By Nasrin Almasi

Source: shahrvand.com

Translation by Iran Press Watch

I have been following the issues related to my Baha’i compatriots for years, and consider myself more or less aware of the magnitude of the systematic persecutions meted out against this community by the fundamentalist authorities and the fanatics in Iran. And yet, Mehraeen Mavaddat’s memoir, Flame of Tests, is shocking.The reason is clear: the book is based on real memories of real people; memories that immerse us in shame. While reading this book, the question repeatedly came to my mind—is it possible that in the 21st century (not the Stone Age or the Middle Ages) a group in the guise of humanity, motivated by ignorance and prejudice, could commit such acts –no less in the name of us Iranians?

I sat down with Mrs. Mehraeen Mottahedin (Mavaddat) to discuss her book, Flame of Tests: The Story of Farhang Mavaddat. She was born to a Baha’i family. On her mother’s side, she was the fifth generation descendent of Agha Jan, the first Baha’i of Jewish background in Hamadan, a city which was a center of the Iranian Jewish community. On meeting and marrying her husband Farhang Mavaddat, she sweetly recalls:

I was not planning to get married. I was a studious girl and my parents also wanted me to continue my studies, but when I was in the 11th grade, Farhang, through one of our neighbors, asked for my hand in marriage. My mother became enamored of Farhang’s character and before I knew it, arrangements were made for the marriage. Farhang was a chemical engineer, and at the time worked at the sugar factory in Rezaieh. Once the marriage was arranged, he returned to Rezaieh and during this time we became further acquainted through correspondence. When, in the summer, he came back for the wedding, my mother suggested we should get to know each other better before marrying. Honestly, until then, if I saw him on the street, I wouldn’t recognize him – because I was a shy girl and even when he came to ask for my hand, I didn’t get a good look at him!

We were supposed to get married in Mordad 1332 (August 1953). At that time, there were demonstrations in the streets. I guess, my whole life was meant to be filled with turmoil and revolution. This was right in the middle of all the unrests, the coup and the martial law. Never having been involved in politics, we were terrified of what would happen. As I never liked extravagance, I made myself a simple wedding dress and we were supposed to get married on the 29th of Mordad (20th of August). Due to the martial law, we were not permitted to get married in a public hall. So, the next day, we were married in a very small private ceremony, before the hour of curfew, and a week later, together with my husband, whom I was supposed to get to know later, left for Rezaieh. Imagine my anxiety, a 16 or 17-year-old girl, living in a strange city, where she doesn’t know the language and has no friends, classmates or family around. I had gone from the comfort of my father’s luxury home to a simple and modest life in a remote place. It difficult to adapt myself to the new conditions but I was committed to my marriage and family. Since the sugar factories were usually built outside of cities, we were far away from town and the solitude and isolation was new to me. Farhang was either working or studying. I had taken my books with me so, I got my high school diploma, and had three children one after the other. Due to Farhang’s job, we moved from town to town and factory to factory. In fact, because of Farhang’s good work ethics and expertise in his field, he was assigned to fix any factory that lacked productivity or had issues. It was really his love for knowledge, his scholarly character and his work ethics that won my heart. I have always felt that there were no engineers in Iran with more expertise and knowledge than Farhang. He was always taking college courses or studying books he would order from abroad and he had great ideas about the progress of the sugar industry in Iran. He was always thinking of ways to improve industries and mining, for the country’s progress. Being a Baha’i prevented him from being recognized and compensated for the work and energy he spent in this area. In spite of this we made a living and thrived.

You were not satisfied with just the high school diploma, correct?

Yes. After many years when our children were grown, at Farhang’s suggestion, who knew my love for studying, I took the university entrance exam. Fortunately, I was accepted the first year, and was among the top students. In the mornings, the children and I would go to school and university and return in the afternoon. Originally, I was going to take a few units so I could manage the load but I was quite determined and able to graduate in four years.

I got a job as a legal analyst and worked my way up. I loved my work environment and my coworkers; they helped me in my time of need. After the revolution, my boss was promoted to Iran’s Minister of Customs. Despite being a Muslim and a devout person, since he had studied law, he did not agree with the ways of the Islamic Republic, and said one’s religion has nothing to do with one’s profession and expertise. Due to my position and role in that office, everyone tried to prevent my case as a Baha’i from coming up, so I would not be subject to “cleansing” following the revolution.

