Source: iranwire.com

Kian Sabeti

“Granny arranged bail for her granddaughter with difficulty, but she was happy that Shirin would be released in an hour. Rouhi, Shirin’s close friend, had been released on bail the day before, but she could not arrange bail for Shirin and posting bail was delayed by a day. When she went to post bail, the person responsible for registering it told her that no Baha’i could be released on bail. ‘But yesterday a few were released on bail and my granddaughter is one of them,’ said Granny. The guy said that those released on bail must return as well! The grandmother said nothing at all. Earlier she had been thinking about the food that Shirin likes so she could cook it for her that night.”

The “Granny” was the grandmother of Shirin Dalvand, a 26-year-old woman and a native of Shiraz, who was executed on June 18, 1983, along with nine other Baha’i women, because of their faith.

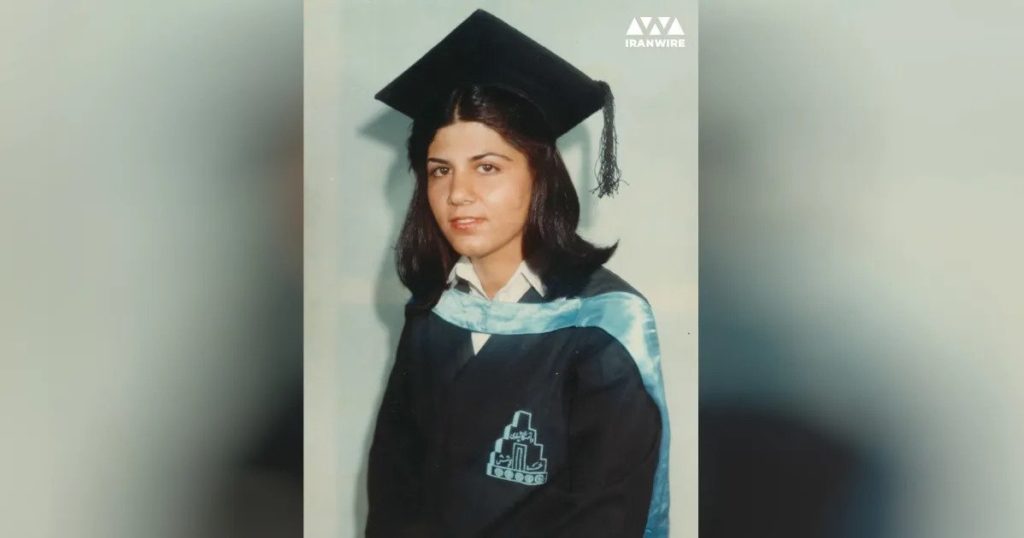

Shirin Dalvand, whose given first name was Shahin, was born in Shiraz to a Baha’i family on January 4, 1957. A part of her childhood was spent in Mashhad and the rest in Shiraz. Shahin’s family affectionately called her “Shirin”, Persian for “Sweet,” when she was a child, and her friends and acquaintances called her by the same name. Shirin finished primary school and high school in Shiraz and, after receiving her high school diploma, continued her education at Pahlavi University in Shiraz in sociology.

Her university career was interrupted with the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the shutdown of universities across Iran. Shirin and her family emigrated to Britain but, after the universities were reopened, she and her father returned to Iran. Shirin resumed her studies in Shiraz and graduated with high grades. Her dissertation, “A study of the characteristics of a group of drug addicts and the reasons for their addiction,” caught the attention of her professors who invited her to participate in a TV program on the subject, although this did not happen because she was a Baha’i.

Shirin’s father returned to the UK. He asked Shirin go with him, now that she had graduated, but she told him during a telephone call that she wanted to remain in Iran despite all the problems that the Baha’is were facing after the Revolution.

Executions, arrests, confiscation of properties, destruction of Baha’i cemeteries, expulsion from government jobs, expulsion from education or academic roles, hate speech against Baha’i beliefs and desecration of Baha’i religious sites had all arrived with the establishment of the Islamic Republic. Iran’s new government knew that the home of Bab, the founder of the Babi faith and forerunner of the Baha’i faith, was in in Shiraz and that it was a sacred place for Baha’is in Iran and around the world. The authorities believed that if they confiscated and destroyed this home, they could hasten the disintegration of Iran’s Baha’i community.

