Source: iranwire.com

Iran’s new education minister has used the launch of a new country-wide project as an opportunity to strike out against Iran’s religious minorities, potentially giving schools greater freedom to discriminate against non-Shia Muslim students.

“If students say that they follow a faith other than the country’s official religions and this is seen as proselytizing, they cannot continue attending school,” Mohsen Haji-Mirzaei said on Wednesday, September 11. He was referring to Project Mehr, which, according to him, his ministry had launched a few months earlier. All of the ministry’s provincial and local offices are taking part in the initiative, he said, adding that the human resources necessary for implementing the project had already been organized.

Unsurprisingly, the statements prompted unease and commotion among religious minorities in Iran, although most Baha’i citizens are familiar with such measures that deny them their human rights. Many of them have not forgotten that, while they were as school, if they said anything about their faith, they were unceremoniously expelled. Ironically, the project’s name, Mehr, not only marks the calendar month when children go back to school, but the word also means “affection,” “kindness” or “love.”

Shahin Sadeghzadeh Milani, a lawyer and the Legal Director for the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, told IranWire, “There are precedents for this and, at least for the Baha’i community, it is not something new. I have personally experienced this. I was allowed to study at middle school for three years after managers of the school who, as it happens, were not against Baha’is in schools, made me promise that I would not talk about my faith in school. Nobody there knew that I was a Baha’i, or anything about my life, the fact that my father had been executed or the unwritten agreement between me and the school officials.”

Milani believes, however, that today schools and education ministry officials have a freer hand to expel students from schools. “These statements by the minister give school officials more freedom to act,” Milani said. “Earlier, even though once in while there were reports that a Baha’i student had been expelled from school, it was not as systematically done as in universities. If they were expelled from one school they had the chance of being accepted by another school, but now this ban can be enforced systematically.”