In what year were you fired?

I was never fired. My boss eventually admitted that he could no longer protect me and suggested I take a year of unpaid leave, so I did. Of course, things got so bad I had to leave Iran.

In your book, you describe how Baha’is have long been victims of oppression and injustice, that, in fact, the Society for Propagation of Islam had devised plans to eradicate the Baha’is years ago. What kind of an organization was the Society for Propagation of Islam, and what kind of activities did it engage in?

You have surely heard the name of Hojjatieh Society, which was established by some prominent and fanatical Muslims. The Hojjatieh Society’s mission was to eradicate the Baha’is. They had plans and programs. Before the Revolution, whatever gathering or meeting we had, two or three of them would show up to harass us, interfere and disrupt the meetings. We always had to meet discretely, not to attract their attention. Some of them had falsely registered as Baha’is. As you know, we Baha’is have to choose our religion at the age 15—no one is born into the faith. So at age 15, a person will declare their belief in the Baha’i Faith. From then on the person is considered a member of community and is issued an identification card. This is how the Hojjatieh Society was able to get access to the Baha’i declaration cards and steal identities. In Karaj, a few of these people had infiltrated our community and our administration with the purpose of sabotage. During the months of Safar and Moharram, it was nothing but insults and hatred towards us. Even though my daughter was enrolled in a private school, hoping to avoid prejudice to some degree, still children in her school would tear up her books and call her a Baha’i Dog!

What is the role of assemblies in the administration of the affairs of the Baha’is? Essentially, how does the Baha’i community carry out its affairs? What hierarchy exists in your religion?

In the Baha’i Faith, we don’t have clergy or leaders. Baha’u’llah wanted to establish a spiritual civilization based on consultation and election, a form of democracy and freedom. Every Ridvan, which is on April 21, must elect nine people from among them, over the age of twenty-one, by secret ballot. These nine people will become members of the assembly and will elect a chairman and a secretary from among themselves and handle all matters by consultation. Things such as forming children’s classes, establishing feasts and gatherings, matters of marriage and divorce, burial and so on are all handled by the assemblies. In addition, the assemblies are responsible for looking after a family if they have financial needs, and all these services are provided free of charge and voluntarily (members do not enjoy any additional privileges). This body of nine is a local assembly.

Once a year, delegates from each area (based on the population) come together in a gathering and elect members to the National Assembly in all countries. At present we have 300 National Assemblies, whose responsibility it is to oversee the local assemblies. If local assemblies have problems they cannot solve, the National Assemblies take over. Furthermore, once every five years, these National Assemblies gather in Haifa, the seat of the Universal House of Justice (the international governing council of our religion). By secret ballot they elect the members of the Universal House of Justice, whose responsibilities include overseeing the National Assemblies throughout the world.

Why is the Universal House of Justice located in Israel when your prophet was born in Iran?

Firstly, the state of Israel was created much later. When our prophet (the Bab) was killed in Iran, Baha’u’llah was sent into exile. First to Iraq, then to Adrianople in Turkey, then to Istanbul, and finally to the worst spot on earth, that is Akka, which was a barren and desolate place with terrible climate. There was a saying that the air was so foul in Akka that a bird flying over it would fall from the sky and die! Baha’u’llah was exiled there during the Ottomon rule, when the state of Israel did not even exist yet. He was sent there because they believed no one could survive in that place and as such, the Baha’is would be destroyed. Baha’u’llah was a prisoner for 40 years in Akka. In fact, he passed away there, and was buried there. Afterwards, the remains of the Bab, who had been killed in Iran, were also transferred there. The Bahai World Center was built in Akka to honor our founder and prophet and for this reason, Akka is a holy place for us.

Tell us about the events in Shiraz. In what year was it and what occurred? Did similar events happen in other places as well?

