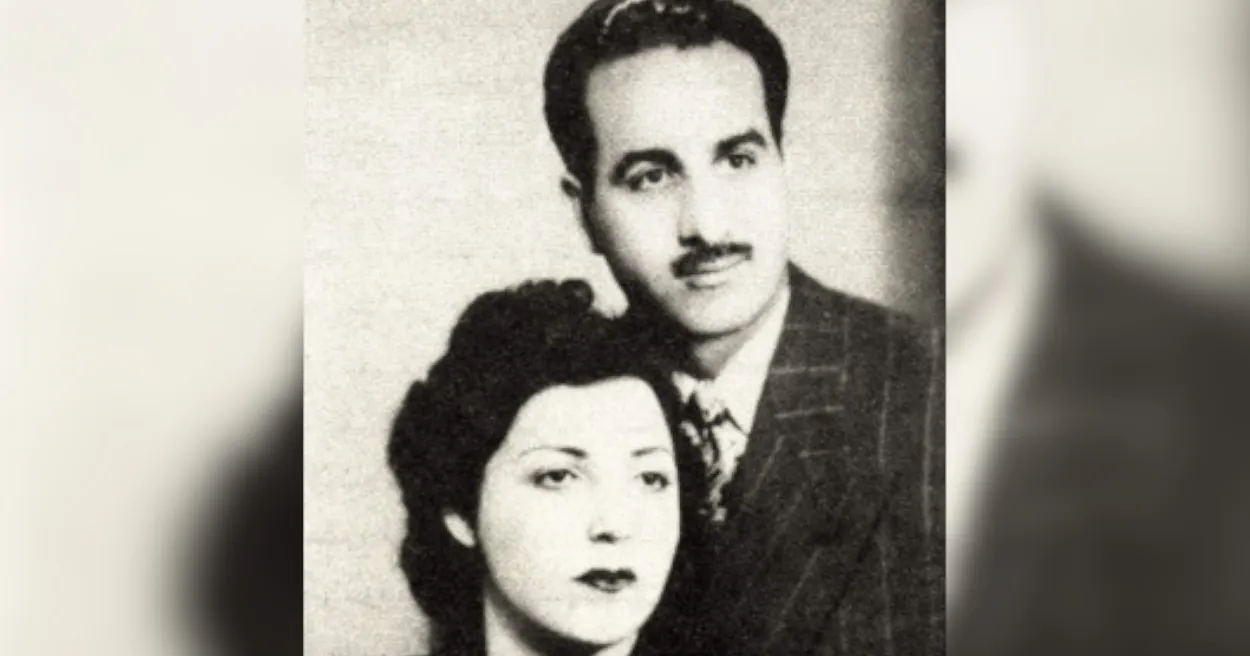

The name Forouhar reminds most Iranians of Dariush Forouhar, the prominent nationalist politician who, with his wife Parvaneh, were assassinated in 1998 in what became known as the Chain Murders of intellectuals and critics of the Islamic Republic. But 16 years before these killings was the murder of an elderly couple with the same surname, Mahmoud Forouhar and his wife Eshraghieh, who were executed because of their religious faith after months of detention without trial and torture.

Mahmoud Forouhar was born in 1917 to a Baha’i family in Abadeh in Fars province. He lost his father as a child, growing up in his mother’s care, and went to high school in Shiraz and Abadan. He also lwarned English and as an adult took a job with the Imperial Bank of Persia.

Eshraghieh Forouhar (née Kambin) was born in 1924 in Tehran to a Baha’i family. Her father, Mirza Shaaban Misaghian, was arrested when he was around 40 years old for teaching the Baha’i faith and. since he testified in writing to being a Baha’i, he was sentenced to prison. Mirza Shaaban’s influential friends later managed to secure his release. But his hardships in prison had damaged his heart and he died in 1928, aged just 42, after spending some months in hospital.

