Source: iranwire.com

Kian Sabeti

“Akhtar was a gentle and patient young woman. She was always by herself. Whenever her cellmates were absorbed in conversation, she left the cell, walked along the bars or prayed. Nobody could imagine that one day they would kill Akhtar as well.”

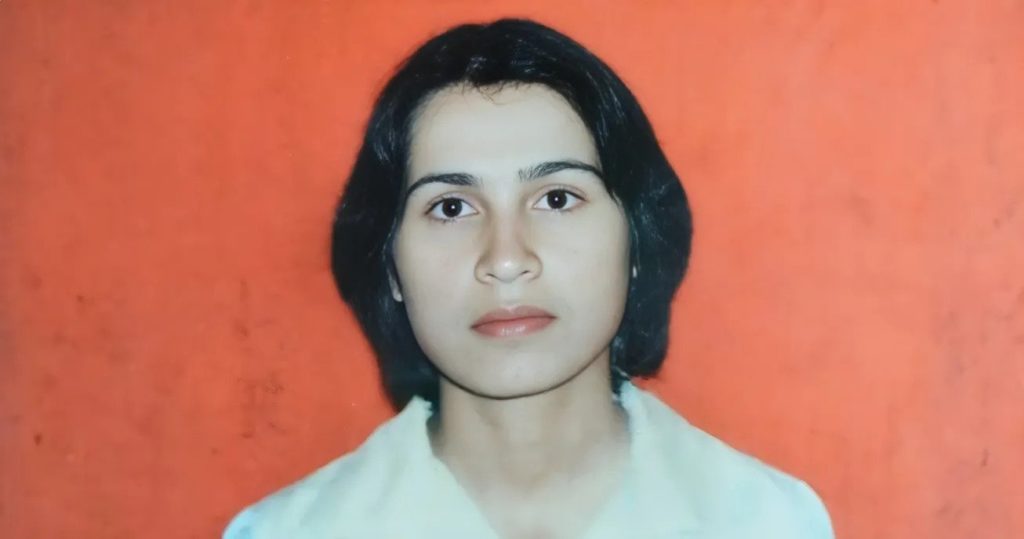

This is how Akhtar Sabet is described in the book Golden Destination, the stories of a number of Baha’is executed in Shiraz in the early 1980s, shortly after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. On June 18, 1983, Akhtar and nine other Baha’i women were hanged because of their faith. She was 25 when she was executed. Government agents buried them in the Shiraz Baha’i cemetery without performing Baha’i religious rites and without the presence of their families. A year later the government confiscated the cemetery. In 2014, the cemetery was completely demolished to build a cultural and sports center for the Revolutionary Guards.

Who was Akhtar Sabet Sarvestani?

Akhtar Sabet Sarvestani was born to a Baha’i family in Sarvestan in Fars province. She went to school in that city until the ninth grade and then went to Shiraz to continue her education although the family stayed in Sarvestan. She returned after receiving her high school diploma, but after passing the entrance exam of Shiraz University’s School of Nursing, she once again moved to Shiraz.

She completed her studies for an associate degree in nursing. The early 1980s start of the so-called “cultural revolution” and the “Islamization” of the universities in Iran meant that Akhtar and other Baha’i students were expelled from the university – which refused to give her the associate degree which she had earned.

Leaving Sarvestan as Their Homes Burned

On November 18, 1978, as Muslims marked the anniversary of the Eid al-Ghadir, a significant Muslim holiday, a group provoked by clerics in the city attacked and torched Baha’i businesses. Sabet’s family and many other Baha’is escaped to Shiraz from Sarvestan, under cover of the night, but Akhtar Sabet did not join her family.

According to a relative, she said that she was not afraid and that she was confident that the people who had carried out the attack would realize their mistake about the Baha’is and then the situation in the city would become calm and return to normal. The next day, however, attacks intensified and groups of people attacked the Baha’is’ home and destroyed whatever belong to them. That night Akhtar was forced to join her family in Shiraz.

Nursing Sick Children and Arrest

In 1980, Akhtar was hired by Saadi Hospital in Shiraz for its children’s ward and she worked at this hospital until she was arrested. “Akhtar loved nursing and she was happy that she could play a role in treating and curing the patients,” says the relative. “She oftentimes filled in for her friends or, if there was a party or a wedding, she voluntarily remained at work so that other nurses could go to the party. She was a cheerful girl but was very disciplined in her work. She never allowed her private life to interfere with her work. For example, she never used the hospital’s phone because she believed that it was for managing patients’ affairs, not the personal affairs of employees. She would not even give her family the address of where she was working and said that when she was working she must concentrate her attention on taking care of patients and any interaction with the outside world, be it very small, could distract her attention from the patients who were assigned to her care.”

On October 23, 1982, agents of the Revolutionary Guards arrested 38 Baha’is in Shiraz with arrest warrants from the prosecutor and took them to the detention center of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC). Akhtar was not among the detainees that day. But her family knew that she would be arrested too because she tutored Baha’i children and several such tutors had already been arrested. They asked her to escape to another area for a time, but she said: “Where can I go without making trouble for others? I remain here and whatever happens is God’s will.”

Most of the time, Akhtar lived with her sister. The architecture of their home was traditional: a courtyard with four rooms on its sides. At 9pm on October 29, government agents entered the house, searched every room, and arrested Akhtar. Her uncle’s wife pleaded with the agents to allow Akhtar to present herself the next morning, because her parents were not there at the time, but they refused and said: “You want to forge a passport for her so she can escape!”. Her uncle’s wife answered: “Do you think she would live with such limited means and in such a house if she could afford a forged passport?”

