Source: www.bbc.com

By Mehrzad Fatuhi, Shahab Mirzaei

Translation by Iran Press Watch

The 1979 victory of the Islamic Revolution in Iran gave the ruling clerics a great opportunity to vent their long-standing animosity against the “Babis and Baha’is” of Iran.

The destruction of the historical house of Ali Mohammad Bab in Shiraz in September 1979 was one the first acts in an ongoing campaign of persecution against the Babis and Baha’is that continues today. Not only the living, but even the dead of the Babis and Baha’is have not been spared,

The persecution of Babis, Azalis and Baha’is began during the Qajar era in Iran in the mid 1800’s. Ruling clerics and authorities, fearful of the influence of the Bab, stirred up public animosity through disinformation. In towns and villages Babis were apprehended, paraded through streets, burned with candles, stabbed, and stoned. Many were murdered in the streets; others imprisoned and executed. Tahirih Qurrat al-‘Ayn, a Babi leader and champion of women’s rights, was the first woman to remove her headscarf and was vehemently condemned by the Shia clerics. She was imprisoned, placed under house arrest, repeatedly questioned and harassed. In 1852 she was taken to the Ilkhani Garden, strangled, tossed into a well and stones were hurled upon her lifeless body. In 1850 the Bab Himself was executed, after a series of imprisonments and exiles, executed in Tabriz, Iran, by a volley of 750 rifles. His body was discarded in a moat. Baha’u’llah was exiled with his family to Baghdad and later Palestine. He remained a prisoner of the Persian Government and the Ottoman Empire until his death in 1892. The persecutions against Babis, Azalis and Baha’is continued throughout the Qajar Dynasty and into the Pahlavi era.

During the Pahlavi era, Baha’is were harassed in various ways by the government and society. Mehrdad Amanat, a history researcher, wrote, “Mohammad Reza Shah, who in the early years of his rule sought to strengthen the weak pillars of his monarchy, did not hesitate to associate with traditional Shiite scholars. For example, in 1916, the Shah responded agreed with Ayatollah Borujerdi’s request to attack the Baha’is as a reward for the clergy’s cooperation in suppressing the National Front and the Tudeh party. Public disinformation spread about Baha’is inflamed the populace against them. Baha’is suffered public attacks in many villages and cities. Many were murdered and their bodies defiled.

After the coup d’état on August 28, 1953, the Haziratu’l-Quds (Baha’i Center, the current location of the Islamic Propaganda Organization) was occupied by the Imperial Army, with Major General Mohammad Batemanqlich and Mohammad Taghi Falasfi together launching the first strike in destroying the Haziratu’l-Quds building.

According to Mr. Amanat, this anti-Bahá’í attitude was among the major grievances of the opponents the Pahlavi government’., “During the short period of the 5 June 1963 rebellion, some citizens attacked the Baha’i cemetery in Tehran, damaged graves, and burned the bones of the deceased.” Contemporary historian Hamid Tavakoli Targhee says that it was during these years that “the anti-Bahá’í movement became an integral part of the Islamist movement”.

Mohammad Mossadegh (Prime Minister of Iran, 1951 – 1953) was a notable, and perhaps the only, exception to this anti-Baha’i sentiment. Mohammad Taghi (Iranian philosopher, musician and researcher ) wrote in his memoirs about a conversation where Ayatollah Falsafi related, “On the orders of Grand Ayatollah Boroujerdi, I went to see Dr. Mossadegh and conveyed the message of the Ayatollah that since the Baha’is are active in the cities, he felt it necessary for you to take action in this regard.” In response, Dr. Mossadegh laughed loudly and said, “Mr. Falsafi, in my opinion, Muslims and Baha’is are not different, they are all from the same nation and Iranians.”

According to Mina Yazdani, professor of history at Eastern Kentucky University, despite Dr. Mossadegh’s inclusive national vision, personal integrity, and resistance to the Ayatollah’s desire to “legalize” persecution of the Baha’is, it could not prevent the influence of religious forces in inciting the killing a number of Baha’is, or the release of the perpetrators without punishment.”

Towards the end of the Pahlavi era, the discrimination and harassment of Baha’is decreased, allowing Baha’is more freedom to practice their face and administer to their communities. However, with the establishment of the Islamic Republic, the longstanding aminos towards Baha’is fomented a systematic and comprehensive campaign of persecution of the followers of this faith. News about the arrest, execution, and disappearance of Baha’is, along with attacks on their homes, fields, and cemeteries, became common and was heard from all over Iran.

