Source: iranwire.com

Kian Sabeti

“Tonight I come from Adelabad Prison, the home of free spirits and butterflies who have been consumed by the flames of affection; where inside its high and stony walls spirits greater than its walls are in chains; where each stone cries out in amazement, amazed by nameless heroes whose silent screams pierce the high walls of the dungeons of the tyrants and one day shall pierce the dreams of the wicked and shall awaken the world. I wish to ask these walls: what have you seen? Tell me about the songs of self-sacrifice, of the last beatings of the heart of a lover as he draws near his death. Tell me what they said when they rushed to their martyrdoms. Talk to me of whispered prayers that you hear at dawn, from behind bars, and of the teardrops that fall from their eyes.”

So wrote Zarrin Moghimi-Abyaneh after visiting a prisoner of conscience at Adelabad Prison in Shiraz. Later she herself was arrested and hanged for being a Baha’i.

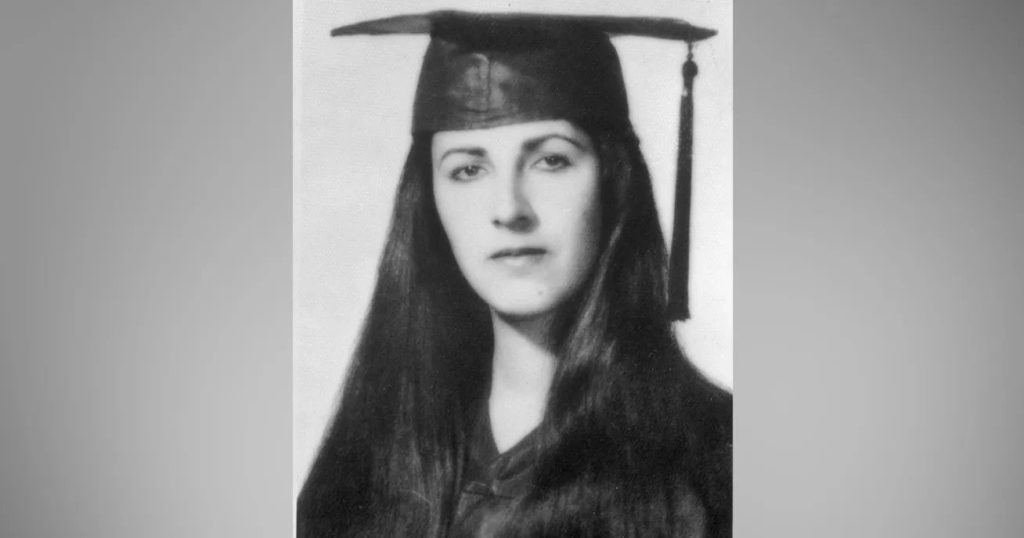

Who Was Zarrin Moghimi-Abyaneh?

Zarrin Moghimi-Abyaneh was born on August 23, 1954, in the village of Abyaneh in the Central District of Natanz County, Isfahan Province. She was the third and youngest child of Hossein Moghimi and Ummehani Salehi. Her father came from a Baha’i family but her mother converted to the Baha’i faith a few years after they were married and before Zarrin was born.

The family moved to Tehran shortly after Zarrin’s birth. Zarrin completed her schooling there and then studied English literature at Tehran University where she received her bachelor’s degree at 21 years of age.

Zarrin moved back to Abyaneh after graduating from university. Though she was still young when her family left the village, she loved her birthplace and wanted a chance to return there and to serve its people. But she was refused a job in the village because of her Baha’i faith and so rejoined her family – who were now living in Shiraz.

Zarrin’s father, meanwhile, Hossein Moghimi, was one of the best-known stucco masters in Iran. An example of his work can be seen in Marmar Palace in Tehran which is now an art museum. In 1972, he was sent by the Baha’i community of Iran to Shiraz to repair the home of Bab, founder of the Babi faith which was a forerunner to the Baha’i religion, and as such a central figure of the Baha’i faith.

Life in Shiraz

Zarrin was hired by the Shiraz Petrochemical Company as a translator and treasurer. She lived with her parents in a house in Shamshirgaran Alley. Her brother and sister had left Iran to study abroad.

Most people in the neighborhood were poor. Zarrin always viewed and treated them with kindness and with a tender heart. And when her father suggested that they buy a car for her, she refused, saying “I want to be like other young people in the neighborhood. I don’t want them to feel that we are apart and that I have something more.”

From the 1979 Islamic Revolution to Arrest

With the establishment of the Islamic Republic, in 1979, Baha’is were subjected to harassment and persecution by the government. The Moghimi family was no exception. Baha’i religious sites, including the home of Bab in Shiraz, were seized. Arrests and executions of Baha’is started in Shiraz as well and, from 1980 to 1981, five prominent Baha’i figures in the city were executed.

The situation alarmed relatives of Baha’is who lived outside Iran. Simin, Zarrin’s sister, called from abroad and advised her to leave the country. “Don’t say this,” Zarrin replied. “Much needs to be done but time is short and there is not enough manpower. Whatever happens to other Baha’is will happen to me as well. My life is not more valuable that their lives. I will never leave this country.”

Until her arrest, Zarrin spent her time teaching Baha’i children and teenagers, giving comfort to the families of those Baha’is who had been imprisoned or executed, and helping others who had lost their homes or been displaced. The dispossessed fell into two groups; those who were driven from their homes in by Iraq’s invasion of Iran, and those who had been driven from their homes which were then destroyed by local zealots during the Revolution.