Mirza Shaaban’s wife, Eshraghieh’s mother, became the sole guardian of her five children. The surviving family lived in Tehran for a year and a half and, after her mother remarried, they moved to the city of Tuyserkan in Hamedan province. But they soon returned to Tehran and Eshraghieh graduated from Nourbakhsh High School.

Mahmoud and Eshraghieh married in 1945 and had a child who did not survive. The couple had no other children. Mahmoud was later was hired by Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in Tehran and, while working there, he also received a correspondence degree in accounting from an American university.

Mahmoud retired in 1970 and the couple moved to Gohardasht, then a new borough in Karaj, near Tehran. The Forouhars were the only Baha’is in Gohardasht during their first year – after which Houshang Mahmoudi and his wife Zhinoos moved there and the number of Baha’is in the town gradually increased. Houshang and Zhinoos were among the elected members of National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of Iran and were arrested after the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Retirement for the Forouhar’s was spent in the community on Karaj, for Mahmoud, and for Eshraghieh in teaching women in Karaj and Tehran how to read and write. Eshraghieh visited the elderly and the sick, cared for and cooked for them and even washed their clothes.

But the Forouhars also endured harassment by anti-Baha’i fanatics and well before the outright persecutions of the Revolution. Shia clerics incited locals against the Forouhars and other Baha’is – especially during the holy month of Moharram. Baha’is in the area could hear the profanities directed at them from the loudspeakers of the mosques. But there was nothing they could do.

Threats and attacks against the Baha’is soared after the Revolution. Members of the revolutionary committees attacked their homes, arrested them and confiscated their properties, often without warrants. Many Baha’is escaped and were forced to leave the country. Friends of the Forouhars, living abroad, knew that attacks in Gohardasht and Karaj were increasing and begged Mahmoud and Eshraghieh to leave. But they couple always rejected these entreaties and said they wanted to stay with other Baha’is in Iran who were enduring such difficult conditions.

The revolutionaries raided the Forouhar’s home on August 1, 1981, arrested Mahmoud and took him away. Later they returned to arrest Eshraghieh. When they did, Eshraghieh, who was worried about their small family dog, asked the agents to let her give the dog to someone for safekeeping. One of the agents shot and killed the dog and said: “Now you don’t have to worry about the dog!”

They took Mahmoud Forouhar to a youth center that had been converted into a makeshift prison. Eshraghieh was taken to the women’s prison in Karaj and then to the same center. Mahmoud was later transferred to Ghezel Hesar Prison near Karaj and then returned again to the youth center while Eshraghieh was transferred to a police detention center but then again to the youth center.

Mahmoud and Eshraghieh Forouhar each spent nine months in prison. Mahmoud was 64 and Eshraghieh was 57. Both were tortured as the guards tried to force them to renounce their Baha’i faith and convert to Islam, but despite the beatings, whipping, psychological pressures and solitary confinements, they both refused to recant their faith. And in a further effort to pressure them, Mahmoud and Eshraghieh were told they had been sentenced to death for refusing to convert to Islam and to write their wills; but a few days later, they were told that orders from the religious city of Qom had cancelled the sentenced.

One day, in the final months of their imprisonment and life, the loudspeaker at Ghezel Hesar Prison called out the names of Mahmoud Forouhar and another Baha’i named Badiollah Haghpeikar and said they were to be released. The two gave whatever food and clothing they had to their cellmates and prepared to leave but, instead of being released, they were transferred to a forced labor camp in the prison. When their families first saw them after this transfer, they noticed that Mahmoud and Badiollah were pale, unshaven and disheveled. The pair told their families they had been held in solitary confinement for the previous 10 days and without electricity.

“What crime have they committed that you treat them this way?” a member of Haghpeikar’s family asked a prison official. “They are Baha’is,” the official answered. “If being a Baha’i is a crime then we are Baha’is, too,” said the relative. “If you say one more word, you’ll be arrested as well,” the official said.

