Source: www.bbc.com

Translation by Iran Press Watch

Ivan Mohajer

“This year, when the results of the national exam were announced, the answer for me and my family was predictable, “Incomplete application.” Many of my friends had seen the same phrase. But I was upset by the reaction of many cyberspace users and even non-Baha’i friends and acquaintances who said: Why don’t you write Muslim in your application form to go to university?”

These are Samira’s words ‒ a young woman who has taken the national entrance exam for the first time and, like many Baha’i Candidates for university, has been subjected to systematic academic discrimination, as has been applied against several generations of Baha’is. (Samira’s name, like the others interviewed in this report, has been changed for her safety.)

Can Baha’is exercise their social rights, such as university education, employment in government offices, high-paying jobs, and other deprived rights, by concealing their beliefs?

Azadeh Rezvani is a Baha’i woman who says after all these years, she has never regretted standing by her beliefs:

“In June 1980, the principal of the school where I was teaching called me and asked me about my religious beliefs. In response, I told him that both you and the other school officials know what I believe. The school principal stated that if you do not publicly announce that you have left the “deviated sect”, we will have to expel you. A few months ago, a member of our family had been executed in Evin prison. I said that if I did that, I would be ashamed in front of that person. Even though I had only three years left until my retirement, I was fired, and after forty years of following up, my pension has never been paid.”

This year, with the announcement of the results of the entrance exam, Baha’i students realized that they were listed under “incomplete application”, and had been locked out and denied study in their chosen field.

A number of Baha’is during this period gave in to changing or concealing their beliefs, and apparently succeeded in gaining back their civic rights.

Ghodrat, who publicly announced his departure from the Baha’i faith in 1988 in one of the most widely circulated newspapers, says: “We were under a lot of pressure in those years. After a while, I saw that I had no other way but announcing that I was a Muslim, to protect the future of my wife and children, so I informed the company officials. But after a while, I was told that I could not just announce it secretly and that I should publicly announce it in one of the widely circulated newspapers, and, as they say, “recant”. I did this, but after a while, some officials came to me again and said that I should cooperate with them. They meant to give them as much information as I could about the Baha’is every now and then. Although I told them that I would no longer attend Baha’i meetings, they still insisted. Eventually I realized that they would regularly be asking me for something more, and that little by little I would have to harm my family and friends. So, I preferred to leave that company after 5 years. Of course, after that, my four children were able to attend university in the decades of the 1990s and 2000s, with no problems.”

The individuals who were asking Ghodrat for his cooperation were security officials, who contacted him from time to time. This experience shows that adherents who in the 1980s renounced their beliefs in order to maintain their job or social status were again and again faced with new forms of pressure and discrimination.

Ehsan, who had been in food distribution in the suburbs of Shiraz in the 1990s, had a different experience. After the Islamic Revolution and the expulsion of dissidents and religious minorities from administrative jobs, Ehsan resigned from his job before being fired and started in food distribution: “Fortunately, I was able to have a good job, and provide for a number of families as a result. And after a while, I was able to enhance my business. I didn’t speak much about my beliefs with anyone that I worked with, especially with the supermarket owners. However, after a while the supermarket owners in certain small towns did not buy from me, and little by little this happened in other cities as well. So much so that a good portion of my work stopped. After a brief follow-up, one of the owners of these supermarkets informed me through an intermediary that several “Hezbollah” people had come to his shop and advised him that it was better not to buy food from a Baha’I, or it would not end well for them.”

This caused Ehsan to give up distributing food, which is one of the banned jobs for all his religious community members, and take up other jobs. This method of using a secretive approach in economic restrictions against the followers of this religious minority was seen in various forms in the 1990s.

Ehsan says: “Many of my friends and acquaintances in Shiraz and other cities had similar experiences; after a while they realized that many potential business partners had refused to work with them due to threats and intimidation by certain individuals. “Some were able to continue their work, and some could not.”

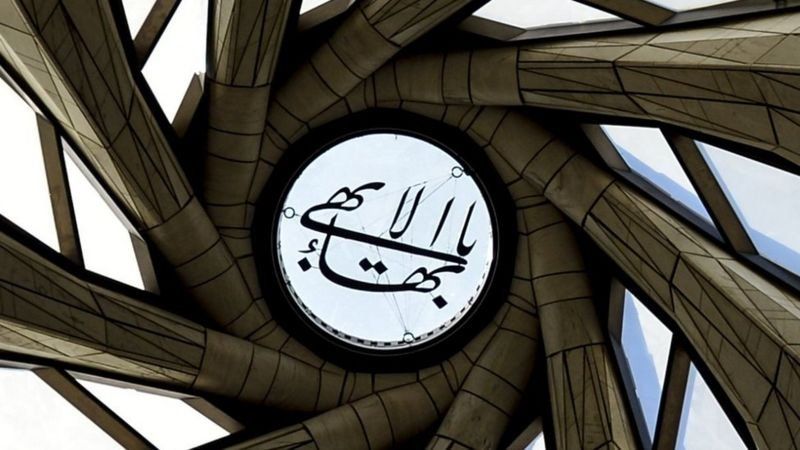

Distributing food is a forbidden occupation for Baha’is – The caption on the photo says: This business has been sealed and shut because of problems with the permits. For any follow-ups refer to the Office of Properties. There are legal ramifications associated with breaking a government seal.

Did the decade of the 2000s show any leniency?