Akhtar Sabet in Detention

At first, like other Baha’is, Akhtar was taken to the IRGC’s detention center in Shiraz. She was kept in solitary confinement for 14 days before she was transferred to the women’s area of the detention center. Then, on November 29, Akhtar and other Baha’i detainees were transferred to Adel Abad Prison. On the same day, 40 other Baha’is were arrested in Shiraz and place in the detention center.

The center was where interrogations were conducted. Interrogations were focused on two goals: getting the names of other Baha’is and forcing the detainees to renounce their faith. To achieve these goals, the interrogators insulted, humiliated, threatened and sometimes even physically punished the detainees. In Adel Abad Prison every government agent, from the judge to the examining magistrate, the warden and even the guards, pressured the Baha’is to renounce their beliefs and convert to Islam.

The trials of the Baha’is followed the same pattern. They were taken from Adel Abad Prison to the courthouse and kept waiting in a bathroom until Hojatolislam Ghazaei, head of the Shiraz Revolutionary Court and the judge, called their names. When the detainee entered the courtroom, the judge first read the indictment, then shouted insults and told the defendant that she had only two choices: conversion to Islam or the death sentence.

When the defendant refused to renounce her faith, she was ejected from of the courtroom under a barrage of curses and foul language. The trials lasted just a few minutes and the defendants were not represented by a defense lawyer, not even a court-appointed one.

Remembering Akhtar Sabet in Prison

We do not know much about the days that Akhtar spent in Adel Abad Prison before her execution. Her cellmates remember her as a kind and selfless girl who did not speak much, was shy and spent most of her time alone. When a cellmate named Mahboubeh was punished with lashings, Akhtar regularly put Vaseline on her back and took care of her. Or she insisted on washing the clothes of Tuba Zaerpour who had been brutally lashed and suffered from excruciating headaches. Whoever fell ill, Akhtar took care of her and would sit next to her bed until morning.

“Akhtar was always ready to do anything,” remembers a cellmate. “She always sat at the end of the dining table, next to the door, and the moment that something was needed she would go to other cells and bring back what was needed. One day we decided to sit Akhtar at the head of the table, to show her our respect, and so that she would not leave the table all the time. However, just a few minutes after we had started eating, Akhtar said ‘Pardon me,’ jumped up, went to the other end of the table, and then brought salt from another cell. Apparently somebody had said that the food needed salt!”

Akhtar’s Family

Akhtar loved her family. They were not rich, and Akhtar helped them by giving some of her salary to her parents. While in prison, she was unhappy because she could not help them.

“I decided to write you a letter and thank you for everything that you have done for me,” she wrote in a letter to her family from prison. “My noble father: I don’t know with what words I can express my gratitude for all you have done for me throughout the years and I hope you will accept these few words that I am offering. My kind mother: I don’t how I can thank you for the hard work that you have done for me. The only thing that I want from you (and from you all) is to pray for us. My dear sister, I am grateful to you, too, for everything that you did for me in the past few years. However, I hope that my niece and my brothers will forgive my temper tantrums. I have not been able to properly thank you all in this letter but, I repeat, I am grateful to you all.”

“Repent or Die!”

On June 12, 1983, Hojatolislam Zia Mir-Emadi, the Shiraz Revolutionary prosecutor, accompanied by Torabpour, the chief warden of the prison, and a few guards, went to prison and told imprisoned Baha’i women that they had all been sentenced to death but that he had not yet signed the verdicts. Then he told Torabpour: “Have four repentance sessions for them. Release them if they repent; otherwise, carry out the sentences.”

On June 14, Akhtar Sabet and five other Baha’i women were summoned. Each were given a form which asked them: “Are you ready to renounce your beliefs?” And at the bottom of the form it said: “Do you confirm and sign your answer four times?”

All six Baha’i women answered “No” and signed the form. However, nobody believed that Akhtar would be executed. Even her cellmate believed that they had just wanted to intimidate her.

The Executions

On June 16, 1983, six Baha’i men who had refused to “repent” and convert to Islam were executed in Shiraz. In the evening of June 18, the Baha’i women in prison were allowed to meet their families and it was then that they learned about the executions of the men. None of them knew that this would also be the last time that they saw their families.

Olya Roohizadegan, one of Akhtar Sabet’s fellow inmates, wrote in her memoirs: “On Sunday, June 18, Akhtar Sabet’s sister came to the prison to visit her. In the afternoon, a group of 10 Baha’i women was brought to the phone booth accompanied by male and female guards. Akhtar told her sister: ‘Ayatollah Ghazaei and Mir-Emadi, the Revolutionary Prosecutor, have threatened us for the last time, [and said] that if we do not repent from our religion, they will execute us all. I ask you to persevere and endure. Pray for us so that we can remain steadfast in our faith for the last minutes of our lives. Say goodbye to all our family, friends and relatives on our behalf.”

After the visits, as the prisoners were returning to their ward, the chief warden, who was standing by the door, called the names of 10 of them, including Akhtar Sabet, separating them from the others and taking them away. While this was going on, the families of these Baha’i women were returning home without an inkling of what was going to happen.

On the morning of June 19, 1983, the families learned that their loved ones had been hanged the night before and that the bodies lay in the morgue. None of these 10 women were allowed to write a will. They were hung one by one as the next one watched.

Akhtar Sabet Sarvestani was 25 years old at the time of her execution. The guards let her family see her body, but they refused to let the family take the body for burial. Her place of burial remains unknown.

Leave a Reply