The harassment of the Baha’is in Shiraz had, in fact, already begun a few weeks before the culmination of the Islamic Revolution with the torching and destruction of 165 Baha’i homes.

Shirin saw these events with her own eyes but, despite the dangers threatening the community, she wanted to stay in her birthplace or, as she put it, to stay and serve Iran. She lived at her grandparents’ home from the time that her father left until she was arrested.

Shirin managed her father’s business affairs in Shiraz in his absence. She also dedicated time to visiting and comforting the families of Baha’is who been imprisoned or executed. And she tried, as much as she could, to help Baha’i villagers who had been driven out of their homes.

Shirin’s Arrest

On the evening of November 29, 1982, Shahin and her close friend Rouhieh (Rouhi) Jahanpour went to Rouhi’s home after visiting with another Baha’I, Ms. Gohar-Riz, whose husband was in prison. The Revolutionary Guards had arrested 40 Baha’is in Shiraz in that month alone and Ms. Gohar-Riz’s husband was one of them.

On their way to Rouhi’s home, the two noticed that a man was following them. When they reached the Jahanpour home, Shirin called her grandmother and told her that she would spend the night there. Then, at about 11pm, Revolutionary Guards agents banged on the door and, after the door was opened, seven or eight of them pushed their way in. Without producing any warrants, they searched the home, confiscated religious books and pictures and, in the end, arrested Shirin and Rouhi.

The agents used offensive language and called the residents “unclean”. Rouhieh Jahanpour says that when they were arrested the agents told them: “We have no doubt that we are doing the right thing because we are preparing the way for the return of Holy Mahdi [the 12th Shia Imam]. We must get rid of all of you because the only reason that he has not returned is the existence of you, the unclean.”

On that night, 40 Baha’is in Shiraz were arrested at their homes by the Revolutionary Guards. The agents went to the home of Shirin’s grandmother as well and left after searching the residence and confiscating Baha’i books and pictures.

Shirin’s Interrogation

The arrested Baha’is were taken to the detention center of the Revolutionary Guards in Shiraz, where they were interrogated, harassed, threatened and mistreated in other ways. The interrogators had two goals: forcing the Baha’is to recant their faith and extracting the names of other Baha’is. In her memoirs Olya’s Story, Olya Roohizadegan, another of the detainees, writes that after a couple of days they took her and other women out of their cells, blindfolded them, and stood them against a wall for hours as they showered them with insults. “Are you still Baha’is?” the agents screamed at them, and when all of them, without exception, answered that they were, the Guards shouted “Kill these heathens! Fire!”

Shirin was a calm, polite and shy young woman, according to those who remember her, and she had never claimed to be brave or strong. But she he resisted the threats and violence of the interrogators who wanted her to renounce her faith and convert to Islam. When the interrogators failed to force the detainees to recant their Baha’I faith, the interrogations turned into debates, in which one side would use violence to prove its points.

Adel Abad Prison and the “Project to Repent”

Around the end of December, the Baha’i detainees were transferred to Adel Abad Prison in Shiraz, where there was a ward for women. By order of the prison warden, each floor of this ward held a specific group of inmates. One floor was for the “repentant”, those who had renounced their religious or political beliefs. The next floor was for “waverers” and the third floor was for inmates who were called the “villains”. Baha’is were kept among the “villains”. On this floor were around 70 to 80 women who had been imprisoned on various charges. By order of Zia Mir-Emadi, the revolutionary prosecutor, only the “repentant” inmates were allowed to receive visitors and take leaves of absence or be eligible for parole.

The questioning of Baha’is by an examining magistrate started after they were transferred to Adel Abad Prison. The sessions were part of a project to convince the Baha’is to “repent” – an effort that had begun in the Revolutionary Guards detention center. The magistrate threatened Baha’i inmates that they must expect they death penalty if they refuse to convert to Islam. Prison guards also participated in this project. They repeatedly went to the cells of Baha’is, summoned prisoners, or spoke to them in the prison yard in an attempt to “guide” them to repent. The Baha’is, like other inmates, were also required to visit the prison library to study Islamic books and treatises.