In the first attack on the National Spiritual Assembly of Baha’is of Iran, on August 1980, eleven Baha’is were abducted and “disappeared”. Abdul Hossein Taslimi, Houshang Mahmoudi, Ebrahim Rahmani, Hossein Naji, Manouchehr Qaim Maghaki, Attaullah Moqrabi, Yusuf Al-Gadi, Behieh Naderi, Kambiz Sadeghzadeh, Yusuf Abbasian and Heshmatullah Rouhani were taken during a raid. To this day the exact nature of their fate is unknown.

On December 13, 1981, Revolutionary guards arrested members of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of Iran, Ginous Mahmoudi, Kamran Samimi, Mahmoud Majzoub, Jalal Azizi, Mehdi Amin Amin, Ezzat Farohi, Sirous Roshni, and Ghodrat Rouhani. On December 27, 1981, all were executed, without trial, by firing squad. Abdul Karim Mousavi Ardabili, Chief Justice of Iran Head of Supreme Court of Iran judiciary at the time, claimed they had been executed for “espionage for foreign powers”. This was and continues to be a common, although baseless, charge levied against Baha’is.

Hassan Mousavi Tabrizi, the Prosecutor General of the Revolution, stated in an interview: “Bahá’ís spy for others and provoke and disrupt some things. “I announce today that because of these vandalisms and wrongdoings that are done in Baha’i organizations, these organizations are known as warring and conspirators from the point of view of the Revolutionary Prosecutor’s Office in the Islamic Republic of Iran, and it is forbidden to work in their favor in any way.”

As a point to how baseless such charges are, is important to note that the Baha’i Faith specifically prohibits adherents from participating in any forms of sedition, including espionage.

According to Baha’i sources, during the first 8 years of the Islamic Revolution, 243 Baha’is were killed or executed: 7 in 1978, 11 in 1979, 37 in 1980, 55 in 1981, 28 in 1982, 27 people in 1983, 28 people in 1984, 4 people in 1985 and 10 Bahais in 1986.

According to historical researcher Mehrak Kamali, “With the continuation and increase of government pressure on the Baha’is, the Baha’i National Assembly officially accused the government officials of organized anti-Bahá’í (activity), and at the same time, the Islamic rulers emphasized more and more that they are enemies and tried to exclude the Baha’is from society. “

In the 1983 letter from the Baha’i community, addressed to the government officials of Iran, it was stated: “The difference is that previously the fatwa of killing was issued explicitly in the name of religion and was implemented by the ruler. Today, when the scholars themselves are rulers of the government, they plan to throw them (Bahá’ís) into prison with political charges, so that they will be sentenced to death in the Revolutionary Court, and since the ruling is from the Ruler of Sharia, there is no objection, no need for a lawyer, trial, and formalities. There is no need for proof and evidence, and there is no use for constitution and legal standards.”

