Source: qz.com

WRITTEN BY Neha Thirani Bagri @NehaNotes

Marjan Davoudi was 19 years old when she was told that she was not human.

Davoudi, now 56, had been studying math at the National University in Tehran when the Islamic revolution began in 1979. All the universities in Iran were closed for about a year while the revolutionaries overhauled the educational system to reflect Islamic ideals. When they reopened, the students were given an application for readmission.

This time, they were asked to list their religion.

Davoudi identified herself as a member of the Baha’i faith, and was expelled. An administrator at the university, who knew Davoudi personally, offered to get her an appointment with the dean to appeal the expulsion.

“I told him that I’m Baha’i and that I was expelled from the university only because of this. I talked about human rights,” says Davoudi. “He said ‘you’re not human, how dare you talk about human rights?’ He said being a Baha’i is in fact a crime and that I should be happy that this was the least that was going to happen to me.”

There are no good numbers for how many Baha’i were living in Iran at the time of the Islamic Revolution; there are an estimated 300,000 Baha’i left today, making them still by far Iran’s largest religious minority. The Baha’i faith was founded in 1844 in the Iranian city of Shiraz, when a man called the Báb announced he was “bearer of a message destined to transform humanity’s spiritual life,” and that there would be a second messenger from God that would arrive to lay out the message in detail. In 1863, a man called Bahá’u’lláh was declared to be the messenger foretold by Báb and began to preach a message of unity across the world’s faiths. Muslims in the country saw the faith as heresy and an insult to the teaching of Islam; Bahá’u’lláh’s followers were attacked and he was forced into exile. Through most of the 20th century, Baha’is were periodically attacked in Iran but the monarchs ruling the country tolerated the faith for the most part. After the Islamic revolution, these attacks accelerated.

Even in 2017, Baha’i are viewed as heretics in Iran and discriminated against. But in the decade following the revolution, it was especially awful—perversely, what the dean of the National University in Tehran had told Davoudi turned out to be true. Expulsion was nothing compared to the torture and imprisonment of hundreds of Bahai’s were tortured and imprisoned, or to the tens of thousands who lost their jobs because of their religious beliefs. Bahai’s had their homes and belongings confiscated and were denied passports to leave the country. And over 200 Baha’is were killed. One was Davoudi’s father.

Through it all, though, Davoudi did not give up her drive to learn. Nor did dozens of other young Iranian Baha’is. At first they mostly took correspondence courses, and met, clandestinely, to share materials and information. Then, about seven years after the revolution, the international Baha’i community realized: if Baha’i students in Iran couldn’t go to Iranian universities, they would have to start their own. Eventually, it became the Baha’i Institute of Higher Education (BIHE)—still informal, still illegal, but now with a global network of graduates, professors, and and international supporters.

Today, BIHE graduates have been admitted to over 80 different graduate programs in North America, Europe, Australia, and India. They’ve gone on to some of the best schools in the world, including Yale, Berkeley, Columbia University, University of Chicago, and Johns Hopkins.

The founding of the informal university

In the years after the revolution, Davoudi and other young Baha’is tried to keep their studies going by enrolling in correspondence courses with foreign universities.

Davoudi remembers poring over her English dictionary, preparing for the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) exam. When she passed, she enrolled in a correspondence program for general studies at Indiana University-Bloomington.

Studying by correspondence had its challenges. The government was monitoring the Baha’i community, and would often intercept and confiscate textbooks sent by mail. Those who were able to get textbooks would make copies of the relevant pages and share with other students. Davoudi remembers the thrill of seeing an original biology textbook—with color pictures, even! But soon, the Iranian government discovered that Baha’is had found a way to work around the mail problem, and began to raid homes, confiscating study materials and arresting those enabling the program.

“Even as a student you were in danger; it felt like a crime all the time,” says Davoudi. “You are sitting there just studying math or physics and you don’t know if you are going to be arrested for this or not.”

The Baha’i community was in an interesting position. Baha’i students were unable to enroll in university—and Baha’i professors were expelled from university and found themselves without jobs. In 1987, they decide to bring together that unused supply and unfilled demand, starting their own informal university: the BIHE.