Little is known about Eshraghieh’s time in prison. In a letter to Eshraghieh’s sister, Forough Arbab, Zhinoos Mahmoudi, who was imprisoned at the same time, wrote that Eshraghieh had asked the guards for items she did not need but probably wanted to give to her cellmates. The letter, reproduced in the second volume of Shining Stars, a book by Forough Arbab, also said: “Even in the most difficult times [Esharaghieh] has had that lovely emotion: she lived her life for others and did not want anything for herself. I know she is a balm for wounded hearts.”

On May 7, 1982, Mahmoud, now aged 64, and Eshraghieh, aged 58, were executed in Karaj by firing squad after nine months of imprisonment and torment. Badiollah Haghpeikar was executed at the same time. No evidence of trials for any of the three has ever emerged. And the only charge against them was that they were believers in the Baha’i faith: newspaper headlines at the time reported that “Three leaders of the deviant Baha’i sect were executed in Karaj”.

The bodies and wills of Mahmoud and Eshraghieh were turned over to their family and, following Mahmoud’s will, their remains were buried next to each other in Baba Salman Cemetery in Karaj.

A torn note found in the pocket of Mahmoud’s trousers suggest that, when he was writing his will, prison guards took exception to what he had written, confiscated it and tore it up, forcing him to write a different will. Mahmoud apparently put the torn will in his pocket and it was found later by his family. Mahmoud in this note denies the false charges against him and his belief in the Baha’i faith.

The lack of any evidence of a trial means also that the identity of the judge who condemned the Forouhars to death is unknown. But it is clear they were denied access to a lawyer. The Islamic Republic’s own laws stipulate that, if a death sentence had been handed down in a lower court, an appeal could still be made to a higher course and even an upheld verdict would need to be vetted by the Supreme Court. None of these steps were taken in the Forouhar’s case.

But we do know the names of some officials who were responsible for the Forouhars’ case. The first is Ebrahim Raisi, the current president of the Islamic Republic, who was Karaj’s prosecutor at the time. He started his career with the judiciary in 1980 as assistant prosecutor and, a few months later, was appointed prosecutor by Attorney General Ali Ghoddousi. Raisi held this role from 1980 to the summer of 1982 and later for a few months was also the Hamedan prosecutor.

Raisi as prosecutor must have approved the arrest of Mahmoud and Eshraghieh and their transfer to official prisons from detention centers. And the newspaper report of their executions was based on announcements issued by the Karaj prosecutor’s office – by Raisi’s office.

Mehdi Naderifard, who replaced Raisi as Karaj prosecutor in 1982, was also involved in the Forouhar case. Naderifard was close to Raisi and, after Raisi was later appointed Chairman of the General Inspection Office, Naderifard was also transferred there and held various positions in the office. Naderifard and Sheikh Jafar Shojouni also founded the Al Moragheboon group, which held with the same ideology as the Hojjatieh Society, a rabid anti-Baha’i organization that is even opposed to Sunni Islam. Al Moragheboon had defined its mission as identifying and acting against “counter-revolutionary elements”.

Naderifard was also the official responsible for carrying out sentences issued by Karaj Revolutionary Court at the time of the Forouhar’s execution. One published document shows that it was Naderifard who ordered the personal effects of the Forouhars be turned over to their family a few days after their deaths.

A third person connected to the case was Sheikh Mostafa Rahnama, a nephew of Abdolhossein Vahedi, the number two at the Fedayeen of Islam terrorist organization that was responsible for several high-profile assassinations under the Shah.

Rahnama, who was known for harassing the Baha’is before the Revolution, created an armed group after it and used it to attack the homes of the Baha’is in Tehran and Karaj and to seizes their properties by threats and even force. A Baha’i survivor of the 1979 persecutions, Mehraeen Maveddat, whose own husband Houshang was executed, wrote in her book Flame of Tests that it was Rahnama’s group that attacked the Forouhars’ home, arrested them and seized their properties.

Leave a Reply