In the early 2000s, the situation for Baha’is in Iran changed. With the change in the economic situation and the growth of private companies, in many employment questionnaires the religion question was removed or ignored by the human resources hiring officials of these companies. A similar change was made to the National Entrance Examination Questionnaire in 2004. The “Religion field” was changed to “Responding to Religious Knowledge questions,” raising hopes for a change in the process of discriminating against Baha’is, but the National Education and Assessment Organization in later years used the label “Incomplete Application” for many Baha’i student candidates, instead of announcing their score and the results of the educational field in which they had been accepted.

In the meantime, most of the students who had found a way to university were expelled. It seems that the National Education and Assessment Organization, together with the Ministry of Intelligence, had precise information on the details of their record in identification of Baha’is who had registered for the national entrance examination.

In this regard, Lava says: “In 2005, after I faced an incomplete application and could not go to a national university, I went to a Baha’i university, and studied urban development there.” At that time, the Baha’i University was concentrated in Tehran and I had to go to Tehran to study. Six months had passed since my student life in Tehran when I returned to Isfahan for my mid-term vacation. That was when my parents said that individuals had come to our house from the Ministry of Intelligence and asked about our work and the number of people in our family. In the same week, they had approached many other Baha’is and asked them the same questions. And finally, they said to my parents that “your daughter has not lived with you for some time” and inquired about her whereabouts. This meant that we had been under surveillance for a long time.”

Lava’s account relates to a directive issued by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei “urging relevant organizations to collect, in a highly secretive way, all available information about Baha’is.”

This memorandum, dated November 2005 and written by the General Staff of the Iranian Armed Forces, is directed to the Ministry of Intelligence, the Revolutionary Guard Corps, and the Law Enforcement Forces, and asks them to identify Baha’is and monitor their actions.

With this in mind, Iranian security agencies sought to identify and monitor Baha’is in order to prevent activities that would lead to their community’s growth and improvement in social status. But, were all Baha’is under the control of the Ministry of Intelligence and the security services?

On August 21, 1980, all members of the Baha’i National Spiritual Assembly, along with two of their associates, were arrested when armed men invaded, during a meeting of the spiritual assembly. They were never seen again by any of their family or friends.

Emad, who lives in Tehran, talks about his experience of protesting the results of the 2009 presidential election. He was active in a trading company at the time. He says: “I don’t know if it was the end of June 2009 or the beginning of July of that year when I got out of a taxi in Enghelab Square and wanted to go to the other side of the square.” There were a number of protesters on the east side of the square who rushed to my side after being attacked by the special guards. In the middle of all this, I was arrested by plainclothes agents and taken to a building near the square. Many were arrested and briefly questioned on their reasons for being present in the square. From my appearance in an office suit, holding a Samsonite brief case, it was clear that I was on my way to work. After checking my national ID, one of the plainclothes men approached me with a sarcastic smile and said, “So you’re a Baha’i too ‒ you’ll remain our guest for a while.” However, they released me two days later.”

Evidence of this kind reveals that after the issuance of the national identification card in Iran, the members of this religious minority in Iran were systematically monitored.

In the eyes of the official Iranian institutions, are only those who identify themselves as Baha’is and attend Baha’i meetings considered to be Baha’is? What is the scope of the security agencies’ oversight of these individuals?

Solmaz has a Baha’i mother and a Shi’ite father. She did not attend Baha’i Meetings and was not listed in Baha’i Administration records. But in 2013, after being accepted at Tehran University, she was barred from enrolling. After calling the head of the Ministry of Science, in the first year of Hassan Rouhani’s presidency, to return those deprived of their education to university, Solmaz went to the Ministry of Science with her father. Despite initial talks about the “mistakes made” by Mr. Noorbakhsh, the then director of the Student Selection of the Assessment Organization, they stated that Solmaz would have to “officially write that she has no intellectual or emotional connection with her mother’s beliefs” to be allowed to register.

Such an approach reveals that official institutions in Iran also consider those whose parents are Baha’is and who have been borne and raised by a Baha’i person are considered to be Baha’is and therefore subject to social exclusion.

Shiva’s experience confirms the same. She says: “In 2019, I applied for a passport. In the form I left the religion column blank so that there would be no problem, and the official responsible for reviewing the form wrote Islam in the religion column for me. As in the past, I did not object to this issue, because, despite the fact that my parents are Baha’is, I do not consider myself a Baha’i. I did the same thing when I got my national identification card and other items, and my name was not registered as a Baha’i in any official office. “But after taking a photo and printing my information at the police station, I was surprised to see that the system had printed “other / Baha’i” for my religion.”

Such experiences have taken place as the “other religions” option has been removed from the national identification card since last year; applicants are only authorized to declare one of the four official and recognized religions in the constitution of the Islamic Republic: Islam, Christianity, Judaism or Zoroastrianism, as their religious belief.

“Last year the Office of Properties sealed my father’s shop,” said Yashar, who has been acquainted with the Baha’i faith for several years, and has close ties to members of the religious community. My father went to the Office of Properties to follow up and was surprised to find that his shop had been closed and sealed because I was a Baha’i. “When he stated that he was a Shi’ite Muslim and that my beliefs had nothing to do with him, he heard this answer from the official: “You are lying. You have become a Baha’i like your son, but you do not say it.”

According to these experiences, it can be concluded that the scope and subsequent deprivation of this religious community in Iran has become much wider than previous definitions, and the official definition of the Islamic Republic of the largest non-Muslim religious minority in Iran has changed over several decades.

If in the beginning of the Islamic Republic, the expression of belief was the main criterion of sovereignty in identifying a Baha’i, and these citizens were forced to make one of two choices, so that they might be less discriminated against by departing from their previous beliefs, in recent years there is no longer a choice available in expression or non-expression of belief for these people, and mere familiar relationship is sufficient for this outcome.

Leave a Reply