Source: iranwire.com

Kian Sabeti

The Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education has repeatedly pointed to a serious shortage of physicians and nurses in Iran over the last several years. The shortage became even more glaring after the coronavirus outbreak, with calls from the country’s medical bodies asking for volunteer physicians and nurses to serve in coronavirus care units in cities across Iran.

The shortage becomes even more glaring when we know that from the outset of the 1979 Islamic Revolution some Baha’i doctors have been executed solely for their beliefs, while the rest were dismissed from their positions for the same reason. Between 1979 and 1981, the new Islamic Republic government expelled all Baha’is working in healthcare in public hospitals or medical centers, regardless of their experience and expertise.

Baha’i youth admitted to medical university courses at the time were also deprived of their right to study and were forced to emigrate. Many of them have been successful in their new homes, becoming established medical professionals, and some have been involved in treating coronavirus patients. The irony is that they have done this not in their homelands but in the countries where the universities allowed them to study.

In a new series of reports, IranWire looks at what happened to Baha’i doctors and nurses after the revolution and in the 41 years that followed.

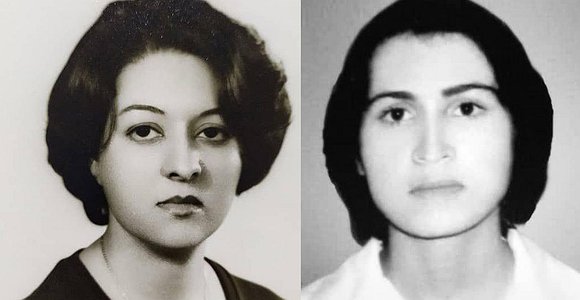

On the night of June 18, 1983, 10 Baha’i women, ranging from a 17-year-old girl to a 58-year-old mother, were hanged in Adel Abad Prison in Chogan Square in Shiraz on charges of belonging to the Baha’i faith. The bodies of the 10 women have never been returned to their families, and the location of their graves are unknown. During their lengthy and insulting interrogations, the authorities had given the women deadlines by which they had to abandon the Baha’i faith and become Muslims, according to reports from their fellow inmates. When the deadline arrived, none of the women signed the documents pledging that they would absolve themselves of their religion, and a judge and religious leader in Shiraz handed down death sentences to them. Among those executed were two Baha’i nurses: Akhtar Sabet Sarvestani and Tahereh Arjmandi Siavashi.

Akhtar Sabet

Akhtar Sabet was born in 1958 to a Baha’i family in the city of Sarvestan, Fars province. Sabet studied in the city until the ninth grade and then went to Shiraz to continue her education. After receiving her diploma, she returned to Sarvestan with her family, and then, after passing the exam at the Shiraz University Nursing Training Center, she returned to Shiraz. She graduated and continued her studies, but with the Cultural Revolution in 1980, she was forced to drop out of school and was expelled from the university along with other Baha’i students. Shiraz University refused to give her a post-graduate degree.

On November 18, 1978, as Muslims marked the anniversary of the Ghadir Khumm, when the Prophet Mohammad delivered a sermon at the Pond of Khumm, a group attacked Baha’i businesses and set them on fire, provoked by several clerics in the city. Sabet’s family and many other Baha’is traveled to Shiraz from Sarvestan at night, but Akhtar Sabet did not join her family. She planned to leave the city the next day and said she was not afraid and that she was confident that the people who had carried out the attack would realize their mistake about the Baha’is and that the situation in the city would become calm and return to normal. The next day, the attacks intensified, with groups of people attacking Baha’i homes and destroying their belongings. That night, Sabet had no choice but to join her family in Shiraz.

Sabet was employed at Sadi Hospital in Shiraz in 1980, where she worked in the pediatric department until she was arrested. “Akhtar was interested in nursing and was very happy to be involved in helping the recovery and treatment of patients,” said one of her relatives. “She often went to work instead of to her friends’, or if it was a wedding or a party of one of her colleagues, she always volunteered to work so that the rest of the nurses could go to the party. She was a happy girl, but very disciplined and bound by the principles of work and never let her home life interfere with her work. For example, during work, she never used the hospital phone because she believed it was for patients and not for employees’ personal use. She did not tell her family where she was working, and said that when she was working in the hospital, she should focus all her efforts on treating patients, and that even a little contact with the environment outside the hospital could have an impact on and distract her attention away from the patients she was treating.”