Zarrin’s and Her Parents’ Arrests

In a coordinated and simultaneous operation on the evening of October 23, 1981, forces of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) raided a large number of of Baha’i homes in Shiraz and arrested 38 people. Without presenting any search warrants, the IRGC officers entered these homes and, after conducting searches and confiscating religious books and pictures and prayer tapes, they insulted and ridiculed the detained Baha’is and took them to the IRGC detention center in Shiraz.

Hossein Moghimi, his wife Ummehani Salehi and their daughter Zarrin, who by this time was 28, were among the detainees. The agents had warrants only for the arrest of Hossein and Zarrin; but after Zarrin’s mother insisted that she could not be separated from her family, she was also arrested.

The IRGC interrogators wanted to force the Baha’is to recant their faith and to convert to Islam – while also gaining more information about the Baha’i believers and the activities of the community. They used every method to get what they wanted, from insults, humiliation and ridicule, to beatings. The detainees were forbidden to pray so were forced to recite their prayers silently, at night, when other prisoners were asleep, so that they would escape notice.

Zarrin was well-versed in both the Baha’i religion and Islam and, as a result, her interrogations lasted a long time because of the efforts by interrogators to convince Zarrin to recant her faith. Her cellmates later remembered that once, when her interrogator had failed to win an argument, they brought in a few people from outside the prison to try prove her wrong.

The Hearings and the Trial

On the evening of November 29, 1982, the Baha’i prisoners were transferred from the IRGC’s detention center to Adelabad Prison in Shiraz. The agents then arrested 40 more Baha’is in Shiraz, an hour later, and took them to the detention center.

All the detainees were charged with the so-called crime of being Baha’is. The questioning at Adelabad was not as violent as at detention center; but they still pressured the Baha’is to renounce their faith, and to convert to Islam. Assistant prosecutors told the detainees that they would be released if they repented – otherwise that they should expect the death sentence. But none of these threats and promises had any effect on Zarrin and her cellmates.

Trials for the Baha’is began after their hearings. All the sessions were held in the same way. The defendants were each tried in just a few minutes, without a lawyer, and at the end of the trial session, Hojatoleslam Ghazaei, the Sharia judge of Shiraz, told the defendants that had only two options; Islam or execution.

Death Sentences

In February 1983, the newspaper Khabar Jonoub reported that the Shiraz Revolutionary Court had sentenced 22 Baha’is to death. The Baha’is were not named. The news was not official – it had been leaked – but when on February 22 the newspaper’s reporter asked Judge Ghazaei about the case he implicitly confirmed the sentences. “The Iranian nation has risen up, based on the Quran and according to divine will, and it cannot tolerate the Baha’is,” Ghazaei said.

On February 23, the prosecutor met with all the Baha’i prisoners, men and women, and gave them an ultimatum. He said that they had been sentenced to death and that the decisions had been upheld by the Supreme Judiciary Council – but that he had not yet signed them. He told them that if anybody converted to Islam they would be released; otherwise, the death sentence would be carried out.

Zarrin Meets Her Father in Prison

After the arrest of all three members of the Moghimi family, they were not allowed any visitors until Zarrin’s mother was released in January. She was then the person allowed to visit her daughter and her husband, once a week, separately and from behind a glass partition.

Zarrin and her father met in prison just one time – just after the prosecutor’s ultimatum “I embraced Zarrin, and then she put her hands on my shoulders, and said: ‘Stand firm, father! Stand firm so that I can be proud of you,’” Hossein Moghimi said later.

The Execution of Tuba Zaerpour

One of Zarrin’s most painful days was the execution of her cellmate, Tuba Zaerpour, with whom she had shared Cell 18 since being jailed. Tuba was like a mother to Zarrin. She was a high school teacher of Arabic language and literature in Shiraz. On March 12, 1983, after seeing her family for a last time, she was hanged along with two Baha’i men. Tuba Zaerpour was 51 years old at the time her of death.

Repent or Die

By the order of the prosecutor, each Baha’i had to repent four times. If they refused, they were executed or, as the authorities put it, the “divine verdict” was carried out. Zarrin was the second prisoner from the women’s ward who was taken to repent. On June 13, 1983, she was summoned four times, each time half an hour apart, to repent; each time Zarrin wrote, “I am a Baha’i.”

The fourth time that Zarrin left the room, she asked Torabpour, the chief warden: “Where should I go for execution?” Torabpour replied: “It is not so simple. We must ask Tehran for confirmation. For the moment, go back to your cell.”

Five days later, on Saturday, June 18, an hour after weekly visits, Zarrin Moghimi and nine other Baha’i women were taken from Adelabad Prison to Abdollah Mesgar Barracks, previously known as the Polo Arena, and were hanged in front of each other. The prosecutor did not allow any of them to write a will. The Revolutionary Guards buried their bodies without the presence of their families and without religious rites. The youngest of these Baha’is was 17, the famed Mona Mahmudnizhad, and the oldest was 57 years old. Zarrin Moghimi was 29 years of age.

Zarrin owned no property: she had a saved some money which was confiscated by the Revolutionary Court after her execution. The Moghimi family’s home was later also confiscated and Zarrin’s mother was driven out.

Zarrin’s father, Hossein Moghimi, was released from Adelabad Prison in the late summer of 1984 after 22 months in prison.

Author’s note: A major portion of this report comes from an interview by the author with Zarrin Moghimi’s brother.

Leave a Reply