Source: www.theguardian.com

Friday 4 March 2016 02.00 EST

After the success of moderates in the polls, hopes grow that Rouhani will follow his nuclear deal efforts by tackling issues including the high number of executions and arbitrary detention

Boosted by the victory of his moderate allies in recent elections in Iran, the all-smiles President Hassan Rouhani is now in a stronger position to pursue the much-neglected human rights challenges facing his country.

Although rights violations in Iran are largely carried out by a judiciary and parallel intelligence apparatus that act independently of Rouhani’s government, the president, as the most senior elected official in the Islamic republic, is responsible under the constitution to protect his citizens.

In the first two years of his presidency, Rouhani’s focus was on resolving the nuclear impasse, which appeared to be as much a priority for his administration as it was for the electorate. With the nuclear dossier now almost closed and his main campaign promise delivered, Rouhani is being urged to shift his attention towards human rights, which critics say he has put on the backburner. His promise of establishing a citizens’ rights charter is yet to materialise.

Nasrin Sotoudeh, a human rights lawyer living in Iran, said on Wednesday that she was pleased with the election results, even though a significant number of candidates had been disqualified from standing.

Sotoudeh said human rights violations remain a big concern for Iranian society but added it was important people managed their expectations, to avoid disappointment.

“We do not expect the president to play the role of the opposition,” she said, adding that she did not want Rouhani to push beyond his capacity but to manage institutions not yet under his influence, such as the intelligence ministry.

“We believe Iranians themselves would also need to make an effort to improve their rights situation but the president can also pursue policies that will have positive consequences on human rights.”

How much Rouhani delivers on greater domestic freedom in his remaining two years as president is likely to affect his chances of seeking re-election next year.

Alarming rate of executions, including juveniles

Former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was once single-handedly the most significant factor in damaging Iran’s global image with his inflammatory statements denying the Holocaust. But that has now given way to the alarminglyhigh level of capital punishment.

News of positive developments in Iran is punctuated every so often by the execution of a new group of people. Mohammad-Javad Larijani, the head of Iran’s state-run high council for human rights, has indicated that there are efforts to take a new law to parliament that will result in “almost 80% of the executions” going away but it is unclear if that effort is serious.

Most people executed are sentenced to death for drug offences, with trials widely condemned as unfair. Sotoudeh said too many cases have only one judge presiding from the beginning to the end when a death sentence is issued without judgments being challenged or thoroughly examined. It emerged last month that the entire adult male population of a village in southern Iran had been executed for drug offences, said the vice-president for women and family affairs.

According to Amnesty International, Iran remains a prolific executioner, second only to China. In 2014, at least 753 people were hanged, of whom more than half were drug offenders. In 2015, the group said it had recorded “a staggering execution rate” in the country, “with nearly 700 people put to death in the first half of the year alone”. It said in a report published in January that 73 juvenile offenders had been executed between 2005 and 2015. One, Amir Amrollahi, is currently on death row even though he committed the crime when he was 16.

Not everyone on death row in Iran is a drug smuggler. Mohammad Ali Taheri, who has been held in solitary confinement since May 2011, is facing death for “spreading corruption on earth” through establishing a spiritual group calledErfan-e Halgheh and promoting beliefs and practices that authorities deem un-Islamic.

Opposition leaders under house arrest for five years

Iran’s three main opposition leaders, Mir Hossein Mousavi, his wife Zahra Rahnavard, and Mehdi Karroubi, have been confined within their houses since their movements were restricted in February 2011 without trial.

Mousavi and Rahnavard are in their house in a dead-end alley in Tehran calledAkhtar, under constant heavy guard by the police. Karroubi is under similar circumstances in another part of the capital. They have largely been kept incommunicado although have recently been allowed regular visits by some immediate family members. There are serious concerns about their health, withan image emerging online of Mousavi in May 2014 showing him in a Tehran hospital bed due to a heart condition. Former president Mohammad Khatami, the leader of the reformist movement, is not under house arrest but is facing restrictions on his movement and activities. Iranian media is banned from publishing his name or photograph.