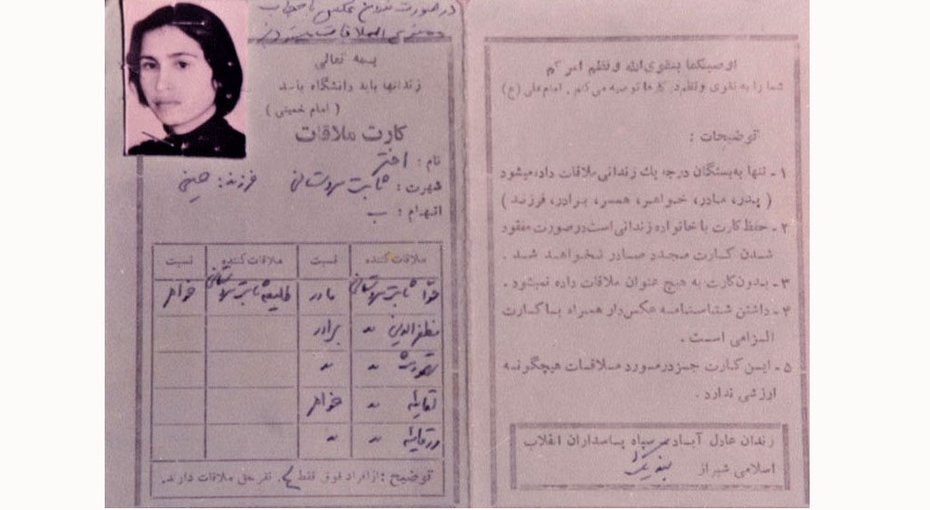

Akhtar Sabet was arrested on October 23, 1982 at her home in Shiraz. On that day, 45 Baha’i citizens in total were arrested in Shiraz. The detainees were transferred to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) Detention Center and interrogated at the same location. A number of Baha’is in Shiraz who were imprisoned at the time have described the use of physical and mental torture on prisoners to force them to convert to Islam.

Sabet was transferred from the IRGC Detention Center to Shiraz’s Adel Abad Prison three days later, and was detained until June 18, 1983, when she was executed.

Ruhi Olyazadegan, one of Akhtar Sabet’s fellow inmates, wrote in her memoirs:

“On Sunday, June 18, Akhtar Sabet’s sister came to the prison to visit her. In the afternoon, a group of 10 Baha’i women was brought to the phone booth accompanied by male and female guards. Akhtar told her sister: ‘Ayatollah Ghazaei, the Mir-Emad Revolutionary Prosecutor, has threatened us for the last time, [and said] that if we do not absolve from our religion, they will all execute us. I ask you to persevere and endure. Pray for us so that we can remain steadfast in our faith for the last minutes of our lives. Say goodbye to all our family, friends and relatives on our behalf.”

Akhtar Sabet Sarvestani was 25 years old at the time of her execution. The guards let her family see her body, but they refused to let the family take the body for burial. Her place of burial is unknown.

Tahereh Arjomandi

Tahereh Arjomandi was born in 1953 to a Baha’i family in Tehran. Arjomandi completed her diploma with honors in Tehran and married Jamshid Siavashi a few months after graduating in 1972. After marriage, the Baha’i couple moved to the village of Chendar near Tehran.

Arjomandi registered to take the University of Tehran Faculty of Nursing exam. She was also told she was eligible to take an exam for students wanting to go abroad to study, and plans were made for her to travel to the United States. However, she decided to stay in Iran and continue her studies at the University of Tehran. She traveled to Tehran once or twice a week to attend classes.

After two years, the couple returned to Tehran and Arjomandi continued her studies. In 1976, she received a Bachelor’s degree in nursing and later moved to Yasouj with her husband. She worked as a nurse at a local hospital and her husband opened a small electrical appliance store. She was highly regarded during her service at Yasouj Hospital and was selected as “model nurse of the year.”

In late 1978, a group of people stormed her husband’s workplace, looting and destroying the shop. Subsequently, Tahereh Arjomandi was fired for following the Baha’i faith. A few days later, the city’s police chief, who knew her husband Jamshid Siavashi, told them on the phone that a group of local people, with the support and instigation of a cleric, were planning to storm their home at night and force them to convert to Islam after looting the place. He was told that the police would not intervene. In the middle of the night, the couple left for Shiraz to start a new life in that city.