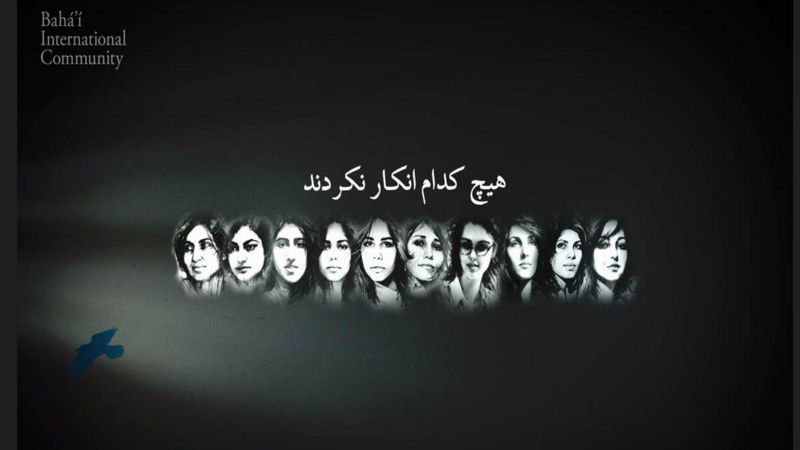

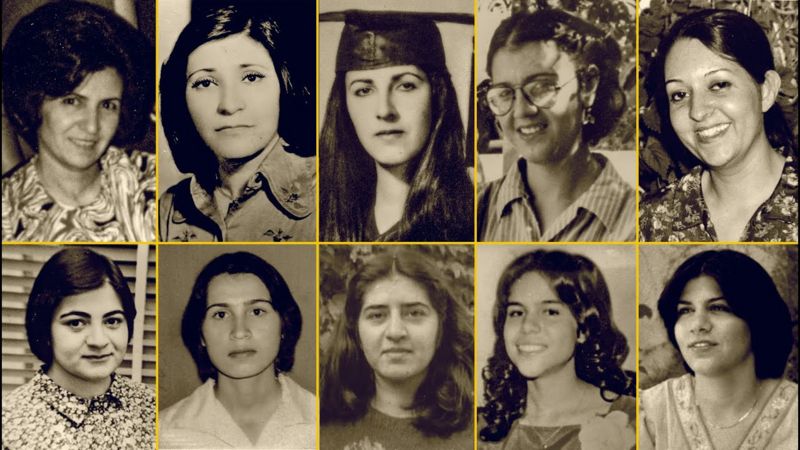

10 Gallows for Ten Bahai Women Who Kissed the Gallows When Given Choice Between “Islam and Execution”

On the morning of June 16, 1983, six Baha’i men, who had refused to recant their Faith when faced with the question of “Islam or execution”, had been executed by hanging in the polo field of Shiraz. Two days later, 10 Baha’i women, who had refused the same choice and stood firm in their faith, were also executed by hanging. They were among the 22 Baha’is whom President Ronald Reagan, of the United State, had publicly requested their release after the news of their death sentence was published.

On May 22, 1983, the New York Times quoted White House officials as saying that President Reagan called on the Iranian government to stop the execution of Baha’is in a statement. In the statement of the President of the United States, the world leaders were asked to join him and ask Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the Islamic Republic at the time, not to “implement the orders issued against these innocent people.”

Mr. Khomeini, in response to the meeting with government officials and the Revolutionary Court, read the “support” of the then American president Reagan as a proof that these people were spies and said: “Mr. Reagan says that these homeless Baha’is are peaceful people who are busy performing their religious duties, and the Iranian government has arrested them because of their religious belief, which are contrary to the beliefs of the Islamic Republic. If they were not spies, you (Americans) would not have complained. You support them because they do your job.”

The founder of the Islamic Republic added that if “we have no other reason that they are American spies, then Reagan’s support for them is enough. If we don’t have any other reason that the Tudeh Party are all spies, Russia’s support for them is enough to arrest them.”

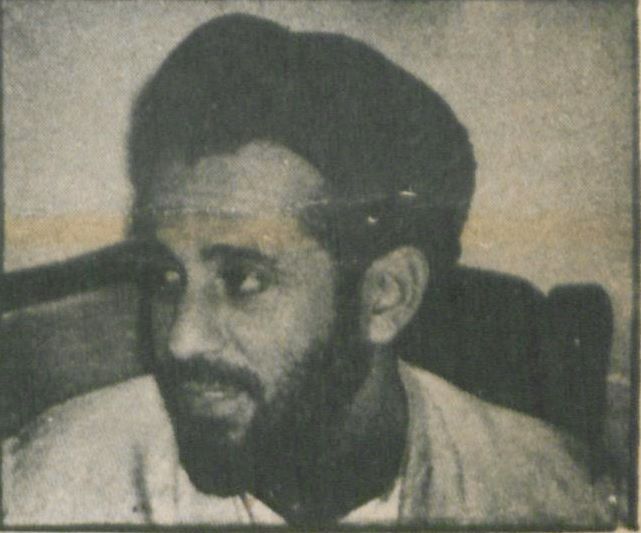

On March 15, 1983, Zia Miremadi, the general and revolutionary prosecutor of Shiraz, gathered the imprisoned Baha’is in a hall and told them that the sentence for all but a few was death. He said that these rulings have been approved by the Supreme Judicial Council and once again said that any Baha’is who convert to Islam will be freed.

According to Mr. Miremadi’s order, late in May of 1983, each of the imprisoned Baha’is was given the opportunity to renounce their beliefs in the Baha’i Faith and so-called “repent”.