Shirin’s Bail Denied

After the examining magistrate had finished interrogating Baha’i prisoners, bail was set for several of them. Shirin’s property bond was set at 500,000 tomans. Her grandmother was unable to post the bail on the same day; but the next day, when she went to court to post it, she was told that the bail had been canceled and her granddaughter must remain in prison.

By the order of Majid Torabpour, Adel Abad’s warden, only immediate relatives could visit prisoners and, as a result, Shirin was the only Baha’i inmate who received no visitor for a long time. On the days when prisoners had visitors, she was alone in her cell until her cellmates returned from meeting their families. Shirin’s grandmother continuously brought food and clothing, but she was not allowed to meet her granddaughter. Shirin always spoke about her grandmother, while in prison, and eagerly awaited the day when she would be allowed to see her. One day, at least, after the other visitors were gone, she was summoned and finally met her grandmother after several months. That day may have been Shirin’s sweetest moment while in prison.

The Kangaroo Court

As with other Baha’is, the trial of Shirin Dalvand lasted only a few minutes, behind closed doors, and she was not allowed to have a lawyer. Hojatoleslam Ghazaei, the Sharia judge of Shiraz and the head of the Shiraz Revolutionary Court, would announce at the end of each trial of a Baha’i: “Islam or death!”

A cellmate of Shirin was able to capture the conversation between her and the judge.

“Was she going to remain faithful to her faith until the moment of execution” the judge asked.

“I hope that, with the grace of God, I will stay resolute in my faith until the last moment of my life,” Shirin replied bravely.

“You dying has nothing to do with the grace of God. You want to be executed,” said the judge in anger.

“Your honor, we Baha’is believe that even a leaf does not fall off the tree unless it is God’s will. My will or your will does not make a difference. God’s will is always the only factor,” replied Shirin.

The Day 22 Baha’is Were Sentenced to Death

On February 12, 1983, a local newspaper, Khabar-e Jonoub, reported that 22 Baha’is had been sentenced to death. On February 22, in an interview with the same newspaper, Hojatoleslam Ghazaei confirmed the report and threatened the Baha’is that if they did not embrace Islam, soon enough the nation of Islam would do its Sharia duty and the Baha’is must know that they would be “uprooted”.

These statements by Hojatoleslam Ghazaei contradict repeated claims by the Islamic Republic officials that Baha’is are not arrested and executed because of their religious beliefs.

When news of the death sentences reached inside the prison, nobody imagined that Shirin would be among them. The inmates themselves had made lists of those whom they believed could be put to death. Shirin’s name was on none of these lists.

Zia Mir-Emadi, Revolutionary Prosecutor of Fars Province, made a final attempt to coerce the Baha’is into recanting their beliefs, by announcing that he would give the Baha’is who had been sentenced to death four chances and, if they did not, they would be hanged. But he got nowhere with it and none of them, including Shirin, renounced their beliefs or converted to Islam. “I accept Islam, but I am a Baha’i,” they wrote, when they were asked for their decisions.

On March 17, 1983, six of the Baha’is from the men’s ward were executed. And at 5pm on Saturday, June 18, 10 Baha’i women met with their families without knowing that it would be for the last time. During this meeting that they learned of the execution of the six Baha’i men. As the prisoners were returning to their cells, Majid Torabpour, Adel Abad’s warden, separated Shirin and nine other women and sent them to a room.

One of Shirin’s cellmates describes what took place: “I was standing next to Torabpour. He had a list in his hand and, on that list, the names of the men who had been executed were crossed off. Mr. Torabpour called the name of each woman, each of whom answered with a smile. He ordered them to a room across from where we were. I followed each one of them with my own eyes from the paper to that room. When the list was finished, some of us remained, and Mr. Torabpour ordered one of the guards to return us to the ward. I looked to that room for a last time. I saw only Shirin, leaning against a table, speaking with the others. When she noticed me, I bid her farewell with my head and she waved her hand at me.”

Shahin (Shirin) Dalvand was 26 years old when she was hanged. The Revolutionary Guards buried her and the other nine women, without informing their families, and without religious rites. One eyewitness later told the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center that these 10 Baha’i women were hanged one by one.

Leave a Reply