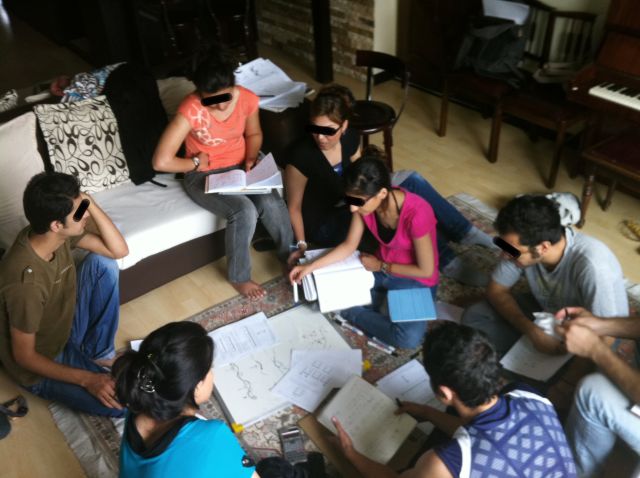

BIHE began as a mix of in-person and correspondence courses, the latter of which moved online once internet became easily accessible in Iran. Students now interact with professors over videoconference and submit class assignments online. The classes that do take place in person happen in clandestine locations, like the living rooms and basements of other supportive Baha’is in Tehran. Students come to the capital from all over Iran, meet with their professors and peers for a few intense days of instruction, and then disperse to continue their studies.

The institute has gradually expanded its course offerings and now offers a wide range of programs in the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. There are 18 undergraduate four-year degree programs and 15 graduate level programs. About 1,000 students now apply to the institute each year; BIHE accepts about 450.

Building a faculty of volunteers

In the beginning, the institute relied on faculty fired from teaching positions in Iranian universities. But three decades on, one of the institute’s biggest resources are its former students, who often return to the institute to volunteer as teaching assistants, faculty, or administrators, even while working elsewhere.

Saman Mobasher, 35, grew up in a Baha’i family in Tehran and was denied access to Iranian universities after he finished high school. BIHE was his only option and in his first few weeks enrolled as a student at the institute he was disappointed with the facilities available to him.

“It was kind of a blow for me at first because I was very passionate about my education,” says Mobasher. “When I saw that BIHE was a way for the Baha’i community in Iran to respond in a peaceful and productive way to all the restrictions and suppression that are placed on them, my studies took on a deeper significance. I was obtaining a higher education, but I was also part of a collective action of resilience in the face of oppression.”

At 26, he graduated from the psychology program at BIHE and began to work as a teaching assistant. In 2007, he went to England and completed a masters in social and organizational psychology at Exeter University. Upon his return to Iran in 2009 he began to teach psychology at BIHE, and later became head of the program. Though he moved away from Iran in 2015 and is now based in the US, he continues to teach a distance course at BIHE.

Others BIHE students had similar trajectories. Niknaz Aftahi went from BIHE to the University of California-Berkeley, where she studied architecture. She now teaches online architecture courses for BIHE. “Sometime all you want is access to an architecture book, access to a physics solution, but you don’t have it and it’s so frustrating,” Aftahi says. “I have experienced that and so now I really want to help.” Aftahi’s husband, who also studied at BIHE briefly, teaches computer science to students back in Iran.

Davoudi was eventually able to leave Iran when the government loosened up the passport restrictions for Baha’is. She travelled to the US and enrolled in graduate school at Indiana University, the same school with which she had taken undergraduate correspondence classes. As soon as she received her doctorate in psychology, she began to teach at BIHE online. Davoudi, now a clinical psychologist based in the US, considers teaching at BIHE one of the most rewarding parts of her professional life

Today, the institute has about 700 faculty members, including the volunteer professors teaching online courses from around the world.

Though teaching at BIHE is considered illegal by the Iranian government, many non-Baha’is within Iran have volunteered to help. Mobasher recalls a time when a professor from a well-known university in Iran got wind of the situation, and volunteered to teach any course they needed. “It was dangerous for him,” says Mobasher. “If the government found out that he was helping BIHE he would probably be in trouble. He was not a Baha’i. I considered that a precious achievement.”

To survive as an underground institute in Iran requires more than just a faculty. The Baha’i community’s members help to sustain the institute, often at great personal cost.

Families that host classes in their homes are putting their livelihoods and even lives in danger. But they continue to chip in. “Some of these families have little children, and the kids learn to be quiet when there is an ongoing class in the living room,” says Aftahi. “Sometimes neighbors would lend chairs, dads would give rides, and moms would cook. The whole community is trying to make it work.

While students pay a minimal fee for attending the institute, costs are low because the teaching is voluntary and there is no university campus. Even then, students unable to pay are allowed to study for free, and the rest of the cost is borne by the Baha’i community.

How to learn when learning can get you killed

While students in most universities suffer from the stress of being unprepared for examinations or having overdue assignments, students at BIHE stress about getting arrested.

Aftahi recalls the caution they would have to exercise constantly. When going to classes in someone’s living room or basement, students would try to avoid attracting attention. “We would go one by one,” says Aftahi, “so that neighbors would not see a group of people going to someone’s house at the same time.”

Once inside, they would have to be vigilant. “Most of the time there is someone looking, at the door. He would be reading the newspaper or doing something but it was obvious that he was watching us,” says Aftahi. Likely, it was a government agent, watching and reporting on the group.

