[Persian BBC, www.bbc.co.uk/persian, 25 Sep 2013]

[Persian BBC, www.bbc.co.uk/persian, 25 Sep 2013]

Sepehr Atefi

Journalist

3 Mehr 1392 (25 September 2013)

31 Shahrivar 1359 (22 September 1980) was the beginning of a bitter chapter in Iran’s history; a chapter that lasted eight years. The suffering and loss caused by the eight-year Iran-Iraq war continues to be felt, 20 years after the end of the war, and for some, may continue for years to come.

In all these years, there have been wide-ranging accounts of the victims, the martyrs, and the leaders and commanders. But amid the clamor of the Islamic Republic’s official media, always sanctifying the war and its martyrs, we notice the inexplicable absence of any mention of the members of religious minorities ̶ who also fought and were killed or taken prisoner ̶ in any documentary, TV series, movie or book.

As one example, since the Revolution Baha’is in Iran have been constantly subjected to discrimination and persecution on a daily basis. Observing the events of the last 34 years, it is clear that whenever the regime found itself facing internal or external crises the pressure on Baha’is increased considerably.

Status of Baha’is during the war

During the initial years of the revolution, before conflicts among the various revolutionary factions emerged, Baha’is were persecuted under various pretexts. For instance, on 30 Mordad 1359 (21 August 1980), one month before the outbreak of war, members of the administrative body of the Baha’i community were kidnapped, and then disappeared without a trace.

According to Fereydoun Vahman, author of “160 Years of Persecution of the Baha’is of Iran”*, “The eight-year war was a golden opportunity for opponents of the Baha’i Faith to continue the persecution and execution of Baha’is which had started at the beginning of the revolution. During this period, any criminal activity – let alone persecuting Baha’is – could be justified as fighting Saddam. During the war years no authority was held accountable for the suffering and injustices perpetrated on Baha’i citizens.”

Regarding the number of Baha’is killed during the eight years of the war, and the lack of accurate statistics on the number of Baha’i casualties and prisoners of war, he adds: “During the presidency of Abolhassan Banisadr, 56 Baha’is were jailed; during the one-month presidency of Mohammad Ali Rejai and prime minister Mohammad Javad Bahonar, 12; during the one month that Mohammad Reza Mahdavi Kani served as prime minister, 5; and during the presidency of Ayatollah Khamenei and prime minister Mir Hossein Moussavi, 119 were jailed, subjected to the most heinous torture and executed. Yet, so far, no government authority has been answerable for this injustice and tyranny.”

In addition to being persecuted and executed, during this period Baha’is were also expelled from government and academic jobs; Baha’i weddings were decreed illegal and Baha’i children were considered illegitimate by the legal system.

Baha’is and War

“Taking up arms is against our faith.” By voicing their beliefs Baha’i soldiers hoped to serve in administrative or non-military capacities. That is what Gholamreza Alai, a Baha’i citizen, requested of his commanding officer. His brother, Zeinalabedin Alai, recalls what he told his family: “It is true that we’re against war, but maybe if they learn that I am a Baha’i they will not send me to the front line.” Mr. Alai adds: “But the opposite happened. When they found out that he was a Baha’i, they told him he had to go to the front.” Four months after being sent to the front lines and shortly after he turned 20, he was hit and killed by a grenade. The reaction was not always negative. Bahman, who enlisted in the army in Tir 1365 (June 1986) and spent 25 of his 28-month stint in the war zone says: “Generally speaking, I must say I was treated well. They agreed to let me serve where I requested to go. But reactions were not the same everywhere.”

