Source: observer.com

Violence aimed at minority cemeteries is a disturbing call for ethnic purification

Recent attacks on Jewish cemeteries and religious centers in the United States is shoring up the darkest of my elegiac memories.

As an Iranian-Norwegian girl who carried the Norwegian flag to our neighborhood’s Protestant church on high holidays ahead of a gaggle of tall Norwegian sixth graders, I was informed by the mournful history of Shi’ism and its defeat against the Sunni caliphate, which animates my bloodline, regardless of my birth into a Bahá’í family. As Bahá’ís my family believed in the unity of all religions and the oneness of God. Happily, even in Norway, we saw ourselves as citizens of the world.

In my teens, I spent my Saturdays just like many Jewish kids preparing for their bat mitzvahs—in study circles, reading the Bahá’í writings and memorizing the sacred texts. There were no priests or rabbis. Bahá’í’s don’t have a clerical class, but the two older boys whose home I would visit on these Saturdays kept our discussions lively—and my heart atwitter. They were brothers who had just moved to my hometown of Oslo from the far North to continue their university studies in the capital. At 19, one of them had me at “hello.” He was tall, blue-eyed and could speak with authority on virtually every topic. In his presence, I could see myself as a café-going French intellectual. There was no reality to that, though. Dark-haired and olive-skinned, I had a massive unibrow and steel braces. There was nothing sophisticated about me.

It was the early eighties. The 1979 Iranian revolution had ushered in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The new constitution refused to recognize the Bahá’ís among the other Iranian minorities, Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, and the new government insisted, by law, that Bahá’í blood was mobah—meaning Bahá’ís were unprotected and could be killed with impunity. My family’s properties and businesses were confiscated in the course of this violent transition. Those closest to us were imprisoned and executed because of their faith. We couldn’t realistically return home from Norway.

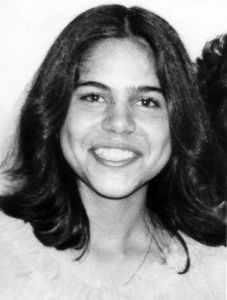

Muna’s picture, with beautiful dimples brightening her smile, haunted me from the bookshelves that decked the entire west wall of our study circle. My attention drifting from the Holy texts as I wondered if that could have been me had my family stayed in Iran.That summer, the summer of 1983, when the Northern boys moved into my now exilic life in Oslo, a series of executions took place in the city of my mother’s birth, Shiraz. Among them was a 17-year-old Bahá’í teacher, Muna Mahmudnizhad, who was said to have joyfully kissed the executioner’s noose before putting it around her own neck. Despite months of imprisonment and torture, she was not willing to recant her faith as a Bahá’í, deny her humanity or give up the ties that bound her to a vision of herself as world citizen.

Seventeen years later, in 2000, my mom eventually went back to visit her aging father in Iran. Arriving at Mehrabad airport, my mother was stopped and her passport was confiscated. For the next three months she was called in for questioning every day. In a chair across from hers, the officer would carefully dress his seat with the most sacred symbol of the Bahá’í Faith—the Most Holy Name—sit down on it, and commence a series of daily-repeating inquiries regarding her circles, her friends, the processes and whereabouts of Bahá’í gatherings, her take on the Bahá’í writings, her family, her children, and her work. It was a study circle of sorts, I guess. Hours of precious time she could have spent with my grandfather were wasted like this, until one day, the officer handed her her passport, and with no further explanation about why she had been detained, told her to leave Iran—her own country—and to do so immediately.

There would have been nothing joyful or accommodating about my demeanor had I been the subject of this three-month examination of faith and extreme vetting. This kind of questioning, of passports and digital networks on travelers’ phones and laptops, is already happening at ports of entry in the United States. Many of us—without the patience, understanding, and forbearance demonstrated by my mother in the face of disrespect, virulent prejudice and expressions of authoritarian power—are destined to fail that test.

A little over two years ago, the Bahá’í cemetery in my mother’s hometown of Shiraz was excavated by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. The tombstones were leveled, and nearly 1,000 Bahá’í graves exhumed. Muna’s was one of the bodies buried there after she kissed the noose. The Revolutionary Guard said it was razing the cemetery to build a new cultural center.

The desecration of the cemetery is an unequivocal gesture of the erasure of the ties that bind—ties to our memories, our traditions, to history and culture. When violence and destruction are aimed at cemeteries belonging to national minorities—such as those of the Jewish communities in the United States and the Bahá’í community in Iran—it is also a call for national purification, a nationalist project.

Neither the ties that bind us to our networks—those showing up in our lives online—nor the ties that bind us to our cultural past—those in our cemeteries—are ties that neatly fit the project of nationalism. Nationalism at its root is arbitrary: constructions based in prejudice, separation and violence.

Today, so much of the vetting and severing of our ties is done in the name of American nationalism. So, I wonder, given all that binds us to a world here and beyond, how could we possibly—we, a global humanity, born to one earth and under one sky—ever be ok with any of this?

Negar Mottahedeh is a professor of film and media studies in the Program in Literature at Duke University. Her most recent book about citizenship and civic engagement during the Iranian post-election crisis of 2009 is called #iranelection: Hashtag Solidarity and the Transformation of Online Life (Stanford University Press, 2015).