The Iranian government’s interest in BIHE waxes and wanes; when there’s an uptick in threats and arrests, classes are held mostly online and the institute is less likely to accept volunteer faculty. As a result, it’s taken some students—depending on when they’ve enrolled—several more years than is typical to earn the credits required for an undergraduate degree.

Over the 30 years the institute has been functioning, the Iranian government has periodically carried out waves of raids, mass arrests, and confiscations of books, laptops, and lab equipment. In the last major wave of arrests, about five years ago, the government jailed 20 people from BIHE’s administration, faculty, and student body, and interrogated over a 100, says Mobasher, who was head of BIHE’s psychology program at the time.

Once inside, they would have to be vigilant. “Most of the time there is someone looking, at the door. He would be reading the newspaper or doing something but it was obvious that he was watching us,” says Aftahi. Likely, it was a government agent, watching and reporting on the group.

The Iranian government’s interest in BIHE waxes and wanes; when there’s an uptick in threats and arrests, classes are held mostly online and the institute is less likely to accept volunteer faculty. As a result, it’s taken some students—depending on when they’ve enrolled—several more years than is typical to earn the credits required for an undergraduate degree.

Over the 30 years the institute has been functioning, the Iranian government has periodically carried out waves of raids, mass arrests, and confiscations of books, laptops, and lab equipment. In the last major wave of arrests, about five years ago, the government jailed 20 people from BIHE’s administration, faculty, and student body, and interrogated over a 100, says Mobasher, who was head of BIHE’s psychology program at the time.

At one point, Mobasher got a call from Iran’s intelligence service asking him to come to a specific address, where he was interrogated for over two hours. They told him to draw an organizational chart of BIHE and provide the names of all the students, instructors, and administrators. He refused to give the students’ names, but knew that they already had the names of all the instructors and administrators and complied with that part of the demand.

The man interrogating Mobasher was young, and the psychology professor realized that he probably had many misconceptions about the Baha’is community. Likely, the interrogator had been indoctrinated to believe the Baha’i were involved in espionage, leaking information about Iran to hostile countries. “I told him ‘How is that possible? You are not even allowing Baha’is to open a bakery, let alone getting government jobs that would give them access to important information,’” says Mobasher

The young man then said he was worried that the head of the Baha’i community in Israel might order Baha’is in Iran to arm themselves and fight against the government. When he learned that Baha’is are forbidden by their religion to carry a gun or harm anyone, he was surprised.

“That is what [Iranian intelligence agents] are told,” says Mobasher. “Because they need some excuse—otherwise they would wonder why should they arrest these peaceful people just for being in their houses and studying chemistry, psychology, and sociology.”

Mobasher and the interrogator spoke about the Baha’i faith and history; later the young man asked Mobasher about life in England, and the differences between Westerners and Iranians. Though Mobasher was interrogated a second time for half an hour, he was not arrested.

Through the raids and arrests the institute has managed to stay open for three decades. Aftahi recalls one raid in May 2011 when, while government officials were arresting professors in one location, classes continued on elsewhere. As one physics professor was being taken into government custody, he asked his teaching assistant—Aftahi’s friend—to continue the class as usual.

“Always people take over,” says Aftahi. “When someone is arrested, someone else comes and takes over.” Recently, she says, the dean of BIHE was arrested, but others stepped up to cover the most essential tasks. One is to make sure that the institute’s website stays functional. “The internet is pretty slow in Iran generally, and the BIHE website is continuously hacked by the government,” says Aftahi. “But they are keeping up the website and doing a great job.”

Even under these stressful conditions, BIHE students strive for a semblance of normalcy. “The students are facing challenges that ordinary students would not face, and therefore we have to accommodate them,” says Behrooz Sabet, who has been teaching online, designing curriculum, and advising students at BIHE since 1990. But at the same time, Sabet—a Baha’i who left Iran after the revolution and got his doctorate at the State University of New York at Buffalo—says that despite the extreme conditions they face, his students communicate their problems more or less the same way as students anywhere in the world. “They say ‘sorry for not being able to send my assignment, I’m going to do that in the next few days,’” says Sabet. “They would not come to us and say ‘oh my god I am under so much pressure because of the situation of Baha’is in Iran or because my father was in prison.’”

The oppression of Baha’is in Iran doesn’t come up; course discussions are purely academic. “It’s not a normal teaching environment,” says Sabet. “But we try our best to make it a normal learning process.

The struggle to gain recognition outside Iran

The Iranian government does not recognize any BIHE degrees, and refuses to recognize graduate degrees earned by BIHE graduates at universities outside the country—effectively making BIHE enrollment a scarlet letter in Iran. Yet, gradually, BIHE has been able to ensure that universities outside Iran accept students from the institute and recognize their qualifications.

