Source: Persian Media Production

A note on the Mohammad Rasoulof film, “A Man of Integrity”

By Kian Sabeti

Translation by Iran Press Watch

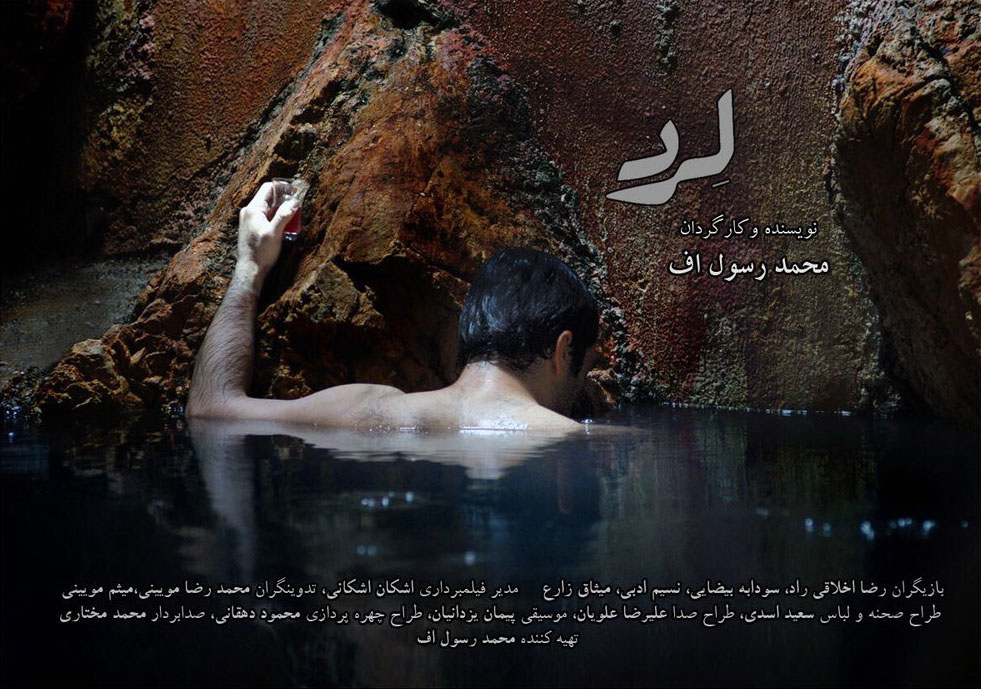

In May 2017, news spread on websites and in film media: “A Man of Integrity” (in Persian: “Lerd”), the sixth feature film of Mohammad Rasoulof, won the best film award in Cannes Film Festival in the category of “Un Certain Regard”.

The success of the film at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival promised a fruitful year for Iranian cinema; that made Iranian film lovers hopeful that Rasoulof’s “A Man of Integrity” would repeat the success of the 2016 film, Asghar Farhadi’s “The Salesman”, in the international arena. Unfortunately, on his return home, Rasoulof was unwelcomed by movie industry officials in Iran, and his film – which had originally been allowed – was banned. Upon his arrival at the airport, his passport and national ID card were confiscated, and he was summoned to the Attorney General’s office. His case was sent to court on charges of “propaganda against the regime” and “conspiracy and collusion against national security”.

Some of the websites and mass media in Iran accused his film of misrepresenting Iranian society and defending the Baha’i Faith. As was reported in the news, in his film a Baha’i child was expelled from school and banned from seeking education because of his religious beliefs. Consequently, the same youth commits suicide but is not allowed to be buried by his village authorities.

After Rasoulof’s interrogation and the ban on “A Man of Integrity”, more than seventeen thousand personalities signed a petition asking for the removal of restrictions against this Iranian filmmaker. Many Internationally known filmmakers such as, Atom Egoyan, Ken Loach, Michel Huntke , Costa-Gavras, Gerard Depardieu, and Isabelle Huppert are among the celebrities who signed this petition. Also, two hundred Iranian movie directors and artists in a letter asked president Hassan Rouhani to remove the travel ban for Rasoulof. This letter was signed by Massoud Kimiai, Asghar Farhadi, Dariush Mehrjui, Rakhshan Bani Etemad, Mehdi Fakhimzadeh, Leyla Hatami, Ali Mosaffa, Navid Mohammadzadeh, Mahnaz Afshar, Hediyeh Tehrani, and Amin Tarokh.

