Source: iranwire.com

Kian Sabeti

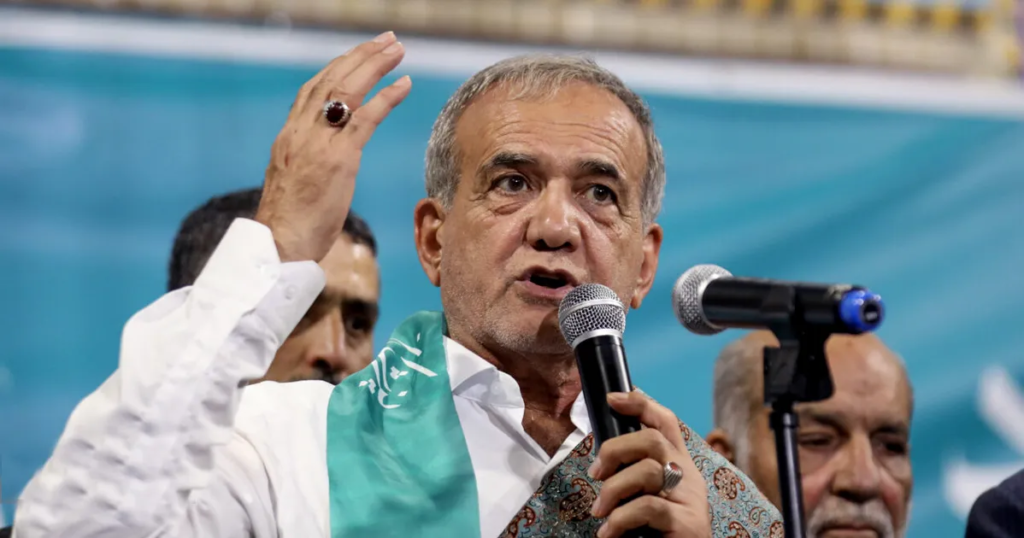

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian’s calls for national unity and equal rights at the UN General Assembly stand at odds with the ongoing systematic persecution of religious minorities in Iran.

During his election campaign and subsequent visit to New York, Pezeshkian emphasized a vision of an inclusive Iran.

“Iran belongs to all Iranians,” the president declared at the UN, saying he came to address “the values and beliefs that the UN claims to stand for” and challenged the international body to “demonstrate your commitment in action, not just in words.”

However, these statements contrast with the documented treatment of Iran’s Baha’i community, the country’s largest religious minority.

A recent Human Rights Watch report, “The Boot on My Neck,” describes the Iranian government’s 45-year persecution of Baha’is as a crime against humanity under international law.

The systematic oppression of the Baha’i community has persisted for more than four decades, raising questions about the sincerity of the administration’s proclaimed commitment to protecting the rights of all citizens, regardless of “race, ethnicity, religion, or belief.”

Arrests and Heavy Sentences

Arrests and court sentences for Baha’is began immediately after the 1979 Islamic Revolution and continue to this day. Although the execution of Baha’is was common in the first two decades of the Islamic Republic, international pressure eventually led to the removal of capital punishment for Baha’is.

However, they continue to face imprisonment.

Following the 2022 protests, arrests of Baha’i citizens, especially women, escalated, and many were sentenced to prison. Despite Pezeshkian’s promises, no improvements have been seen in the treatment of Baha’is, and prison sentences for them on ideological charges continue, with even harsher rulings issued by the Revolutionary Courts.

In recent months, dozens of Baha’is have been sentenced to prison in cities such as Tehran, Isfahan, Shiraz, Kerman, Yazd, Karaj, Rasht, and Babol.

Notably, ten Baha’i women were collectively sentenced to 90 years in prison and fined for “deviant and anti-Islamic educational activities” due to organizing English, painting, music, and yoga classes, as well as nature camps for Iranian and Afghan children.

In another case, Baha’i musician Behrad Azargan was sentenced to 11 years in Tehran on charges of “propaganda against the Islamic Republic” through music classes.