When Aftahi completed her undergraduate architecture course at BIHE in 2010, she moved to the US as a refugee and started the application process for grad school. She found it daunting because of the logical gymnastics required to explain her background. Aftahi had to explain that BIHE is not recognized within Iran because of religious discrimination—one barely ever discussed in the US—and not a matter of the academic standards of the institute. Aftahi was eventually admitted to the architecture department at the College of Environmental Design at UC-Berkeley, but still had to convince the admissions office to accept her transcripts. That wasn’t all that simple, since BIHE cannot give out an official degree, only a certificate listing the courses the student has completed.

Diane Hill, then assistant dean for academic affairs at Berkeley, recalls researching the human rights situation of Baha’is in Iran after hearing about Aftahi’s case. She brought the case to the then dean of the graduate division, Andrew Szeri. One of the requirements for graduate admission to any University of California campus is holding a bachelor’s degree from an accredited institution—so they would have to make an exception for BIHE.

“Since there was no opportunity whatsoever for Baha’is to gain a bachelor’s degree within Iran from an accredited institution, dean Szeri made the decision that the requirement would not be held against any student applying to be a student in graduate school at the University of California at Berkeley,” says Hill. Aftahi became the first BIHE student admitted to Berkeley.

Having faculty from universities across the world teach at BIHE has been helped it gain wider acceptance. Mobasher believes having letters of recommendation from BIHE professors who also taught at US universities was one of the reasons he was accepted to graduate school in England. The global faculty also establishes formal relationships with universities outside of Iran, creating more opportunities for BIHE students to get world-class post-graduate education.

These days, BIHE students are seen as able to hold their own with the most well-off and best-educated in the world; in the past decade, you could find BIHE grads on the campuses of Yale, Berkeley, Columbia, and more.

Attacking the core of a community

Discrimination against the Baha’i community within Iran continues even today. A September 2016 report on the state of human rights by the United Nations Secretary General found that the community is the most “severely persecuted religious minority” in Iran. Baha’is are routinely prohibited from holding peaceful gatherings, Baha’i owned businesses are often shut down or vandalized by the authorities, and Baha’is are still not given access to jobs in both the public and private sectors. The report also found that religious, judicial, and political leaders regularly make inflammatory comments that incite hatred against Baha’is. For example, in a May 2016 public sermon, Ayatollah Imami Kashini, a senior Iranian Muslim cleric, referred to the Baha’i as a “polluted sect” and “the enemy.”

Bahai’s continue to be denied access to universities. Many believe this is a strategic move, designed by the Iranian government to economically and socially disempower the community.

“The government is very adamant and persistent in diminishing this religious minority group in Iran,” says Mobasher. “They found that one of the best ways to do that is just depriving them of education so that this community gradually diminishes economically.”

In a September 2016 letter to Iranian president Hassan Rouhani, Bani Dugal, the principal representative of the Baha’i International Community, argued that the university ban had crippling economic consequences not only for the community but the country at large.

The best response, then, is to educate Baha’i youth at all costs.

“This was the most effective way to safeguard the continuity of the Baha’i community, because the goal of the government was basically to eliminate…culture and education in the Baha’i community and therefore let it die out by itself,” says Sabet. “[] is a unique educational experience, perhaps one of the unique experiences of higher education in the 20th century. [It’s] an example of resisting in a nonviolent, constructive way rather than resorting to violence or creating a disruption for the government.”

The 2016 UN report noted that Iranian authorities deny claims of discrimination and say that members of the Baha’i community have access to both education and jobs in the country. Shortly after, the Baha’i International Community issued a report in October 2016 claiming that representatives of the Iranian government have consistently misrepresented the way that the community is treated in Iran at the United Nations and other international forums.

“You know Baha’is are a minority in Iran, and…they are dealt [with] under the so-called citizen’s contract. Under this citizenship contract, they enjoy all the privileges of any citizen in Iran,” Mohammad Javad Larijani, the secretary of the Iran’s High Council for Human Rights, told the UN Human Rights Council on Oct. 31, 2014. “They have professors at universities. They have students at university. So they enjoy all the possibilities and privileges.”

According to Baha’i International Community, 90 Baha’is are currently imprisoned because of their religious beliefs, including seven Iranian Baha’i leaders. Since 2005, 860 Bahai’s have been arrested.

For those who study at BIHE, uncertainty and fear of arrest or other government retribution remains constant. “You have a physics class but you never know whether tomorrow your physics professor is going to be in the class or is going to be in prison,” says Aftahi. “They may come and shut down the place where your classes are held. You cannot plan for your future.”

Leave a Reply