The death sentence of these Baha’is, carried out in coordination with Mohiuddin Haeri Shirazi, the Imam of Friday of Shiraz, and the provincial Guards Corps, was published in a short news item in the “Khabar Jonub” newspaper. The death sentences were carried out shortly after.

In late July 1983, Zia Miremadi, the public and revolutionary prosecutor of Shiraz and the issuer of death sentences, defended the action of the Revolutionary Court in an interview with “Khabar Jonub” and once again made accusations such as “collaborating with SAVAK, spying for Israel and meeting with Reagan and American leaders” in 1983 when these people were in prison.

He went on to mention that “there is not the smallest place for Baha’i Faith and Baha’is in the Islamic Republic of Iran” and referred to them as “enemy apostates” (enemy apostates can belong to the”people of the book” or to the non-“people of the book”. There is no protection of their life, property, and security in the Islamic government.)

Mr. Miremadi was a public prosecutor in Tehran from 1983 to 1988. He was arrested in 2002 for the crime of corruption by the Clergy Court, but he was released after a while and now he is a member of the Bar Association and has a law office in Tehran.

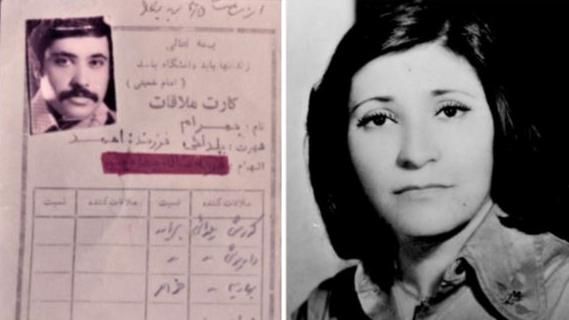

Zarrin Moghimi Abyaneh: “Now Where Should I Go to be Executed?”

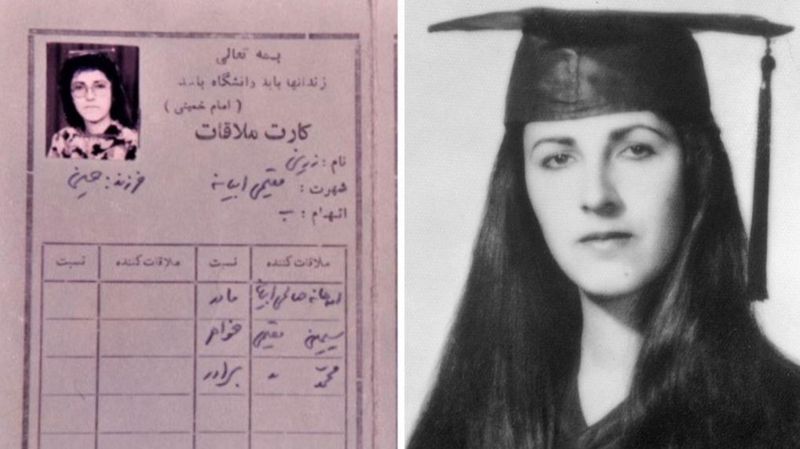

Zarrin Moghimi Abyaneh was 29 years old and was executed along with 9 other Baha’i women.

Two years before she spent the last days of her life in Adel Abad prison in Shiraz, after meeting a friend, she wrote describing this prison: “Amidst the high heavy walls, souls bigger than the walls have been imprisoned; there, from each of its stones, the cry of amazement and wonder is loud.”

Zarrin was born in Abianeh in Isfahan province and lived in Tehran with his mother and father. She received her bachelor’s degree in English from Tehran University.

Hossein Moghimi, Zarrin’s father, was a plasterer and in 1972 the family moved to Shiraz on behalf of the Iranian Baha’i community for Mr. Moghimi to work on the restoration of the house of the Bab.

On December 8, 1982, Zarrin was arrested along with her parents at their home. Her mother was released after 5 months, but her father remained s in prison for two years after Zarrin’s execution.

Zarrin’s sister, who was out of Iran at that time, repeatedly asked her sister to leave that country. Zarrin said that she would never leave Iran.

Olya Ruhizadegan, Zarrin’s cellmate (with the 9 other Baha’i women who were hanged). She talks about the bravery of Zarrin Moghimi in her book of memories that she published in English and titled “Olya’s Story”.

