Source: www.huffingtonpost.com by Layli Miron

I have been, most of the days of My life,

even as a slave, sitting under a sword hanging on a thread,

knowing not whether it would fall soon or late upon him.

~Bahá’u’lláh, Founder of the Bahá’í Faith, in a letter to the Persian Shah (1868)

Recently, my husband and I sat spellbound by The Prophet, a gorgeous film adaptation of the 1923 book of poems by Kahlil Gibran. In the film, the prophetic writer and artist, Almustafa (aka Mustafa), is a prisoner of an oppressive government, confined on a Mediterranean island called Orphalese. While the government is not named, various clues point to the Ottoman Empire. The only crime Almustafa has committed is using his faculty for words to advocate for the common folk—which endangers the authorities’ power.

Almustafa’s equanimity under the duress of unjust confinement reminded me of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, who led the Bahá’í Faith from 1892 to 1921. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the son of Bahá’u’lláh, spent most of his life as a prisoner of the Ottoman Empire, starting in his childhood, when in 1853 his family was banished from their homeland of Persia (Iran), until 1908 when the Young Turks revolted.

Bahá’u’lláh and his family were punished for the crime of believing God continued to speak to humanity. They were prisoners of faith—prisoners of conscience.

During his decades of confinement, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá suffered intense privations. Even after his imprisonment ended, his life was still “under a sword hanging on a thread”—for example, in 1918, Turkish commander Cemal Paşa threatened to crucify him. Nevertheless, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá remained utterly reliant on God; as he wrote,

Affliction beat upon this captive like the heavy rains of spring,

and the victories of the malevolent swept down in a relentless flood,

and still ‘Abdu’l-Bahá remained happy and serene,

and relied on the grace of the All-Merciful.

That pain, that anguish, was a paradise of all delights;

those chains were the necklace of a king on a throne in heaven.

Content with God’s will,

utterly resigned, my heart surrendered

to whatever fate had in store,

I was happy.

For a boon companion,

I had great joy.

(From Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá)

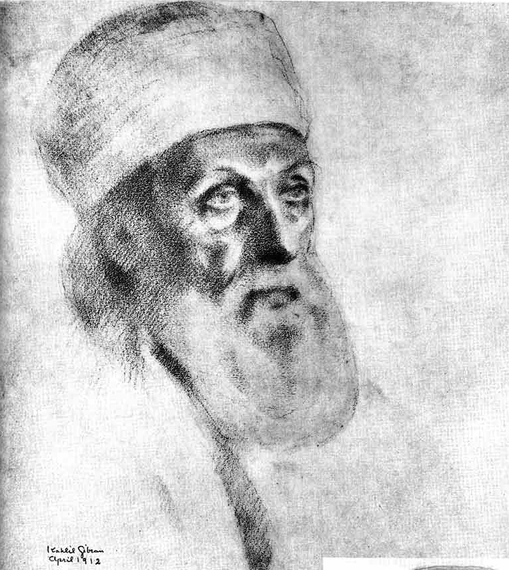

In 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá traveled to North America, where, in New York City, he met Kahlil Gibran. Some have speculated that Gibran based Almustafa on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The film’s premise of imprisonment brings this likeness to the fore.

A century after ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s 1908 release, seven Bahá’ís in Iran were arrested and jailed. That was May 14, 2008. May 14, 2016, marks eight years that they have spent imprisoned in Iran. These prisoners, called the Yarán (“friends”), are being punished for believing God continued to speak to humanity through Bahá’u’lláh.The Iranian government condemned the Yarán to spend twenty years in prison, reportedly reduced to ten. Like many other prisoners of conscience around the world, and like Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá before them, they are suffering for holding fast to noble beliefs.

My grandfather emigrated from Iran to the United States before the 1979 Revolution. As an American, I take my freedom to practice the Bahá’í Faith for granted. But if I had been born in Iran, I would not have been permitted to attend college because of my religion. If I had assumed an informal position of leadership in the Bahá’í community, as the members of the Yarán did, I might have been cast into prison.

It is hard for me to imagine spending days in captivity, let alone years, but the poems by imprisoned Yarán member Mahvash Sabet, which were published in translation in Prison Poems (2013), give a glimpse of the hardship. In “The Great Outdoors,” she reflects on prisoners’ deprivation of nature, but demonstrates her perseverance:

When you finally leave this sultry atmosphere

and arrive at last in some green pasture far outdoors—Go lose yourself under an endless waterfall,

and sit beneath the teeming and relentless rain.

Go warm yourself under the benediction of the sun

and speak with no one but the flowers of the meadow.

Let your heart brim with the lovely and the beautiful,

fill up your arteries with the rapture of the joyful,

and let love sing to your very nerve endings

till all your senses synchronize once more

with this pure scent, this peaceful fragrance

of the great outdoors.In fact, it is quite enough for me

just to look forward to that vast immensity

—of air—

even if I never reach it, never get there.

Mahvash, I am thinking of you and your fellow prisoners of conscience as I breathe the free and fragrant air of Pennsylvania springtime.

Leave a Reply