Baha’i POWs, anxiety and lack of communication

Jamshid decided to enlist when he was 19. Six months later, on 17 Shahrivar 1359 (8 September 1980), having been recently assigned to the Khan Leili station on the Iran-Iraq border, and a few days before the actual beginning of the war, he was taken prisoner during an incursion by Iraqi forces. He was released 10 years later, at the end of the war. Jamshid says: “On my enlistment form I had indicated that I was a Baha’i. But after being captured no one – including the Iraqi army – was interested in my religion.” He continues, “For 10 years I had no information on the situation in Iran. Our letters to our families would take a year to reach them and were censored by both the Iranians and Iraqis.” He points out that after the arrival of the new prisoners the atmosphere in the dormitory became pro Hezbollah and pro-clergy. “Each dormitory held 70-100 prisoners and each of us had approximately a 40-cm-square area to ourselves. Two prisoners who were encouraged by the Hezbollah group to escape were caught under the barbed wire fence. After that the conditions became much harder for the rest of the prisoners. Two sets of large windows on either side were closed up so that we could not tell day from night. They reopened one of them after a year or two. These were hardships caused by some of the Iranians. No one dared confront them; if someone had done so, no one in the prison would ever have spoken with them again.” These adverse conditions were of course shared by all the prisoners, but for Jamshid “being a Baha’i” was the cause of greater discrimination.

How did Baha’i and other non-Muslim prisoners cope under these conditions? “No one knew me there. I tried to stay neutral. I neither associated with the Hezbollah group nor befriended the Iraqi prison guards and soldiers. I was afraid – of the Iranians as well as the Iraqis. I conducted my daily devotions secretly. During Friday prayers I would stand in the back row and recite my prayers. Sometimes, when I was assigned to clean the dormitory, I would sit in a corner by myself and say my prayers after everyone had left.”

Discrimination, prisoners and unrecognized martyrs

Discrimination, prisoners and unrecognized martyrs

Zeinalabedin Alai states that after his brother was killed, Bonyad Shahid (Martyr’s Foundation) archived his file and the person in charge called Baha’is perverted and a deviant cult (fergheh zalleh).

“They said they archived his file because they were not certain that he was martyred and that he may have committed suicide. I told them that they should show some compassion and sympathy instead of treating us this way. I said that if we are perverse, you should show us the right path. After a lengthy discussion they apologized and told me they would do what they could to assist us.”

Mr. Alai adds that their situation was not similar to those who had lost a child or a spouse; nonetheless he and his family did everything in their power to claim their rights.

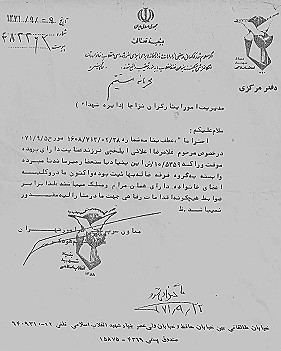

“In court, after my numerous appeals, the judge said he regretted the turn of events and showed me a letter stamped “confidential” which stated that they must refrain from providing written replies to the members of the “deviant Baha’i cult”, as any written document would legitimize their existence.” He continued, “Since the Martyr’s Foundation had archived the file and would not respond to our inquiries, we appealed through Army channels.”

The Army kept inquiring about the status of these individuals. The latest ruling they received from the Leader [Ayatollah Khomeini} was that the pensions of Baha’is killed in action should be paid.” Mr. Alai says that his mother’s pension was reinstated after ten years of appeals.

Jamshid also states: “We were under the jurisdiction of the Azadegan Regiment. Their form included a section for religion. I put Baha’i as my religion. Our commander was an unbiased man. He said Central Command had announced that all non-Muslim applicants should be removed from the list and their files closed, but since he had not received anything in writing, he would disregard it.” He adds that the support gradually diminished. Later, he was told that if he put down Muslim as his religion he could go straight to university and could get a government job. Jamshid says, “Generally, those who adhered to the regime’s policies were taken care of but those who didn’t suffered many injustices and discrimination.”

Of course, discrimination toward the survivors of the martyrs and prisoners of war was not limited to Baha’is alone. All other groups who were forced to fight, or those who did not consider the war to be “a war between right and wrong”, as Ayatollah Khomeini put it, were sacrificed during the eight-year Iran-Iraq war.

—

Translation by Iran Press Watch

Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/persian/iran/2013/09/130924_l44_iran_iraq_war_bahai.shtml

* Available (in Persian) here: http://www.bahaibookstore.com/productdetails.cfm?sku=P160YR#.UkT2vH_gxMg

Leave a Reply