It is said that when Zarrin came from the last session of interrogation and pressure to renounce the Baha’i Faith, she said to the court official: “Okay, now where should I go to be executed?”

Five days after this meeting, she was hanged along with 9 other women.

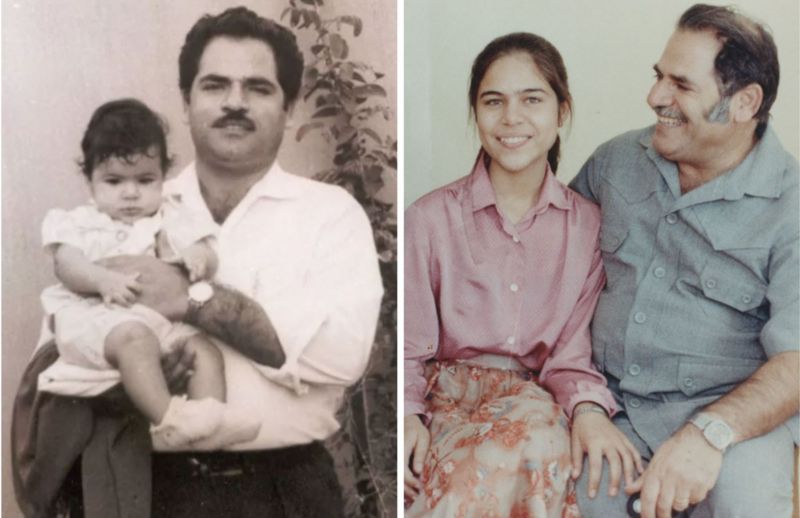

Mona Mahmoudnejad; Execution of a 17-Year-Old Girl follows the Execution of Her Father

Mona Mahmoudnejad was born in Aden, the capital of South Yemen. She was 4 years old when her parents returned to Iran from Yemen. They first settled in Tabriz and later moved to Shiraz.

Mona was a high school student when she was arrested in Shiraz along with her father Yadullah Mahmoudnejad, on the evening of October 23, 1982. Mona and her father were first taken to the IRGC detention center, but later were transferred to Adel Abad prison in Shiraz along with five other Baha’i women.

About three months after her arrest, the judicial authorities asked Mona’s mother, Farkhundeh Mahmoudnejad, for a bail of 500,000 tomans for her daughter’s release. The bail was paid, however, not only did not release Mona, but they arrested her mother and took her to Adel Abad prison.

Mona’s father was executed by hanging on March 12, 1983, along with Rahmatullah Vafai and Tuba Zairpour. Mona’s execution followed three months later.

Mona’s body was not handed over to the family and it is said that the government agents buried her in the Baha’i cemetery of Shiraz.

Nusrat Ghofrani and Bahram Yaldai; A Mother and a Son Who Were Executed Two Days Apart

Nusrat Ghofrani (Yaldai) was hanged at the age of 46, two days after the execution of her 28-year-old son, Bahram Yaldai. Her husband later said, “He never found out whether Nusrat knew about our son’s execution or not.”

Mrs. Ghofrani along with her husband Ahmed Yaldai and their son Bahram Yaldai were from well-known Baha’i families in Shiraz. Their house was a refuge for persecuted Baha’is in Shiraz.

The family members were arrested in their home at 9:00 PM on October 23, 1983. This occurred during a wave of the Baha’i arrests were being carried out.

Mrs. Ghofrani was placed in solitary confinement in the IRGC detention center for a period, but she was later transferred to Adel Abad prison in Shiraz.

It has been said that Ms. Ghofrani was the target of verbal and physical abuse by fans and members of the Hojjatiye Association, a radical Shiite group that was formed in 1953 for the purpose of fighting against the Baha’is and any influence they might have among the people in Iran. In the early years of the revolution it was openly active.

Mrs. Ghofrani, of the 10 Baha’i women executed on June 18, 1983, was the only one who was not taken to the “repentance meeting”.

There are no documents detailing her trial and Ms. Ghofrani was denied the right to have a lawyer.

Tahirih Arjamandi and Jamshid Siavoshi; A Loving Couple Who Were Hanged

Tahirih Arjamandi was hanged on June 18, 1983, at the age of 30, two days after the execution of her husband, Jamshid Siavoshi. She and her husband were known Baha’is.