Niyousha Sabet and Sousan Eid Mohammadzadegan, two other recent Baha’i convicts, were sentenced by a Revolutionary Court in Babol to five years in prison and banned from all educational activities for 18 months, accused of “spreading the Baha’i faith through psychology workshops and classes.”

Another case involves Payam Vali, a Baha’i who is serving the third year of a six-year sentence in Karaj prison. He received an additional eight months in prison after being accused of spreading information about his mistreatment during interrogations.

Faraz Razavian was sentenced to two years and one day without interrogation, following a court hearing for his mother, Mozhgan Samimi, who was also sentenced on similar charges in Rasht.

Continued Arbitrary Detentions

The past 100 days have seen a continuation of arbitrary detentions of Baha’i citizens. The detainees often lack access to legal counsel, are held without disclosure of charges or detention locations, and are prohibited from making contact with family members.

On September 18, Negar Misaghian, the mother of a two-year-old, was detained in Shiraz in front of her child. Her husband, Mahboob Habibi, was subsequently arrested on September 28 and transferred to the Shiraz intelligence detention center.

In Tabriz, several Baha’i homes were raided on September 26, resulting in the arrests of Iraj Nourasteh, Sina Aghdasi, and Azam Azmoudeh. Azmoudeh was arrested in front of her distressed four-year-old child.

These cases represent only a fraction of the Baha’i citizens arrested since Pezeshkian’s presidency began. Additional detentions have been reported in cities including Birjand, Kerman, Tehran, and Karaj.

Denial of Higher Education

For over four decades, Baha’i citizens in Iran have been denied access to higher education. In recent years, a handful of Baha’is have managed to enrol in universities, only to be expelled once their Baha’i faith was confirmed.

The denial of education is based on a directive from Iran’s Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution issued in 1990.

The order stated, “In universities, both at the time of admission and during their studies, if it is confirmed that individuals are Baha’i, they shall be denied entry to the university.”

During his election campaign, President Pezeshkian promised that students would not be expelled for their beliefs and that the rights of religious and ethnic minorities would be respected. However, despite these assurances, the exclusion of Baha’is from universities has continued under his administration.

Negar Zargani, a student at Isfahan University, was summoned by the university’s security office on August 5 and questioned about her activities and connections to the Baha’i community.

She was asked to sign forms denying any adherence to Baha’i institutions and confirming that she had no association with the Baha’i faith. When she refused, she was barred from entering the university.

A similar experience happened to Pariya Vafaei, a Baha’i student at Tehran University. She also refused to sign such forms and was subsequently denied entry to the university.

Yavar Shams was blocked from entering Isfahan University. He was summoned by the university’s security office, where he was interrogated by an officer who asked questions unrelated to university admission or exams but focused on his family, the Baha’i community, and their activities.

Destruction of Baha’i Cemeteries

The destruction of Baha’i graves has been an ongoing policy since the early days of the Islamic Republic. Hundreds of Baha’i cemeteries across Iran have been seized and destroyed, with graves leveled and bodies exhumed.

For years, Baha’i families had no place to bury their dead, until the government allocated barren, rocky lands in remote areas such as Baha’i cemeteries in various cities.

These cemeteries have become targets for repeated attacks by seemingly unknown assailants. It appears that Baha’i citizens in Iran are not safe from persecution even after death.

On August 6, the old Baha’i cemetery in Ahvaz was set on fire in an act of brutal and inhumane religious harassment. It drew significant media and human rights attention, yet no response or investigation was initiated by Pezeshkian’s administration.

Under Pezeshkian’s presidency, there have also been numerous cases of Baha’is being fired from their jobs, businesses being forcibly closed, homes being searched, and people being summoned for questioning, among other forms of rights violations.

Pezeshkian’s record shows no positive steps have been taken to ease the pressure on the Baha’i community – in some cases, the harassment and oppression have even intensified.

Leave a Reply