Prisoners of conscience languishing in jail

The exact number of prisoners held in Iranian jails on political grounds or because of their beliefs and civil activities is unclear. A number of them, including bloggerHossein Ronaghi Maleki, have serious health issues and need medical care. Amnesty said he “has only one functioning kidney and, according to his doctors, needs constant monitoring and access to specialised medical care, which he cannot get in prison”. He was taken back to Tehran’s notorious Evin prison in January to resume his 13-year sentence, which he received after the authoritiesdeemed his blog insulting to the supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

There are at least 18 female prisoners of conscience, including Narges Mohammadi, a journalist and and spokesperson for the Centre for Human Rights Defenders. Mohammadi, a mother of two and winner of the 2009 Alexander Langer award for her human rights activities, has developed an undiagnosed epilepsy-like disease while in prison which causes her to temporarily lose control over her muscles. Other prisoners include student activist Bahareh Hedayat, artist Atena Farghadani – sentenced to 12 years – and anti-death penalty activist Atena Daemi – sentenced to 14 years. Minoo Mortazi Langeroudi, a women’s rights activist and member of the Council of Melli Mazhabi Activists, was sentenced to six years in June 2015.

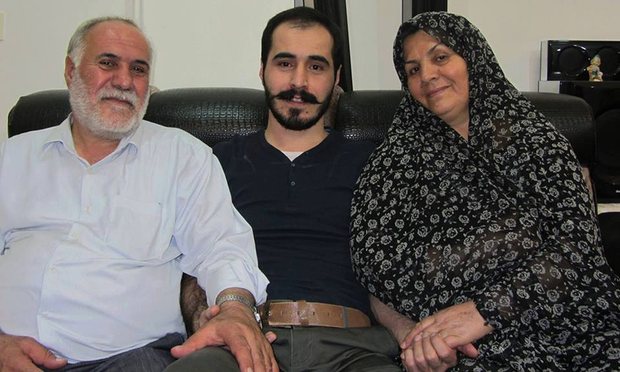

Other people are persecuted outside prison, with Amnesty saying earlier this week that filmmaker Hossein Rajabian, his brother Mehdi Rajabian and Yousef Emadi, both musicians, risk imminent arrest after an appeal court upheld their prison sentences on charges relating to their work. “These sentences lay bare the absurdity of Iran’s criminal justice system, which brands individuals as criminals merely for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression through making music and films. These young men should never have been arrested, let alone brought to trial,” said Said Boumedouha, Amnesty International’s Middle East and North Africa deputy director.

Civil society is still active although many freedoms are suppressed and basic rights denied. For example, women are obliged to wear hijab and are not allowed to watch matches in stadiums alongside men. In March 2015, Qasem Exirifard, a physics professor, lost his job because he was told he had a feminine voice that prevented him from effectively communicating with his students. Exirifard said on Thursday that he was beginning a hunger strike after failing to overturn the university’s decision.

Judiciary heavily influenced by intelligence apparatus

One of the biggest challenges is the judiciary. The head of the judicial system is appointed by the supreme leader and no elected officials, such as the president, can hold him to account. The crackdown on journalists and political activists is spearheaded by a small group of judges believed to be heavily influenced by the intelligence apparatus at the Revolutionary Guards. Two judges, Abolghassem Salavati and Mohammad Moghiseh, are accused of repeatedly losing their judicial impartiality and overseeing miscarriages of justice in trials in which journalists, lawyers, political activists and members of ethnic and religious minorities have been condemned to lengthy prison terms, lashes and execution. Common violations include holding trials behind closed doors which last only a few minutes and lack essential legal procedures, intimidating defendants, breaching judicial independence by acting as prosecutors themselves and depriving prisoners of access to lawyers.