Mrs. Arjamandi graduated from Tehran University, where she studied nursing. She had extensive experience working in several hospitals in Tehran, Yasouj and Shiraz.

Two years before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Mrs. Arjamandi and her husband, Jamshid Siavashi, migrated to the city of Yasouj, the capital of Kohgiluyeh province, and Boyar Ahmad to help form the “Local Spiritual Assembly”. After the revolution, their home was attacked, and they were forced to leave Yasouj and move to Shiraz.

According to the documents available in the “Archives of Baha’i Persecution in Iran”, Mrs. Arjamandi faced work restrictions due to her Faith while in Shiraz, and barely managed to get hired as a nurse in a private hospital.

At the end of October 1982, Jamshid Siavoshi was arrested in his home in Shiraz. Forty days later, agents returned for another of many raids on their home and this time took Tahirih into custody.

As with other Baha’is detainees, Tahirih Arjamandi was transferred to the IRGC prison in Shiraz following her arrest. She and her husband were subjected to intense pressure from the interrogators to recant their belief in the Baha’i Faith.

She told her family that it was enough for her, that when she is in the cell, she feels that Jamshid is also behind one of these doors and is close to her.

It has been reported that interrogators threatened her many times with torture prior to the execution of her husband, and even once “falsely” told her that her husband recanted his faith.

Once in prison Mrs. Arjamandi was allowed to see her husband. According to the “Archives of Baha’i Persecution in Iran” quoting by Mrs. Arjamandi’s cellmate, Jamshid Siavashi had been severely tortured and when Tahirih Arjamandi returned to the cell from visiting him, “she was in a state of convulsions and was shaking violently and crying.”

Tahirih Arjamandi and her husband were both eventually transferred from IRGC detention center to Adel Abad prison in Shiraz. They remained in that prison until the execution of their death sentence.

Both were denied legal counsel, and there are no accessible records of any trial proceedings.

Akhtar Sabet Sarvestani; Eviction and Execution

Akhtar Sabet Sarvestani was not even 25 years old at the time of her execution. She was born in Sarvestan city of Fars province.

Akhtar studied in Sarvestan until the 9th grade, then went to Shiraz to continue her education. After receiving her diploma, she returned to Sarvestan. After passing the exam at the Nursing Education Center of Shiraz University, she returned to Sarvestan again. Akhtar continued her studies in the field of nursing until receiving her associate degree. After the cultural revolution of 1980, she was expelled from the university along with other Baha’i students.

The same year, Akhtar was employed in the children’s department at Saadi Hospital in Shiraz and continued working there until her arrest.

IRGC agents arrested her at her home on October 23, 1982. After 38 days, she was transferred to Adel Abad prison in Shiraz.

Shahin Dalvand; I Stay in Iran

Shahin Dalvand was 26 years old when she was executed. She had been called Shirin since childhood.

She was studying sociology at Shiraz University. She was in her last year of university during the 1979 revolution.

It was at that time that her family immigrated to Britain, but Shirin chose to stay with her grandmother in Shiraz to finish her education. When her father called Shirin to come to Britain, she told him that despite all the problems and difficulties faced by the Baha’is, she had decided not to leave Iran.

Shirin titled her thesis “Research on the Characteristics of a Group of Addicts and the Causes of their Tendency to Addiction”. It was welcomed by university professors, and they invited Shirin to participate in a television program. However, because she was a Baha’i, she was not allowed to participate in that program.

On November 29, 1982, she was arrested with another group of Baha’i youth. They were taken to the IRGC detention center. A month later they were transferred to the IRGC Ward 1 in Adel Abad prison.

She was only able to visit her grandmother while in prison.