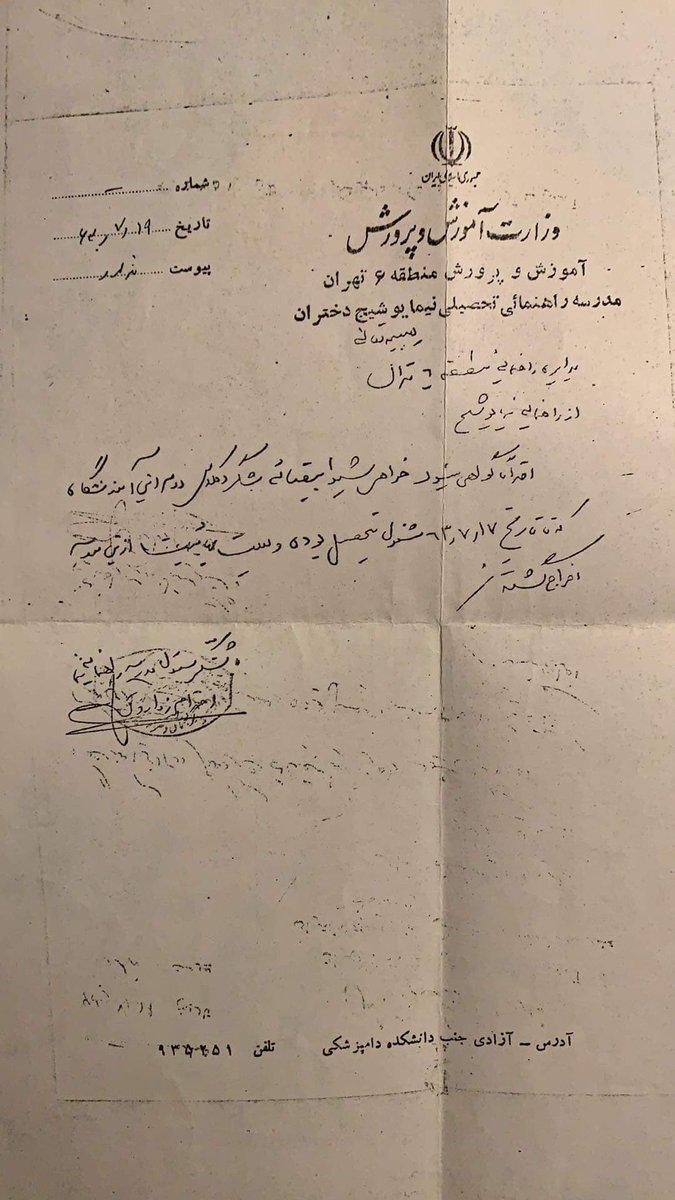

Following Haji-Mirzaei’s statements, Shadi Beyzaei, an Iranian Baha’i writer, poet and journalist who now lives in Australia, published a facsimile of a letter that expelled her sister from school in the 1980s. “My sister was expelled three times for being a Baha’i or for being born to a Baha’i family: once from primary school, once from middle school and the third time from high school,” she wrote. “This is the letter of expulsion from middle school.”

“Since this morning when I heard this news I have been in unbelievable agony,” Shadi Beyzaei told IranWire. “All the events of those years reappeared before my eyes. I know that many of my friends have had similar experiences aplenty.”

“Patriotic” in War, Outcast in Peace

Why is it that the Iranian government describes Baha’i citizens who go to war for their country as “patriotic soldiers,” but when it comes to them going to school they are a constitutionally an “invalid” minority? “The fact is that the Islamic Republic does not want to give Baha’is any concessions,” Sadeghzadeh Milani said. “It is a concession if it tells the Baha’is that they cannot serve in the military because of their faith. What they say is that if a Baha’i goes to war and he is killed, he will not enjoy the same rights as a Muslim who is killed in the war.”

Speaking further about rights, he said: “Proselytizing and expressing your opinion is part and parcel of freedom of expression and of religion,” Milani said. “The Iranian government classifies its citizens into two groups: Muslims and non-Muslims. It further classifies non-Muslims into two groups: religious minorities as defined by the law and those who are not recognized by the law. But none of these [legal provisions] deprive an individual of the right to free speech.”

Hamed Farmand, the president of the US-based group Children of Imprisoned Parents International (COIPI) echoed Milani’s argument. “What Mr. Minister Mohsen Haji-Mirzaei is saying is very simple,” he tweeted, “‘We ask you about your religion. If you tell the truth that you are a Baha’i then we expel you.’ His excuse this time is ‘proselytizing’ but at its core it is nothing other than religious discrimination and the violation of religious freedom, even though Iranian law does not prohibit religious proselytizing.”

Some Iranian human rights activists argue that the introduction of a so-called “punishing the deviant sects” bill to the parliament has prompted a more public airing of the government’s policy of expelling Baha’i students. In effect, if this bill is passed, “inquisition” would gain the force of law and people can be punished as criminals for merely holding an opinion or following an unapproved religious faith. Rights activists argue that it would be a dangerously unjust law, especially considering that, even before the law has been passed, the Iranian judiciary uses trumped-up and baseless charges to punish dissent and religious minorities.

“I have no idea how much the education minister’s statements are related to this bill and its chances for passage in the parliament,” Milani said, “but as far as I know the bill was introduced at the parliament after some judges acquitted Baha’is who were charged with activities against national security by proselytizing Baha’i religion. Earlier, this charge was enough to condemn the defendants, but now it appears that the Iranian regime and the legislators are looking for a way to create a separate charge with ‘proselytizing Baha’i religion’ [having] its own punishment that, it is said, would be around five years in prison.”

In January 2019, Lisa Tibanian, an Iranian Baha’i woman accused of “propaganda against the regime,” was acquitted in a verdict that stated belonging to the Baha’i faith or proselytizing were not crimes. The verdict was issued by Judge Ali Badri, the presiding judge of Branch 12 of Alborz province’s Revolutionary Court of Appeals. The judge stressed the fact that the defendant accepted the sovereignty of the Islamic Republic and this was an important reason for not finding her guilty.