It was in Mordad 1358 (August 1979). Since there were many Baha’is in Shiraz, they attacked them and burned down their homes, and those poor people had to flee on foot in the middle of the night. Many of them sought refuge in our homes, and clothing and money was collected for them. Then the House of the Bab in Shiraz was confiscated and destroyed. Obviously, this was a grave insult to us Baha’is and very painful. This was a holy place to us. Imagine if Mecca was destroyed, how would the Muslims feel? Or if the holy places of other religions were destroyed?

In the face of such events, what did the Baha’is do individually or collectively, as a group? Did they complain to the authorities? What was their response?

We weren’t silent. We filed complaints with the authorities, but they didn’t necessary care.

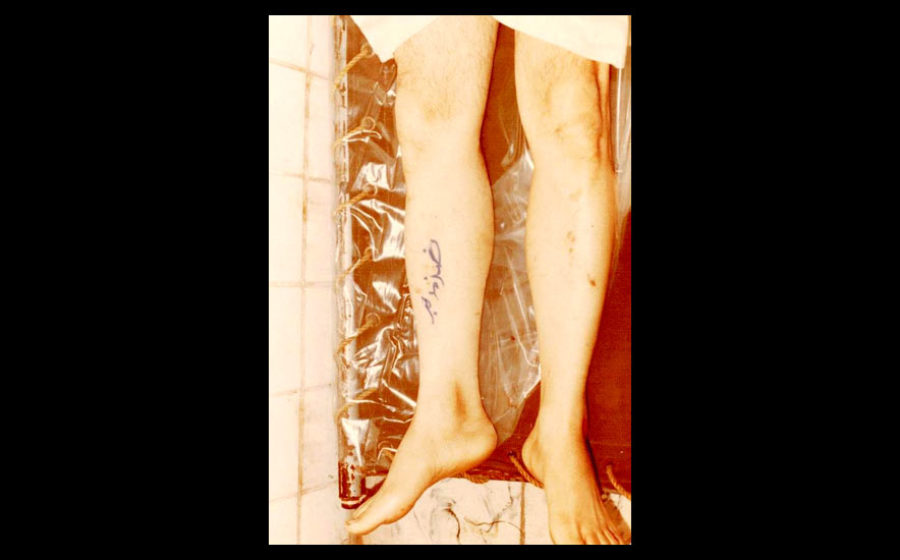

We were also instructed by the Universal House of Justice to contact representatives of the Islamic Republic of Iran in all the countries, and ask them to be responsible and accountable for the plight of the Baha’is. We were advised to write them and ask what crime or transgression the Baha’is were being harassed and killed for, why their properties were being confiscated and their children deprived of education. Those letters were written but they fell on deaf ears. No one ever responded, and they denied such persecutions were taking place. As they say, a liar has a short memory – on the body of my husband, who was executed, his name was written on his chest. On his legs they wrote, “anti-religion.”

Do you have statistics of the abduction of Baha’is? What did the families do in those cases?

We have tried to compile the statistics on all those who were detained, abducted and killed.

At the beginning, they would detain Baha’is individually, but then they raided the assembly meeting and detained the assembly members as a group. Dr. Davoudi, who was a professor of philosophy, and much loved and very knowledgeable, and a former member of the National Spiritual Assembly, was abducted. The secretary of the Tehran Assembly, Ruhi Rowshani was abducted on his way to work and we still don’t know his whereabouts, or whether he is dead or alive. Mr. Movahed, a former clergy who had become a Baha’i, a very nice and knowledgeable young man, was abducted, and despite his pregnant wife’s many attempts to inquire of his fate, no trace of him was found.

On 31 Mordad 59 (22 August 1980), during a raid, nine members of the assembly and two counsellors were detained, which was a heavy blow to the Baha’i community.

We were advised not to stay in our homes, especially because Farhang was a member of the assembly and we were well known. And yet, the people of Karaj were so fond of Farhang for his character and accomplishments, that we did not feel threatened. Even though seven innocent Baha’is of Yazd were executed, nine members of the assembly and two counsellors were abducted; even though a large number were also in prison, we were still hoping to be able to continue to serve the Baha’i community.

What happened to the Baha’i community after the assembly members were detained? Did the community disintegrate?