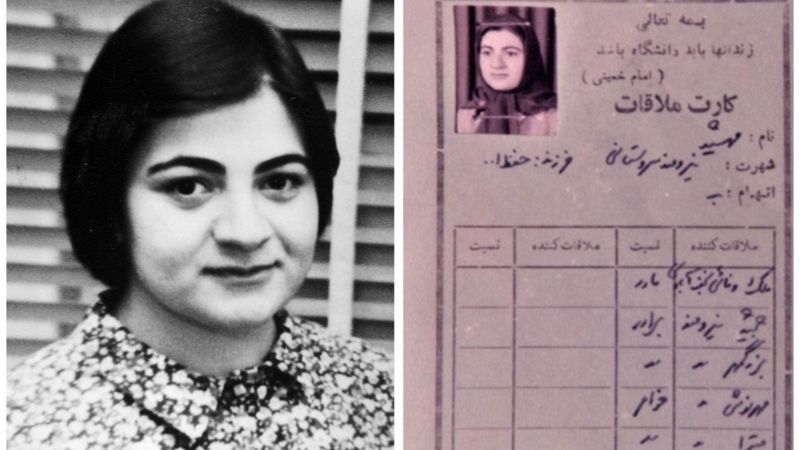

Mahshid Niroomand Sarvestani; Home Invasion at Night

Mahshid Niroomand Sarvestani was arrested at the age of 27. She was born in Shiraz and was the third child and the first daughter of Hefzallah Niroomand and Malekeh Vafaei. Niromand’s family lived a simple life. Mahshid’s father was a technical worker and radiator maker.

Mahshid studied physics at Shiraz University and earned diplomas in English, German and French. Following graduation, she started teaching physics and chemistry. Unfortunately, being a Baha’i Faith prevented her from retaining employment.

Around midnight on November 29th, 1982, government agents stormed the Niromand’s family home, arrested Mahshid and took her to the IRGC detention center. Mahshid remained there for 48 days before being transferred to Adel Abad prison.

Mahshid, who did not want to cause her mother and father to worry, did not tell them anything about her experiences during her detention. Under interrogation she was pressured to renounce her Faith and also to tell interrogators the names of other Baha’is. She refused to do either.

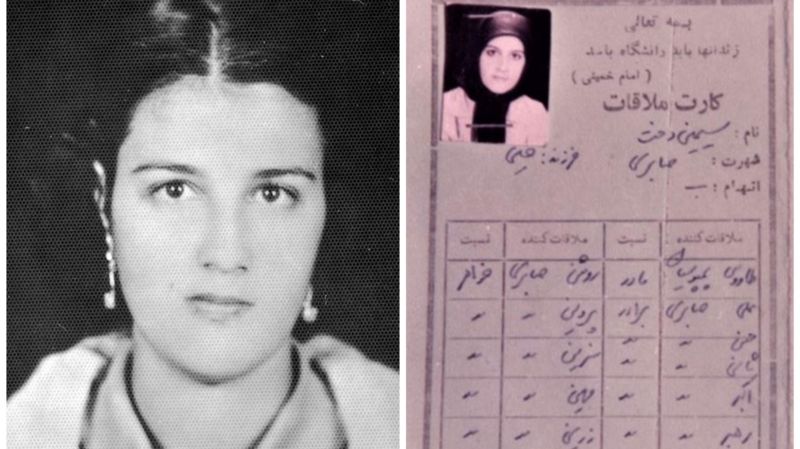

Simin Saberi: “Don’t Expect Me to Get Out of Prison”

Simin Dokht Saberi was 24 years old when she was executed. She and her family, like many Baha’i citizens, had experienced persecution from the first days following the revolution in Iran. Their home had been raided, personal and family property confiscated, and dismissal from work due to their being Baha’is.

Hossein Sabri, her father had converted from Islam to the Baha’i Faith. Their family lived in a garden near Shiraz.

One night in 1979, three nights after the victory of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the Saberi home, as well as several other Baha’i homes around Shiraz were attacked. Stone were thrown, breaking windows, and the electricity was cut off. The family was forced to flee to Tehran. When returned to Shiraz a month later, they learned their house had been confiscated.

Simin Saberi was arrested in her house on the night of November 23rd, 1982, and along with her “books” she was taken to the IRGC detention center in Shiraz. A few months later she was transferred to Adel Abad prison in Shiraz.

She wrote several letters from prison. She said that she was doing well and repeatedly asked the family to “put aside grief and pray for her.”

Olya Rouhizadegan, a fellow prisoner of the executed Baha’i women, says that Simin in prison “was a symbol of love and affection and courageously with perseverance, lifted everyone’s spirit.” Her mother is quoted as saying that in one of their last meetings, her daughter said, “Don’t expect me to get out of here.”

Following a visit with their families, Simin and nine other Baha’i women were sequestered from other prisoners. They were hanged hours later.