Businessman Siamak Namazi, an Iranian-American national, who was jailed with no explanation in October after visiting his family, has no access to lawyers. His 80-year-old father, Baquer Namazi, a former Unicef official, has also been arrested and denied access to lawyers, say the family.

Treatment of Bahá’ís and other religious and ethnic minorities

The Bahá’ís are the most persecuted religious minority in the country, with the faith’s seven leaders – Fariba Kamalabadi, Vahid Tizfahm, Jamaloddin Khanjani, Afif Naeimi, Mahvash Sabet, Behrouz Tavakkoli and Saeid Rezaie – each serving a 20-year jail term.

Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians are recognised as accepted religious minorities. They have parliamentary representatives and the captain of the national football team is a Christian but the Bahá’í faith is banned and more than 100 Bahá’ís are estimated to be in prison. Many Bahá’ís have been expelled from universities and others jailed for providing education to other Bahá’í.

Muslims whose denominations are not accepted, such as the Gonabadi dervishes also face persecution, with members often imprisoned. Gonabadi dervishes face persecution, discrimination, harassment, arbitrary arrests and attacks on their prayer houses, Amnesty said.

Rouhani has made some improvements after promising in his election campaign in 2013 to protect and promote the rights of groups such as Arabs, Azeris, Kurds, Baluchis, Turkmens and Armenians. He appointed Ali Younesi, a former intelligence minister, to serve as his special assistant in minorities’ affairs, marking the first time such a position was created. But minorities still face widespread discrimination and inequalities in areas such as access to education, welfare and having their mother tongue taught at school.

The treatment of Afghan refugees

Nearly 1 million Afghan people are registered as refugees but there are thought to be at least 2 million more who are living illegally. The majority face difficulties in continuing education, having bank accounts, receiving paperwork to leave the country or accessing work. Recognised Afghan refugees will never be able to obtain Iranian nationality regardless of how long they have spent in the country. Discrimination is rife, with many using the derogatory term “Afghani” (Afghan’s national currency), but civil rights activists have taken steps to raise awareness. It emerged last year that authorities were recruiting Afghan refugees on a daily basis to fight in Syria, promising them a monthly salary and residence permit in exchange for what it claims to be a sacred endeavour to save the holy Shia shrines in Damascus.

Intimidation of journalists and lawyers

The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists said, in a December 2015 report, that more journalists are in jail in Iran than any country other than China and Egypt. Jason Rezaian, the Washington Post reporter held for over a year, was released as part of a prisoner swap with the US in January. A number of journalists, bloggers and cartoonists are in prison and many have faced long sentences, such as Ahmad Zeidabadi, who was recently made the International Press Institute’s 68th World Press Freedom Hero.

The constitution says censorship is prohibited but the country has one of the world’s worst records for press freedom and dozens of newspapers have closed in the past decade. Many journalists, such as those working for the BBC’s Persian service, cannot return to Iran for fear of arrest. Journalists also face harassment including bars from leaving the country, passport confiscation and being summoned for interrogation.

Reporters Without Borders said: “With a total of 37 journalists and citizen-journalists currently detained, Iran is still one of the world’s five biggest prisons for media personnel and is ranked 173rd out of 180 countries in the 2015 Reporters Without Borders press freedom index.” It added that Afarine Chitsaz of the daily Iran, Ehssan Mandarinier, the editor of the daily Farhikhteghan, Saman Safarzai of the monthly Andisher Poya and Issa Saharkhiz, an independent journalist, were arrested in November. Roya Saberi Negad Nobakht, a citizen-journalist with dual Iranian and British citizenship, is serving a five-year sentence and has repeatedly fainted while in prison.

Many lawyers are also in prison, including Abdolfattah Soltani, who is serving a 13-year sentence, and Mohammad Seifzadeh, facing six years. Ahmed Shaheed, the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran, warned in his latest report that parliament was introducing a bill which “envisions significant government influence over the activities of the Iranian Bar Association” that would “bring the relatively independent association under greater supervision of government officials”.

Leave a Reply