Tahereh Arjomandi initially worked at Fatehinejad Hospital in Shiraz but was fired after a year, at a time when the Ministry of Health began to expel Baha’is on a large scale. She was then employed at the private Dr. Mir Hospital, where she worked for about three years. Her brother, who lived in the United States, insisted that Tahereh Arjomandi and her husband should immigrate to the United States to save their lives. But they refused, and she wrote to her brother that she wanted to serve her compatriots in her home country.

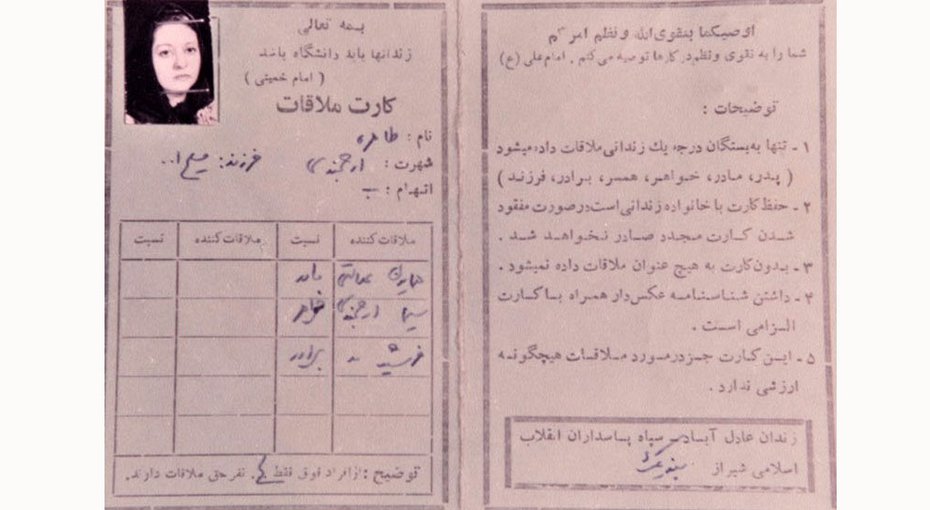

On October 23, 1982, security forces raided the couple’s home and arrested Jamshid Siavashi. Forty days later, on December 1, Tahereh Arjomandi was arrested. “During the 40 days that Tahereh was not detained, IRGC officers accompanied Jamshid to his home three times, and they inspected the whole house,” one of Arjomandi’s relatives said. “Jamshid was not in good physical condition. He was walking bent over and could not keep his balance; his feet were swollen, and he was not walking properly … The officers did not even allow them to speak, even to greet each other.”

According to another relative, they were a loving couple and their devotion to each other was well known. During Siavashi’s time in detention, Tahereh Arjomandi said, “I can’t live without Jamshid. Pray for me to be arrested so that I can go to Jamshid.” After she was arrested, when her family asked about her condition, she would say, “I’m glad they arrested me, because when I’m in the cell, I feel like Jamshid is behind one of these walls and I’m close to him.”

There have been no reports of Tahereh Arjomandi enduring physical torture to convert to Islam, but during visits from her family, she talked of psychological torture. For example, she was told that her husband had become Muslim and that she should do the same; other times she was told her husband had been tortured to death. “She was even taken to Jamshid’s interrogation room to witness the pressure on and torture of her husband,” the relative said.

On June 16, 1983, Jamshid Siavashi and five other Baha’is were executed. Alia Rouhizadegan, one of Tahereh Arjomandi’s fellow inmates, wrote: “On the same day that Jamshid was executed, Tahereh was taken to court to be notified of the ruling of the religious judge. When Tahereh returned, I asked her: What happened? Tahereh said, I used to think that they will only kill Jamshid, but now it has become clear that the judge has also sentenced me to death.”

Two days later, Tahereh Arjomandi Siavashi was hanged at the age of 30 along with nine other Baha’i women on charges of religious dissidence and following the Baha’i faith in Chogan Square in Shiraz. The bodies of those executed were not given to their families and the location of their graves is unknown.

April 22, 2020 6:11 pm

Will be translating and posting to our sites in Spanish.