Eshraghi Family, Execution of Mother and Daughter Two Days After Execution of Father

Roya Eshraqi and her mother Ezzat Janami were executed on June 18, 1983. Roya’s father, Enayatullah Eshraqi, had been executed two days earlier. Roya was 23 years old at the time of her execution.

On Monday, November 29, 1982, guards arrested three members at their house in Shiraz. That night a wave of arrests of Baha’i citizens was carried out, with at least 45 other Baha’is were arrested in this city.

Despite the experience of being arrested by the IRGC, the Eshraghi family did not leave their country, nor the city of Shiraz.

On January 17, after weeks of interrogation, a bail of one million tomans was set for Enayatullah Eshraghi. He refused to be released without his family, saying, “We have been arrested together and we must be released together. If the bail is set, we only have one house and that’s for the three of us. I don’t want freedom without them.”

Enayatullah Eshraqi along with Abdul Hossein Azadi, Bahram Afnan, Koorosh Haqbein, Jamshid Siavashi and Bahram Yaldai were executed on Thursday, June 18, 1983. None were allowed legal counsel, there are no available records of the trial proceedings, and their families were not informed of their executions.

Rosita Eshraghi, Roya Eshraghi’s sister, met her mother and sister on informed them about her father’s execution. Following the visit, Roya and her mother, along with 8 other Baha’i women, were not transferred from the meeting hall back to the prison cell. It is not known at what time between Saturday evening and Sunday morning they were hanged.

It was when the Eshraghi family went to the morgue to retrieve the body of Enayatullah Eshraqi, they learned about the execution of their mother and sister along with the other women.

Rosita Eshraghi wrote about the burial of the bodies of the ten women: “It was around noon time when they took the bodies to the Baha’i cemetery in an ambulance and dropped the bodies with the same clothes that they had on in the graves that were already prepared. After that, they rearranged the surface so that no one would know the boundaries of the graves, the locations of the graves, which grave belonged to whom.”

Disrespecting the Corpses and Destroying the Graves

In addition to the persecution of living Baha’is, those who had come to power following the victory of the Islamic Revolution continued their persecution through systematic destruction of many Baha’i cemeteries throughout Iran, digging up graves and destroying headstones with loaders and bulldozers. Baha’is experienced may difficulties in trying to find resting places for their deceased loved ones.

The Shiraz Baha’i Cemetery, in which the ten Baha’i women executed June 18, 1983, had been buried, was confiscated in by authorities in 1983. Thirty years later it was destroyed. The Fajr cultural and sports center for members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps was built on the site. The bodies of about 1,000 Baha’is were buried in this cemetery.

In 1981, Tehran’s Baha’i cemetery, known as Golestan Javid, was confiscated. Ten years later, it was also destroyed and the Khavaran Cultural and Art Center was built on the site. This had been the burial place of more than fifteen thousand Baha’is.

This hatred of the Shiite spiritual leaders was not limited to the Baha’is. It expanded to the gradual destruction of areas of Behesht Zahra, which belong to the political opponents of the government, as well as the destruction of the Khavaran cemetery belonging to the 1988 massacre. They continue this hatred to this day from stealing the bodies and secretly burying them to the destruction of the graves and symbols of the protesters killed in the protests of 2017-2018, 2019-2020 and 2022.

This practice of desecration, that has been repeated many times in the four decades since the Islamic Regime took control, has demonstrated the complete lack of respect sensitivity towards their opponents.

In the history of Shiite Iran, the evidence of these kinds of destructions can be traced back to Shah Ismail Safavi, who exhumed the ancestors of the Sunni rivals and burned their bodies under the pretext of revenge for the death of his father, and the death and burial of Ahmad Kasravi, a historian and writer by the devotees of Islam.

Amirhoushang Eftekharirad, a philosophy researcher, told BBC Persian about the view of death, the search and the afterlife in the Shia worldview: “The metaphysics of death and the body in Shia literature is no less than the verses of the Qur’an. One of the characteristics of these hadiths is the special treatment of the body and its punishment even after death. The dead body and everything related to it, from the tombstone and grave to the burial method and mourning ceremony for someone who has committed a mistake from the point of view of Sharia, should be completely different from a Muslim dead body.”

According to him, it is the result of such a view that causes “The Islamic Republic, which is a religious government, buries its opponents in mass graves at night secretly, break the gravestones and condemn their bodies and even their families.”

Leave a Reply