Source: iranwire.com

Kian Sabeti

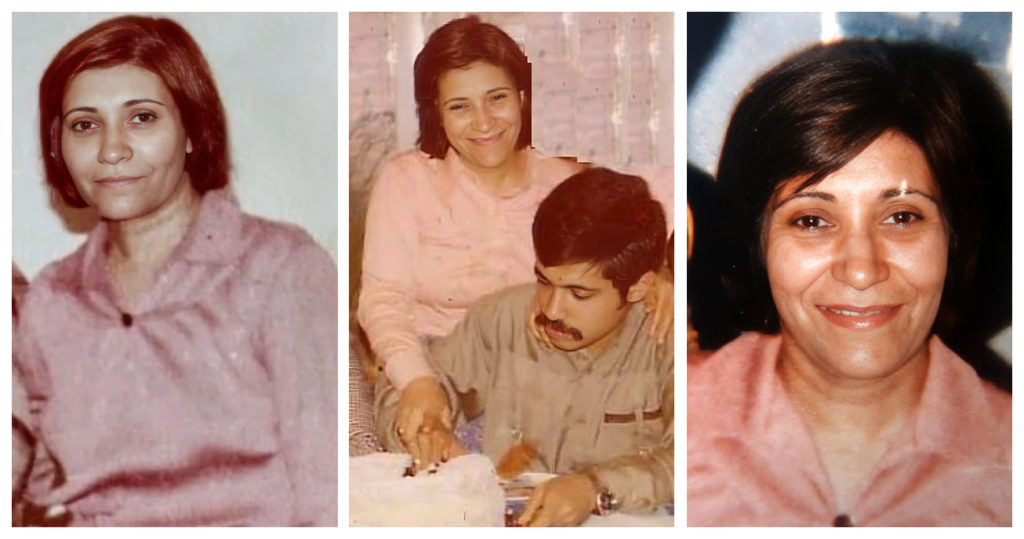

In the face of unimaginable tragedy, Nusrat Ghofrani Yaldaei, a Baha’i woman from Shiraz, demonstrated unwavering strength and faith. Her story is one of love, persecution, and sacrifice, highlighting the courage and resilience of those who faced persecution for their religious beliefs.

“I made the difficult decision not to inform Nusrat about the execution of our son, Bahram. It had happened two days prior. Whenever Nusrat would meet me, her first question would always be about Bahram’s well-being. I would assure her that everything was fine, concealing the devastating truth. As we bid each other farewell, she whispered to me that they would come for her sooner or later. On that fateful day, following our meeting, Nusrat jan and nine other Baha’i women were separated from the other prisoners and taken to Chowgan field. It was there that Nusrat met her untimely end, just two days after our beloved son’s execution. I often wonder if Nusrat had learned of Bahram’s fate in the remaining moments of her life. Perhaps one of the other women had shared the news along the way.”

These were the words of Ahmed Yaldai, reflecting on the loss of his wife, Nusrat Ghofrani Yaldaei, who was executed on June 18, 1983, along with nine other Baha’i women in Shiraz for their Baha’i faith.

Just two days earlier, on June 16, Bahram Yaldaei, their son, along with five other Baha’is, was also executed in Shiraz and for the same reason.

Who was Nusrat Ghofrani Yaldaei?

Nusrat Ghofrani, born in March 1937 in the village of Neyriz, Fars, came from humble origins. Her father, a farmer, passed away due to influenza when Nusrat was less than a year old. At the age of five, Nusrat relocated with her family to Shiraz, where she began her elementary school education.

Demonstrating a sharp intellect, Nusrat possessed an exceptional aptitude for learning and a remarkable memory. Even in her early years, she had memorised numerous religious poems and prayers, reciting them on various occasions.

Nusrat’s passion for reading extended to religious texts, prompting her to learn Arabic language and literature. Such was her mastery of Arabic that she began instructing young Baha’is in the language.