No, we immediately notified everyone and nine new members were elected and the second assembly formed. They were also detained and a third assembly was elected, at which time I had already left Iran. I left at the end of Azar (November-December), and learned that the members of the third assembly were also detained. The members of the third assembly were executed two at a time. Then Mr. Khomeini announced that the Baha’i administration in Iran must disband. The members of the third assembly were executed in the month of Dey (December).

At the end of my book, I have included the last letter from the National Assembly. As you can see, despite all the atrocities suffered by the Iranian Baha’i community, the tone of the letter is very respectful, the same as all the letters and complaints written to the authorities throughout these years. I myself, during the time of Beheshti, took several letters to Beheshti and Ghodoosi. But not only was nothing done in response, when the chief of staff in Beheshti’s office asked me what my business was and I told him I was a Baha’i and my husband was in prison, he said, very aggressively, “Is he still alive? You should thank God.” And he would not allow me a meeting (with Beheshti).

When was your husband, Mr. Farhang Mavaddat, detained?

Two of the prominent people in Karaj had been detained and they came to take Farhang as a witness. We found out later that this was just an excuse. Apparently those two dear souls had tried to alert us that we were being sought, but we did not receive the message. Anytime Farhang was told to go into hiding, or take our Baha’i books out of the house, he would say “I have done nothing wrong nor committed any crime, why should I hide? Also, I am a Baha’i and naturally there are Baha’i books in our home. Most importantly, I am responsible for this community and cannot leave. I have to help others as much as I can, and give them moral support. So, I cannot possibly go somewhere and hide. People need me and I cannot abandon them and flee.”

That was on 25 Mehr 1359 (17 October 1980). Actually, he went in to the court of his own accord, and from there he was never released and was kept in prison.

Who was Sheikh Mostafa Rahnama?

He was a clergyman. He had a very dirty and unkempt appearance; he was approximately 60 years old. Later on, I learned he was the head of the society for the protection of Palestinians, which trained terrorists. He had a strange animosity with the Baha’is, and apparently before the Revolution had inflicted a lot of harassment and harm on Baha’i villagers in the outlying villages. I did not know him at all until the first time he climbed the walls into our house. At one point Farhang had been detained and released. Farhang and I were eating dinner in the kitchen in the candlelight, since it was at the time of the Iran-Iraq war, during the blackouts. We suddenly heard a knocking on the door to the hallway. When we opened the door, Sheikh Mostafa Rahnama angrily said “why don’t you answer when we ring the bell?” I said “we don’t have power.” I think he clearly knew this and just wanted to torment us. He had a brother who was a colonel and a decent person. When Sheikh Mostafa was bothering the Baha’is, and making life difficult for them, we asked one of his relatives, Mrs. Tooba Za’erpoor, who was a teacher in Shiraz and a Baha’i, to come to Karaj and meet with Sheikh Mostafa and ask him to stop harassing us. When this woman went to his house, which happened to be a confiscated house, formerly owned by a Baha’i, he insulted her and threatened to kill her. Eventually Mrs. Za’erpoor was executed. The story goes that Sheikh Mostafa wife had told this Mrs. Za’erpoor that she hoped they kill him, that he was crazy.

Mrs. Mavaddat, who was Husayn Khodadoost, and why did Sheikh Mostafa raid his house?

You may have heard that the first bank was established by the Baha’is in the time of Abdu’l-Baha. Baha’is were advised to get their children accustomed to saving. Every Friday, as they attended children’s classes, they were instructed to buy a share for one Shahi, five Shahis, one or two Gharans. These shares were held at the bank. And each child was a shareholder. This was called the Nonahalan Company, and the children were encouraged to save their allowances. It was a beautiful and effective system. It also won an award in the time of the Shah. It was a bank operating with honesty and integrity. We Baha’is would invest our savings in this Nonahalan bank and buy shares, like in a cooperative, and if someone needed assistance he could get help, or could get a loan to buy a house. Mr. Khodadoost was on the board of directors of the Nonahalan Company. He also worked in a bank; that is, he was an expert in the banking business. Right after the Revolution, the Nonahalan Company was confiscated and anyone who had bought a house using a loan from the company had their home confiscated and loan recalled.