According to the judge, proselytizing is a crime under Article 500 of the Islamic Penal Code only if it is aimed against Iran’s political system. Otherwise, the judge said, “religious proselytizing in a way that cannot be construed as being against the Islamic Republic of Iran and its regime is not a crime.” He also stated that punishing someone for proselytizing on those terms “would even violate citizens’ rights under the constitution.”

Beyond the Baha’is

But Baha’is are not the only Iranian citizens who reacted to the education minister’s statements. The Islamic Republic constitution fails to recognize many other religious minorities as “legitimate” religions, particularly religions practiced by people in western Iran. These include Yarsanism, also known as Ahl-e Haqq (“People of Truth”), the Yarsan, Kaka’i, and Ali-o-Allahi (“Worshipers of Ali”), a syncretic religion founded in the late 14th century. Their numbers in Iran is estimated to be between two and three million, most of whom live in Kurdish areas of Iran.

Reza Shahmoradi, a Yarsan who lives in Australia, says the ruling the education minister announced “does not only affect Baha’is but also the Yarsan. We are even ignored by the so-called reformists. Unfortunately, we don’t have a media outlet that could provide us with accurate statistics of violations of human rights in extremely deprived areas where the Iranian Yarsan community lives. But I myself was rejected when I wanted to enroll in the Teachers’ College when I said I was a Yarsani.”

Shahmoradi says that the Yarsani minority has always been forced to hide its identity to enjoy the most basic human rights. “Put in simple terms, this statement by Mr. Minister means that a Yarsani has no right to education unless he pretends to be a Shia Muslim,” he said. “This is not something new. For years now, we have hidden our identity. To express our identity is the same as proselytizing and the result would be the denial of our most basic rights. This was revealed even as far back as November 10, 1988, during the premiership of Mr. Mir Hossein Mousavi in the circular number 618. This circular acknowledged that Yarsans were denied government employment and even education in the areas where they lived.”

Even though the Yarsans are [one of] the biggest religious minorities in Iran,” he says, “they have always been ignored. We hide are identity because we had no support. We knew that nobody heard our voice outside Iran or inside the borders of this bejeweled realm.”

Shahmoradi also has criticism for the media that reported the recent news. “Most domestic and foreign media wrote that the education minister has said that a student would be expelled if he proselytizes a religion not officially recognized,” he says, “whereas he clearly said that if a student says that he belongs to a religion not officially recognized he would not be allowed to study. These two things are different.”

Surprised by Candor

“As you know, this has been the practice in all these years,” a teacher and union activist who asked to remain anonymous told IranWire. “But unfortunately, the media was surprised because the responsible authorities had never talked about it so openly. When Baha’is were denied [the right to] enroll in universities, it was presented as [a case of them submitting] ‘incomplete dossiers.’ The circulars were confidential and were issued behind closed doors, but now Mr. Minister publicly cites proselytizing as reason for expulsion from school. But the important point here is that even the four religious minorities recognized by the constitution can be in trouble if the question of proselytizing is raised, even though they are not treated as badly as the Baha’is are.”

The teachers’ rights activist IranWire spoke with expressed sorrow that the education minister is encouraging religious minority students to lie. “The Shia’s call this taqiyya [dissimulation], meaning that if they are in a precarious situation or if their lives are in danger they can hide the truth and lie,” he said. “But the teachings of another religion might prohibit lying, regardless of why. This is really weird. He is explicitly saying that you will be expelled if you tell the truth. That is why religious minorities in Iran say goodbye to their birthplace after finishing school and college because they know they have no place in the higher echelons of management, regardless of how talented or efficient they might be.”

In response to the widespread criticisms, the education minister used its Twitter account to deny it had stated anything controversial: “Free and quality education is the right of all children. Nobody should be denied an education for holding a belief. Nobody in schools has the right to be an inquisitor [but] Illegal sects must not be allowed to proselytize in schools. Schools are for rightful and lawful education.”

It would appear that the new government appointee to the important job of education minister has a somewhat different interpretation of what “inquisition” means.

Leave a Reply