Encounter with the Hojjatieh Association

Nusrat became a prominent figure among the Bahai’s in Shiraz, and as a result endured constant harassment at the hands of the Hojjatieh Association, an anti-Baha’i group. Their harassment was relentless; whenever she ventured into the streets, Hojjatieh members would follow her, hurling insults. On one occasion, as she exited a Baha’i gathering, her bag was snatched.

One of the tactics employed by the Hojjatieh involved feigning interest in the Baha’i Faith. They would approach a Baha’i individual, pretending to seek knowledge about the religion. This person would then invite Yaldaei to provide answers to the curious seeker’s questions. However, upon Nusrat’s arrival, the supposed seeker’s companions would join in, initiating heated arguments with her. These confrontations would often last for hours until eventually, exhausted and drained, they would concede defeat and depart.

The Hojjatieh were trained in the art of sophistry, prolonging debates to wear down and vex the Baha’is. If a Baha’i sought to leave the discussion, they would accuse them of cowardice, insinuating that they lacked the fortitude to counter their arguments.

Nusrat’s daughter, Bahar, recalls the countless instances when her mother returned home, visibly worn out from these encounters, the weight of their lengthy debates weighing heavily upon her.

The Yaldaei Family During the Early Islamic Republic

Bahar fondly remembers their family’s humble circumstances, emphasizing that despite their limited means, their home was always open to those in need.

Whenever someone sought assistance or guidance, they would turn to her mother. Nusrat, a dedicated homemaker, greeted everyone with warmth and kindness and her friendly demeanor put visitors at ease.

From early morning until late evening, their house buzzed with activity, hosting a continuous stream of guests. Bahar remembers that her mother rarely set the dinner table that did not include a guest.

During those years, the Yaldaei home also became a haven for Baha’is who had lost their own homes.

Families devastated by the war with Iraq, Baha’i villagers forcibly expelled from their communities and forced to seek refuge in mountains and deserts, as well as the Baha’is of Sa’adiyeh in Shiraz, whose houses had been set ablaze by religious extremists in late 1979, all found solace and shelter under the roof of the Yaldaei family.

The Arrest of Nosrat Yaldaei – and her Son

On October 23, 1982, the Revolutionary Guards raided the homes of numerous Baha’is in Shiraz, resulting in the arrest of 38 individuals. Among those detained were Nusrat Yaldaei, her husband Ahmed Yaldaei, their son Bahram Yaldaei, and a 60-year-old woman named Iran Avargan, who lived in the Yaldaei household.

During the arrest, agents displayed a disrespectful attitude, callously tossing the Yaldaei family’s religious books into sacks and damaging picture frames that showed religious symbols.

Ahmad Yaldaei recounts the events surrounding their arrest in his book, Talaei Manzil Maqsood.

He writes, “The doorbell rang at 9pm, and I saw several guards at the entrance. They immediately commenced a thorough search of the house, rummaging through books and personal belongings. My elderly mother, who resided in the house, moved anxiously from one side of the room to the other.

“One of the agents inquired if she, too, was a Baha’i. Nusrat responded affirmatively, saying that her parent was a martyr. Upon hearing this, the guard became agitated, mockingly questioning the concept of martyrdom among the Baha’is and jesting about who would welcome their martyrs in the afterlife.

“Meanwhile, other guards who had gone downstairs returned and demanded to know the whereabouts of the basement, insisting on finding a supposed printing press. Nusrat advised them to search the rooftop, suggesting that the basement might be located there. Their frustration grew, and we explained that if there were an underground facility, they would have already discovered it.

“They then asked about our car, apparently under the assumption that we owned one. Bahram pointed to his bicycle, parked in the corner of the corridor, and sarcastically replied that the car was in the hallway. At least two vans were used to transport books and writings from our home. Subsequently, they arrested me, Nusrat, Bahram, and Mrs Avargan.”

Following the arrests, the guards left the 10-year-old son and the 90-year-old grandmother at home, instructing them not to make any attempts at contact before departing.