Mr. Khodadoost had a heart attack during this time, and was recovering at his house in Karaj. He was an honest, decent and respectable man, who was loved by us all. One night, in the usual manner of Sheikh Mostafa, the home of this elderly gentleman was raided. At the time his wife was away in Shiraz visiting her daughter who was giving birth, so he was by himself. The whole place was ransacked; he was told they were searching for weapons, the very same thing they told Farhang at our house.

Mrs. Mavaddat, what reasons were you given when being detained, when your home was raided? Tell us about your own detention.

I was given no reason. Even now they deny that they detained us for being Baha’is. Sometimes they suggest (Baha’is) are spies. So I ask, why don’t they produce any proof? In one of the nightly raids that led to Farhang’s detention, they came back to our house the following day and wanted to search the house again. They would not listen to our protests that they had thoroughly searched the place the previous night and there was nothing else. It was a new group, probably hoping to get a share of the loot while inflicting more pain and suffering. They would repeat the destruction and trampling all over again. After they loaded a few boxes of books in the car, they came back and said to me: “You are also a member of the assembly, and you should come with us.” They took us both with them, handcuffed us like criminals, and took me to the Azimieh prison. The agents avoided touching my hands, saying “You are unclean”, and they escorted me as they were holding one end of a stick and I held the other end.

For two weeks, I was repeatedly interrogated in the dirty and foul-smelling pens of the Azimieh detention center and the Revolutionary court jail in Karaj. The first night in the Azimieh prison I saw that Farhang was also held in one of the smelly pens. I was so happy to see he was alive and well. All through the interrogations, they would hurl insults and slander, and as soon as I said “God forgive us”, the interrogator would tell me to be quiet, that I was not allowed to mention God. Sometimes I would ask the guards nearby if I looked like a criminal or a prostitute. They told me that all Baha’i women were prostitutes.

My interrogator, throughout the interrogations, pressured me to recant my religion to be released. I would never recant my faith. Finally, after two weeks, I was released temporarily. After my release, I learned that when my father had heard the news of my detention, he had gone to my office and asked for their help to obtain my release. And, they had vouched for me, so I was released.

What was the committee for oversight on complaints and torture? Who was in charge of it? Were they responsive?

When the people were fed up and kept complaining about being tortured in prison, finally Mr. Khomeini ordered a commission be formed to look into complaints about torture. Mr. Mohammad Montazeri, the son of Ayatollah Montazeri – who was known as Mohammad Ringo – was in charge of this. He and few legal professionals were assigned to investigate complaints regarding torture. When I met this committee, I could not get over the long line of people from every walk of life, not just Baha’is, waiting to file reports.

When my turn came, I shared my story, told them how my husband had been detained and was in prison. As soon as I mentioned Baha’i, the man told me I should be thankful to God he is still alive and we have not killed him yet. I knew they would not be responsive, but wanted to have tried all options.

This committee was located in the Justice department, which was where I worked. When Farhang was detained I went to see all the judges and attorneys I had worked with to ask for their help. Although I was well liked and had good relationships with my employees, they all said that because we were Baha’is, there was nothing they could do. Everyone advised that I recant my faith. I remember asking them how they could respect someone who lies. Unlike in Islam, in which one is permitted to recant one’s faith, in our faith it is forbidden and we cannot lie. There is a writing of Baha’u’llah that says something to the effect of, ‘it is better to tell the truth and blaspheme, than to proclaim faith and then lie’.

How long did it take from the first raid on your house until Mr. Mavaddat was executed? How did you learn of his execution?

It took about nine months. When Farhang was imprisoned, it took two months for me to be permitted to visit him. In the month of April, coinciding with the Festival of Ridvan, I went to see him. They had taken him out of bed in the middle of the night and tried him. Incidentally, the details of this trial were later published in the Etela’at newspaper, which is included in my book. The last time I visited him, he said they would let us visit in person the next time. And since it was his birthday, the children had sent him a card, which he never received, since there was no next time, except for a visit with his body. I still wonder if he was being sarcastic about the visit “in person”, and if he knew there would be no more visits.