All these side stories made movie lovers eager to see “A Man of Integrity”. I am more or less familiar with Rasoulof’s works. I had seen two of his last films; “Goodbye”, released in 2011, and “Manuscripts Don’t Burn”, released in 2013. Although neither of the two was screened in Iran, they received many awards, as well as recognition for Iranian cinema. Among these are the award for Best Director for “Goodbye” at the Cannes Film Festival in the category of “Un Certain Regard”, and the International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI) award for “Manuscripts Don’t Burn”. Both films deal with issues in Iranian Society that were considered taboo at the time they were shot. To make movies with such themes required a lot of courage and audacity! “Goodbye” tells the story of a female lawyer whose license to practice law is revoked because she agreed to defend Human Right cases. She decides to emigrate, but as a woman faces many obstacles leaving the country. “Manuscripts Don’t Burn” explicitly narrates the story of the so-called “Serial Killings” – the assassination of Iranian intellectuals and writers in the late 90’s.

The subjects of these two films and the banning of Rasoulof’s latest work are testimonies to the fact that this brave Iranian filmmaker might have passed a red line and ignored the taboos in Iranian cinema. According to Mohammad Abdi, an Iranian film critic, “A Man of Integrity” is the last film of the trilogy Rasoulof made about current issues in recent Iranian Society; issues that many may not like to see depicted. Thus, his last three films were banned.

After two years of ban and refusal of screening, finally “A Man of Integrity” became accessible to all on Youtube. Enthusiastically, I watched it again. “A Man of Integrity” is the story of Reza, an expelled student from university, who moves to a village in northern Iran and away from the commotion of big cities to start a new quiet life with his wife and his child. He decides to open a fish breeding farm, and his wife works as a principal at the village school. However, despite seeking peace, he faces problems dealing with the corrupt local trading market. Trying to avoid corruption, he sees all doors closed in his face.

The plot is very sad and painful, but not so sad as to intimidate the viewer from seeing the film through. In my opinion, this film has a universal narrative. This is a story that reflects many people in different parts of the world who have been challenged by two options in dealing with corrupt authorities: escape or surrender. Can one live honestly in a corrupt society, or should you give in to make ends meet?

One of the most beautiful scenes of the film is when Reza, whose honor has been tainted by corruption, decides to bathe himself in the clear and clean water of a small lake on a mountain to cleanse himself from this filth and revive his conscious. The water, like mythical rivers and falls, steams in a cave in the middle of a mystical mountain. Apparently, it is only Reza who knows about this lake in the middle of the mountain; as if it were a temple, he retreats to it whenever he needs to cleanse this abomination and recognize himself again. These scenes are designed as if Anahita, the Goddess of the Waters and preserver of family values, were there to purify and protect Reza.

This filmmaker has made an excellent choice of a village for his film location. Villages in Iranian movies are symbols of purity, as they are far from cities, which represent modernity and aristocracy. But this is just an illusion to please viewers, and is far from the reality. The corruption in society, unhealthy competition, dirty income and profiting at any cost, and undermining others to succeed are the inevitable facts of an unsound society that, although attractive, can deceitfully keep any observer far from seeing the realities of the society.

For the first time in Iranian movies, “A Man of Integrity” has screened – no matter in how short and incomplete a way – the oppression of Baha’is in Iran without naming them. Of course, previously Akbar Khajooiee in his film “Mahya” (2007) in a dialog used the name “Baha’i” among other religions. In the sequence, Javid (played by Shahab Hosseini), faced with rejection of his marriage proposal, states:” You are not a Christian, a Jew, a Zoroastrian, or a Baha’i (are you?)”. In “A Man of Integrity” there is no direct mention of the name “Baha’i”; however, there are references, such as expelling a student for his religious beliefs, and later (after he commits suicide) refusal to bury him in cemeteries, that are clear indications that he is a Baha’i. There is a dialogue between the principal and a clerk at school that, although it relates to the Baha’i student, voices the concern of many, Rasoulof among them; concern that hypocrites, instead of treating the ailment, try to fix it with a pill, and instead of finding a solution, try to remove the problem.

Clerk: I have heard that if they give an ad in a public newspaper (renouncing their belief) their issue will be resolved.

Principal: Ad for what?

Clerk: That he is not a believer

Principal: Dear…, he knows that. Surely he does not want to.

Clerk: (but) Ma’am, it’s not a big deal to leave an ad in the papers….

Leave a Reply