Execution of Bahram Yaldaei and five others

Bahram Yaldaei, born in 1955 in Shiraz, embarking on a journey that intertwined his pursuit of education and his unwavering spirit. In his hometown, he completed his primary and secondary education before studying economics at Shiraz University. Bahram earned his bachelor’s degree in 1979 and later worked as an assistant professor at the same institution.

Bahram later set his sights on earning a master’s degree. However, fate dealt him a harsh blow when he faced expulsion from university during the course of his studies. Undeterred by this setback, Bahram turned to various occupations to sustain himself, resorting to setting up a humble street stall where he sold children’s clothes.

His life took a tragic turn on October 23, 1982 when, alongside his parents, he was arrested. The subsequent eight months tested their strength and resilience as they endured the hardships of prison life.

Then, on June 16, 1983, Bahram Yaldeaie and five other Baha’is were executed, their lives cut short on the grounds of Chowgan Square in Shiraz.

Shiraz Detention Center

After their arrest, the Baha’i women were transferred to the general ward of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corp (IRGC) detention center, while Nusrat Yaldaei and one another Baha’i woman were taken to solitary confinement.

Nusrat Yaldaei endured severe pressure and torture while in the custody of the IRGC. Despite her frail and slender physique, she was subjected to punishment on multiple occasions. The interrogators continued their torment by lashing the soles of her feet, even after her back had been injured and swollen from floggings.

Following a period of solitary confinement, Nusrat’s deteriorating condition prompted a transfer from solitary to the public ward. However, neither she nor the other prisoners were allowed to speak or communicate with one another.

In a state of physical distress resulting from torture, insults, and illness, this 45-year-old mother lay in a corner of the cell, deprived of any help. After a few days, Nusrat was returned to solitary confinement. Eventually, after approximately 40 days, she was transferred to Adel Abad prison along with other Baha’is.

According to Bahar Yaldaei, her mother suffered from a stomach ulcer and required medication. However, the prison authorities refused to allow Nusrat to have her medicine, claiming that they had their own doctors and pharmacy.

Bahar recalls that her mother’s stomach pain worsened when she consumed regular bread, so she resorted to eating dry bread. But a prison official blocked her from receiving even that.

There was a time when the Baha’i women had a chance to meet with their families at the IRGC prison.

Yaldaei’s sister described the visit as follows: “When the families entered the meeting room, they saw the imprisoned women standing in a line against the wall. A glass partition separated them from the visitors on the other side.

“Families were only allowed to gaze at their loved ones. No speaking or gestures were permitted, not even a smile or a wink. The authorities ensured that we merely looked at each other without making any additional movements. After a minute or two, we were informed that the visitation was over, and the prisoners were escorted out of the room.”

Her sister recalls another occasion when they visited all the imprisoned women except for Nusrat: “We were all concerned and presumed that she had been subjected to torture, and they didn’t want us to see her in that state. We remained seated outside the prison, refusing to leave until they allowed us to see her.

“We sat for several hours, and as darkness fell, a guard approached and instructed us to enter the meeting room. We sat behind the glass, and they brought Nusrat in. She appeared very pale and unwell. We asked her how many times she had been whipped, but she simply hissed and did not respond.”

Adel Abad Prison in Shiraz

On November 29, a total of 40 Baha’is were arrested in Shiraz. As the newly arrested individuals were transferred to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps detention center, the previous detainees were taken to Adel Abad prison. After enduring 38 days of solitary confinement, Nusrat was moved to the general ward of Adel Abad prison along with other Baha’i women.

One of the Baha’i women who was imprisoned during that period wrote: “It appeared that an order had been issued to influence the prisoners at Adel Abad. The guards’ sisters inside the prison, and sometimes the guards’ brothers in the security area or during prison visits … were making efforts to guide and convert us, particularly targeting the young individuals. They saw the Baha’is as a reward for themselves. To achieve this, they would occasionally call upon a Baha’i and engage in discussions with them, whether in the common areas or the women’s quarters …”

There is no available information or documented evidence regarding the investigation and trial of Nusrat Ghofrani Yaldaei. Her right to access legal representation was denied.

