Source: www.bbc.com

By Rozita Riazati

For 45 years, Iran’s most famous modern monument, the Azadi (Freedom) Tower in Tehran, has been the backdrop to every major news story coming out of the country.

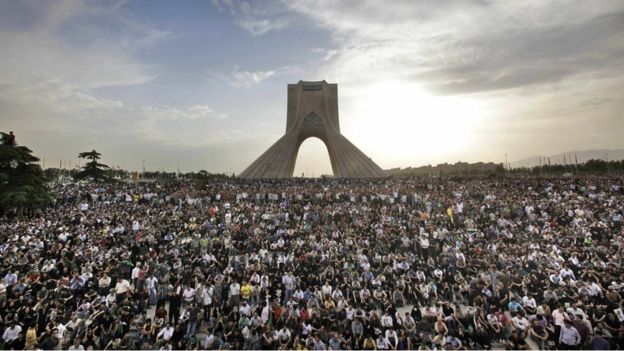

A plaza for celebrations, anniversaries, military parades and a gathering point for mass demonstrations, the 50m (165ft) tall tower has overlooked some of Iran’s most important political events.

The edifice was built in 1971, to represent a symbol of modernity and project the way forward for Iran.

Even at the time the project was finished, architect Hossein Amanat never expected that “it would become such an icon, so popular with the people of Iran”.

Originally named the King’s Memorial, or Shahyad, it was commissioned to mark 2,500 years of the Persian Empire, celebrating the richness of Persian history and culture.

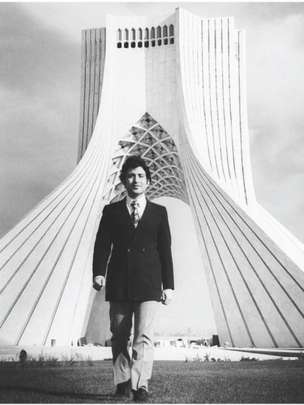

Hossein Amanat was a rising star in Iran’s architectural scene when, in 1966, he won a national competition to design the monument.

Hossein Amanat spoke to Witness on the BBC World Service – listen to his interview here.

_____________________________________________________________

Located in western Tehran, on the road from the city’s old international airport, the monument itself is made of white marble and is surrounded by a 50,000 sq m (540,000 sq ft) plaza, which is decorated with gardens, fountains, a museum and exhibition centre.

By the mid-1960s, Iran was already a major oil producing country, which led Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to embark on an ambitious programme of modernisation and industrialisation.

During this period, Iran’s modern art scene was simultaneously thriving. It was like “a mini renaissance”, says Mr Amanat.

Artists, poets and musicians were trying to create their own, original styles, distinctive from but also drawing inspiration from those in the West. Yet, they also had their eye on the traditional elements of Persian culture.

Mr Amanat says that the style of Shahyad was also a manifestation of this period – modern, yet very Persian, with aspects of both pre- and post-Islamic architecture.

The Azadi Tower took 30 months to complete and was inaugurated in the autumn of 1971.

For the occasion, the original Cyrus Cylinder, considered by many historians as the first bill of human rights, was borrowed from the British Museum for display in the museum of the tower.

It opened to the public on 14 January, 1972.

‘Symbol of Iran’

During the Iranian revolution of 1979, the plaza around the tower soon became a meeting place for protesters to gather; and its draw for those going public with dissent continues to this day.

Most recently, the mass demonstrations that followed the disputed presidential election of 2009 drew hundreds of thousands to Azadi Tower, where they demanded a recount of their votes.

Mr Amanat says that, of all the events that the tower has witnessed, this one was “memorable”.

For many Iranians living outside Iran, this surprising turn of events appeared to show a different side of the nation.

For Mr Amanat, the scenes were both personal and moving; he says the building was “like the embrace of a father, embracing all these people in front of it”.

Its historical pull, he believes, lies in the tower’s evolution as a “symbol of Iran”, an aesthetic icon of the capital that is both intensely Iranian and Islamic at the same time.

Many Iranians who left Iran during or after the revolution either fled or left the country by choice, for a plethora of different reasons; personal, political, religious or due to connections with the old regime.

Mr Amanat also left Iran just after the revolution and has not returned since.

Though the Azadi Tower has been damaged over time, Mr Amanat says he has never been personally approached or asked to help, even in an advisory role, with repairing it.

He now lives in Vancouver, Canada, where he has established a successful architecture firm and has designed buildings all over the world.

A member of the Bahai faith, Iran’s largest religious minority, Mr Amanat is also responsible for designing the Bahai World Centre, in Haifa, Israel.

Since the 1979 revolution, members of the Bahai community in Iran have been deprived of many of their civil rights and hundreds have been imprisoned and even executed for their beliefs.

Many Iranians living in the West, including Bahais, who wish to go back or visit their homeland, are fearful of doing so.

“I miss Iran, my country, very much, but at the moment I don’t feel I want to go there,” Mr Amanat says.

He feels the architecture of Iran is “unique” and regrets not seeing more of his country before he was in his early 30s, when he left.

He compensates for that with a special book that he fills with his own drawings of important historical Iranian buildings and places he visited during his childhood.

“I just dream about it… in my imagination I travel [there] many times.”

January 22, 2016 6:06 pm

Hossein Amanat is a legend not only in Iran, but in Canada, and the entire Baha’i World.