The night that Banisadr had escaped, I was sleeping at my father’s house. It was a stormy and tumultuous night. I was very sick and had nightmares all night. I don’t know, perhaps it was our emotional bond that was alerting me of Farhang’s condition. The next morning, I went to work, sick and tired. My coworkers told me they had heard on the radio that Farhang had been executed. I told them I was relieved, as I worried constantly that Farhang might recant his faith. I worried how he took all that pain and suffering and torture. That night, 100 people were killed, three of which were Baha’is – Farhang Mavaddat, Hashem Farnoush – a member of the assembly and a noble and erudite human being – and Bozorg Alavian one of the distinguished engineers. Of course, the next day four other Baha’is were executed as well.

One of Farhang’s friends, a medical examiner, had once told him: “I am ashamed of myself and my job. Many of the Mojahedin girl prisoners they bring here are raped before execution, because the guards believe they cannot go to heaven otherwise!”

When we received the body of Farhang and Mr. Farnoush from the medical examiner, they were still bleeding. This was the same day that Mostafa Chamran had been killed in the front and the city was in a state of turmoil. Even the assembly had advised the Baha’is to minimize their presence in the city, but many friends could not miss attending beloved ones’ funerals. At that time, we still had our Golestan (cemetery) and it was not yet destroyed. When their bodies were washed, we went to take pictures, and their names were written on their chests, and their charges on their legs! On Farhang’s leg, they had written anti-religion.

Did you eventually get your property back? How did you leave Iran?

Not only did they not return our car, money, gold and books, but after Farhang’s execution, our house was confiscated by the Foundation for the Destitute. After Farhang’s execution, I was officially homeless. I thanked God that we had sent our children abroad before all these troubles. Exactly two months before they started raiding our houses and looting our property, we had sent my daughter abroad. Can you imagine what would have happened to a young girl on her own, if she had been in Iran at the time?

I had to go from house to house with a bag in my hand, and I was very worried that staying with others would cause problems for the hosts. Finally, I decided to leave Iran, but that proved complicated since my passport had been confiscated in the nightly raids on the house. Finally, with the help of a friend in the city police, I was miraculously able to get a passport in two weeks, and after a very perilous and strange trip through Baluchistan, I traveled to Pakistan, then to Europe and eventually I settled in Canada.

What made you decide to write the book Flame of Tests?

I always used to keep notes of events and happenings. Of course, many of these notes were lost, but I was still able to take some of them with me when I left Iran. One of the duties of me and Farhang as members of the assembly was to oversee the needs of the persecuted and needy Baha’is. As a result, we witnessed their problems and issues. After leaving Iran, one of the duties assigned to me was to retell to others the events and hardships befallen on the Baha’is after the Revolution, to keep them apprised of their plight. For this purpose, time and time again, I have given speeches in various gatherings, in the parliaments of different countries, and throughout these years I have had interviews with English language publications, and they have always been so moved and surprised by hearing these accounts, that they have encouraged me to put these memories and observations into a book. But I have been reluctant, lest it would cause problems for the members of my family or friends still in Iran. I was serving the Universal House of Justice in the Baha’i World Center for 18-19 years, working on collecting documentation on 330 martyrs, which resulted in 12 volumes, and when I returned 8-9 years ago, I realized nothing is still confidential, that everything is available online through various websites on the Internet, and my concerns about writing a book are baseless. So, I wrote this book. Since I wanted my grandchildren to read this book, and they don’t know Persian because my sons-in-law and daughter-in-law are not Iranian, I wrote it in English – which was a difficult process. After the book was published in English, I decided to publish the original in Persian which I had written 35 years ago.

To order the book, you can access the link below:

_______

Nasrin Almasi holds a BA in Persian literature from the University of Jondishapoor, has contributed to Sayehban, a literary monthly, since 1988 when she arrived in Toronto, and since 1992 has been the Secretary of the Editorial Board of the Shahrvand newspaper.

March 3, 2018 7:33 am

Thanks.

Please also make it easier to

post these emails to G+

and to: . . . .BLOGSPOT.COM.

Thozi Nomvete.

[email protected]

March 4, 2018 7:22 am

thank you that was an incredible introduction to the atrocities inflicted upon peace loving Baha’is in Iran in a systematic way by a group of people that they should be ashamed of their own barbaric action.