In the book Flowers of Shiraz, one of the imprisoned women describes the court hearings for the Baha’i women as follows: “The court hearings lasted only a few minutes. Hojjat al-Islam Ghazaei, the Sharia judge of Shiraz, resorted to nothing but obscenities, insults, and disrespect.

“Consequently, the women had collectively decided that they would provide brief answers and refrain from arguing with him, regardless of the questions asked. Towards the end, the Sharia judge addressed a Baha’i woman and pronounced her sentence as death, presenting her with a choice between execution or conversion to Islam. The Baha’i replied, ‘I accept Islam, but I am a Baha’i.’ This response further enraged the ruler, and he shouted loudly, ‘Get lost, get out! Let Islam devour your head! Your sentence is death!'”

Sentencing, Pressure to Recant and Execution

On February 1, 1983, the Shiraz Revolutionary Court published announced in a publication called Khabar Jonob the death sentence of 22 Baha’is from Shiraz.

Following this news, on February 22 of the same year, the Khabar Jonob newspaper featured an interview with the judge, the Sharia judge, and the head of the Shiraz Revolutionary Court, under the threatening title “I Warn the Baha’is to Embrace Islam.”

The day after the interview was published, Siddiya Miremadi, the revolutionary prosecutor of Shiraz, gathered the detained Baha’is in a hall and informed them that this meeting marked the end of the evidence stage and that all except a few individuals had been sentenced to death.

He stated that these rulings had been approved by the Supreme Judicial Council, although he had not yet signed them. He offered the Baha’is a choice: conversion to Islam would grant them freedom, while refusal to convert would result in the execution of the sentence.

At the end of the meeting, the prosecutor allowed each of the prisoners, both male and female, to visit their immediate family members who were also imprisoned. After four months apart, mothers and sons embraced each other.

The boo, Talaei Manzil Maqsood, describes this meeting: “Today, at the conclusion of the meeting, when the prison permitted male and female relatives to meet, Bahram and his mother embraced.

“Until the last moment, they held onto each other tightly and talked. It seemed as though the mother and son realized this meeting might be their last in this world. Perhaps the mother, who had always taught her son endurance and bravery, inspired his courage, or perhaps Bahram admired his mother’s strength and bravery.”

In the book Jonoud Malkut, which details the biographies of some of the executed Baha’is in Shiraz, Nusrat Yaldai is quoted as saying, “Bahram told me, ‘Mom don’t be afraid, be resilient, even if they cut me to pieces in front of you.'” In response, she reassured him, saying, “Rest assured, my son. If they execute me too, don’t be saddened.”

And from mid-June of 1983, as ordered by the Shiraz Revolutionary Prosecutor Mir Emadi, hearings were conducted for the imprisoned Baha’is.

In these meetings, each Baha’i was given four opportunities to convert to Islam and save their lives. If they did not recant, the prosecutor claimed that “God’s decree” would be executed upon them.

Following the prosecutor’s order, nine Baha’i women were taken to be urged to repent four times, yet none of them renounced their faith.

Nusrat Yaldaei, however, was the only Baha’i prisoner who was not taken to these hearings, even by Mir Emadi’s command. It remains unclear whether the steadfastness of the nine women during the convert meetings rendered it futile to bring Nusrat to such sessions, or if her courage and responses during the interrogation period dissuaded them from doing so.

After meeting with their families, these 10 Baha’i women were abruptly removed from the ranks of the prisoners and taken to Chowgan Square in Shiraz for execution. They were hanged one by one in order of age, with each forced to witness the death of the woman preceding her.

At the time of her execution, Nusrat Yaldaei was 46 years old. She was not permitted to write a will, and the bodies of these ten women were buried by the officers in the Baha’i cemetery of Shiraz without any religious ceremonies being performed.

Leave a Reply