Source: iranwire.com

Kian Sabeti

Health workers are the front line in our defense against the coronavirus pandemic – including hundreds of Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. But they are not in Iran; instead, they live in countries around the world, treating their patients, where they are admired and praised by the people and governments of the countries where they live. The one country where they cannot do their work is Iran.

Many of these doctors and nurses – who studied and served in Iran – lost their jobs after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. They were expelled from the universities and their public sector jobs, barred from practicing medicine, jailed and tortured, and a considerable number of them perished on the gallows or in front of firing squads.

The crime of these Baha’i doctors, nurses and other health workers was their faith in a religion that the rulers of the Islamic Republic believe is a “deviant” faith.

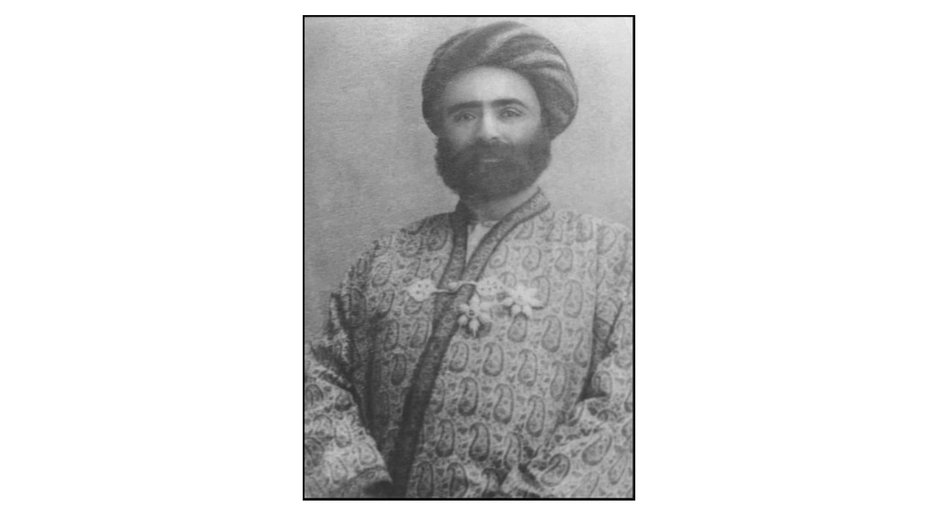

In a new series of articles, called “For the Love of Their Country,” IranWire tells the stories of some of these Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. In this installment you will read the story of a forebear of these modern doctors, Siyyid Muhammad Ala’i Nazimu’l-Hukama, a 19th century physician who became a prominent doctor and humanitarian despite the persecution he experienced as a Baha’i.

If you know a Baha’i health worker and have a first-hand story of his or her life, let IranWire know.

–

My great-grandfather Siyyid Muhammad Ala’i would never have become the Nazimu’l-Hukama – chief physician to the court of Iran’s king, the Shah – had he not first been accused of heresy by his family and peers and forced to leave his home. The story goes that, years later, around 1882 when he was 29 years old, Siyyid Muhammad graduated from Tehran’s medical school as its most outstanding student. Iran’s ruler Nasir al-Din Shah attended the ceremony, and was so impressed with Siyyid Muhammad that he appointed him to the royal court as the Anthony Fauci of his day.

Holding the title and post of Nazimu’l-Hukama meant that my great-grandfather was a member of the elite and famous as a doctor. He was so trusted that, during a plague outbreak, the Shah asked him to remove the Crown Prince from Tehran and to look after his health.

Iran saw repeated pandemics in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The outbreaks of plague, cholera and typhoid may have killed up to a million people – from a population of eight million – during the 19th century. Millions more starved in famines triggered by the agricultural decline which followed such widespread death. Public health systems or state subsidies for the poor were either rudimentary or hadn’t yet been invented.

Today’s coronavirus pandemic has claimed 51,000 lives in Iran, according to official figures, though the true number is thought to be more than twice as high. Untold economic dislocation has afflicted people who were already suffering from rising prices and collapsing wages. Iran is so short of health workers that some doctors and nurses with Covid-19 are being forced to work – some of whom have waited months for their salaries. Officials warn the death toll may rise to four-digits a day and in November an Iranian died from Covid-19 every three minutes. Patients have been forced to line up outside overcrowded hospitals.

Iran’s current health and economic crisis is harrowing. And though it has not claimed an eighth of the population, as was the case in the 19th century, Iranians today are suffering in ways that were experienced by their ancestors just a few generations ago.

Nazimu’l-Hukama was on the front line of 19th-century responses to disease and poverty. He held a private clinic each morning before tending to the Shah’s garrison in the afternoons. And though he must have been well-paid for this work, he was often obliged to tell his children – of whom he had 12 – that he had no money for them because he had refused to charge his less fortunate patients. He sometimes even paid for their medicines.

A biographical sketch of Nazimu’l-Hukama by one of his grandchildren records that during one famine, perhaps around 1917 to 1919, when as many as two million people died, he was known to stand outside a Tehran bakery day after day to give bread to the poor. Tehran residents had widespread confidence in his skills. People said his hands held a certain comforting warmth – and he was credited with saving thousands from typhoid. In his memoir Nazimu’l-Hukama also writes that, during one influenza outbreak, his home was filled with patients. The flu sufferers stood, sat or lay wherever they could, filling the rooms and corridors, all of them seeking his care.

