Source: iranwire.com

Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iranians were either ecstatic or silent. Their charismatic leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, had won a revolution that they thought would bring them sunshine and roses. The excitement was such that red flags that manifested themselves early on were either unnoticed or dismissed.

Individuals who had seen past the charisma – and seen through Khomeini and the system he was putting in place – were slowly wiped out. Any group that posed an ideological or political threat, such as religious and ethnic minorities, were targeted and their rights were violated. The reaction from the public at the time was either silence or satisfaction.

Such an environment was to the advantage of the new Islamic Republic regime, which continued its extrajudicial killings, arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, torture and destruction of properties with even more zeal. The aim was to marginalize all minorities as part of a state-led effort to cleansing Iran of any non-Islamic “impurities”.

Targeting minorities and opposition groups was the Islamic Republic’s way of testing the waters. Support from Iranian society over such violations, and the deafening silence of the international community over human rights violations against various minority groups in Iran, only strengthened the regime and prepared the ground for the growth of a seedling that has turned into a monstrous tree that embodies violence, victimization, and offence over the four decades of rule.

Once these violations became too great to ignore, the international community and Iranians began to question the Islamic Republic and their so-called “supreme leader”. But by then the Iranian regime had become strong enough to lie about its actions in Iran – including its violations of the human rights of minority groups. Iran at first denied them, and the international community was content with having just received a response; however, because Iran felt no consequences for its actions, its violations became more egregious, prompting fresh pressure from the international community. But observers, NGOs and others began to see more clearly the evidence before their eyes, and the Islamic Republic’s true nature became more and more clear. The regime, in turn, began experimenting with various tactics to distract the world and society. It began scapegoating, pointing fingers, and blaming minorities (the victims) for the violations that were taking place. It continued to “other” minorities and to create non-existent “enemies” of the regime.

The Islamic Republic has become more and more entrenched over the years, and its power has grown, even as discontent has also swelled in particular since the 2009 presidenital election widely thought to have been rigged in favor of the regime’s candidate. And the circle of those innocent Iranians whose rights have been violated has become wider and wider, until it became so wide, so encompassing, that the death of one, the young Mahsa Amini, out of so many before her, triggered a nationwide explosion of demonstration and unrest.

Iran’s recent protests in Iran – and the people’s struggle to chop down the monstrous tree that is the Islamic Republic – would have been far easier had it been dealt with earlier by a country that had chosen to protect its minorities and to bring perpetrators to account for even just one wrongful death, imprisonment or seizure.

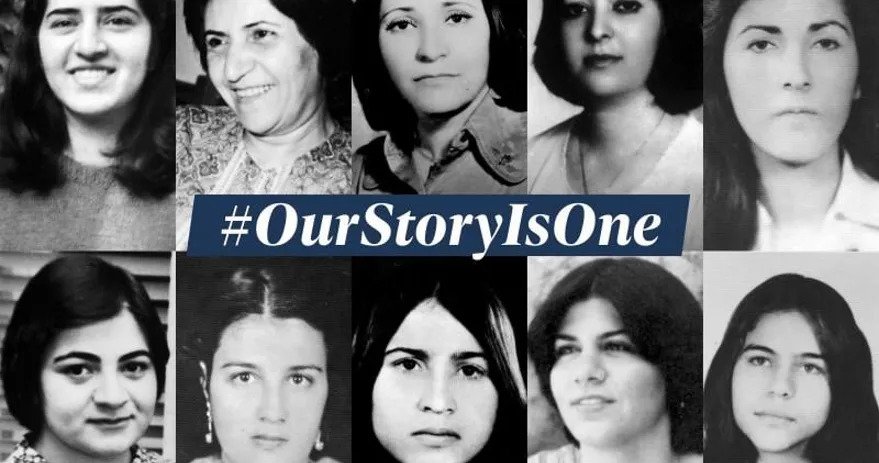

Forty years ago, on June 18, 1983, the Islamic Republic of Iran hanged 10 Baha’i women in a single night in Shiraz. The women were killed because they refused to recant their beliefs in the Baha’i Faith, an independent world religion that promotes the principles of gender equality, unity in diversity, justice, and, as the foundation of all human virtues, truthfulness. The Islamic Republic remained standing after these executions even though there was an international outcry. The lack of serious consequences to the regime and those in its system, after the deaths of these women, only fuelled the Islamic Republic’s fire and emboldened it, just like many other wrongful deaths, killings and executions before and after.

Decades of entrenchment by the Islamic Republic means that Iranian society now finds it difficult to uproot it – or to ensure that its perpetrators are brought to justice after more than 40 years of human rights violations. But what can make it easier, for all Iranians, is to realize more and more than our story is one.

Our story became the same the moment one of us was unjustly killed; because ultimately, as Iran’s history illustrates, the violation of the rights of one becomes a violation against all. The names or the identities of the violation all become the same: in 40 years Iran has gone from the hanging of 10 Baha’i women with little to no reaction inside Iran to the murder of Mahsa Amini provoking nationwide and international protest.

The blood of these 10 executed Baha’i women, in 1983, shows that the blood of these women and many others have not been shed in vain. People are reaching the realization that we are all one, and that we can only stand up to injustice together, and that it must be today. Human beings cannot afford to wait for human rights violations to affect us too before we decide they are wrong – any later is too late.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” — Dr. Martin Luther King, 1963

But the next step is for us to internalize the fact that standing up to human rights violations ought to be a conscious and values-based decision – instead of just responding to the fear that next they may come for us.

Leave a Reply