Mothers with children on their deathbeds would visit Nazimu’l-Hukama to appeal for help. He knew there was nothing to be done for these cases. But still he visited the children’s bedsides to comfort them and their mothers if they were beyond saving.

Nazimu’l-Hukama believed that any power of his to heal – and perhaps also his power to comfort patients, to help them to suffer less – came not from himself but from his faith in the grace of God.

My great-grandfather’s healing touch was not always fated to work. His first daughter, Rubabih, died from an illness after a visit to Haifa in Palestine. Rubabih was only in her 30s or 40s – the exact year isn’t recorded – and although Nazimu’l-Hukama mourned her loss he also comforted the rest of his family. “Do not complain and grieve,” he said. “Rubabih is released from the hardships and difficulties of the world.” And his eldest son Ziya, who was also a doctor and who worked for a time in Nazimu’l-Hukama’s clinic, died while treating patients during a typhoid outbreak.

Nazimu’l-Hukama had long since trained himself to overcome hardship. His difficulties – the years of isolation and poverty that he suffered in Tehran, when he was still simply Siyyid Muhammad, after the separation from his family – were only resolved through education. A benefactor’s generosity, combined with his own small income from tutoring, made it possible for Siyyid Muhammad to study medicine. “First education, then lunch and dinner,” he would later tell his children, a watchword born of his own experience.

Education was so important to my great-grandfather that, during his successful years as Nazimu’l-Hukama, he helped establish the Tarbiyat School in Tehran. Tarbiyat means “good upbringing” or “training” and the school was one of Iran’s first secular educational institutions. Children from Iran’s ruling elite and the new middle class attended the school. Education in Iran before the late 19th century was limited to traditional subjects such as literature and calligraphy; or, for the clerical class, Islamic studies, Arabic, jurisprudence and metaphysics. And most Iranians at the time were only trained for agriculture or trade. The Tarbiyat School helped to break this traditional and religious grip while also opening education to larger groups of people.

My great-grandfather’s passion for education extended also to the women in his family. He insisted that his daughters receive an education and, when he married his third wife, who was many years younger than him, he also encouraged her to continue studying after their marriage.

Siyyid Muhammad’s first education was not medicine – and his first home was not Tehran. He was born in 1853 and grew up in the northern city of Lahijan near the Caspian Sea. One of his uncles sponsored him to be trained as a cleric. Graduating ahead of his peers at the age of 17, Siyyid Muhammad came to be called the “interpreter” of Quranic traditions and many people asked him to write his interpretations of scripture in the margins of their books. He was married, had a young child and – by all outward measures – was ready for a life of local grandeur.

But Siyyid Muhammad was also a rebel. A friend introduced him to radical new teachings that were to remake his life, transform his beliefs and turn him into the doctor to the rich and famous as well as the poor.

Iran in the 1870s, when Siyyid Muhammad was training to be a cleric, was dominated by its Shia Islamic traditions and leaders. Women were second-class citizens. Zoroastrians, Jews and Christians were termed “People of the Book” and enjoyed some protections under the law. But other religious minorities were attacked as “unclean” apostates by many clerics who said they were a threat to Iran’s traditional beliefs. The clerics were afraid that any new teachings might loosen their hold on the masses – so they sometimes incited mobs and the Shah to commit violent acts against these minorities.

Thirty years earlier, from 1844 to the 1850s, this had happened to 20,000 members of a new religious movement. The members of this movement – which evolved into the Baha’i faith – were massacred for their beliefs. The Baha’i faith taught the oneness of humanity and religion, the equality of men and women, the right to universal education and the elimination of all forms of prejudice. A hundred years later, when the clerics became the government after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the persecution of the Baha’is once again became a policy that persists to this day.

Siyyid Muhammad was forced to leave his home because he too had chosen to follow the Baha’i teachings. I’m told that the walk from Lahijan to Tehran is now a popular three-day hike. But for my great-grandfather, then aged 19 and leaving behind his wife, daughter, his family and everything he knew, it was a trek into years of isolation and pain. He had no provisions but a small bag of rice which had to sustain him across days and miles of terrain.

The first decade in Tehran was spent in poverty. One of Siyyid Muhammad’s uncles had told him: “I can see you dying of starvation and misery in the corner of a forsaken room, with not a friend beside you.” The prophecy almost came true – but for Siyyid Muhammad’s own faith in his choices and beliefs. Slowly and over a decade, he worked his way up; first by tutoring seminarians, then through medical school, before graduating with laurels and rising to the top of his field. Years later he was to reconcile with his family.

Nasir al-Din Shah and others at court must have known that Siyyid Muhammad Ala’i Nazimu’l-Hukama, who was always outspoken in his beliefs, was a Baha’i. His rank was perhaps his shield. Other Baha’is were in prison and he would visit them during his medical rounds for the inmates.

Siyyid Muhammad’s 12 children, 52 grandchildren and uncounted great-grandchildren have now spread to most corners of the world. The youngest child, his daughter Shokat, passed away in 2020 at the age of 99 in the faraway land of California. I met her: she was so shrunken from age that we were eye-level when I sat and she stood. A century of life shone from her face. Shokat lived 32 years longer than her father – who had passed away at 67, in 1920 – and her life took her from Tehran to Sri Lanka before she settled in Orange County. But I know she would tell us that her own road wasn’t half as long as the road that Siyyid Muhammad walked from Lahijan.

Leave a Reply