Source: iranwire.com

Waves of repression and turmoil at home has made Iran a diasporic nation. In particular, since the 1979 revolution, millions have left their homeland in search of a better future elsewhere.

One of the primary challenges of these exilic migrants has long been the recognition of their professional degrees abroad. A Persian surgeon driving a taxi in Vienna or Toronto is an oddly familiar encounter. Iranians abroad have joined others in lobbying hard for recognition of their degrees.This is why an initiative like UNESCO’s Global Convention on the Recognition of Higher Education Qualifications should naturally be welcomed by droves of Iranians. The convention has been in the works since 2016, when UNESCO’s General Conference (a meeting of all its member states) established a drafting committee. Its simple aim is to bring about a universal system of degree recognition to help more than four million students who now study outside their home country (estimated to reach eight million by 2020.) The convention will replace a plethora of regional conventions, none of which count Iran as a member (A Paris convention in 1978 brought Arab countries in line and one in Bangkok in 1983 brought in other countries of the Asia-Pacific region.)

Yet one can count on Iranian politics to make such a bland-sounding topic a subject of high controversy — and to even link it to regime hardliners’ favorite boogeymen, Israel and the Baha’is. According to Mahmood Sadeghi, a popular reformist MP from Tehran, Mohammad Mehdi Zahedi, a conservative MP from the southern city of Kerman who heads the parliamentary Education and Research Committee, has lobbied against the UNESCO convention. Zahedi is among the influential members of parliament with an illustrious past, having served as Minister of Higher Education (2004-2009) and ambassador to Malaysia (2009-2012) during the presidency of the hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

According to Sadeghi, Zahedi had two particular criticisms of the convention. The first was that Israel could also join the convention (a bizarre objection, since Iran is already party to many international treaties and organizations that count Israel as a member, inducing the United Nations itself). Secondly, if Iran joined, it would have to accept the academic qualification of Baha’is who study abroad.

This second complaint is particularly jarring. Baha’is form the largest religious minority in Iran, numbering more than 300,000 people. The Islamic Republic persecutes them as a matter of routine, and it has long adopted an official policy of barring them from higher education. Iranian Baha’is are thus not allowed to enter university, and their path for development is seriously blocked. That Zahedi would raise the barring of Baha’is from higher education as a reason for not joining a major international convention is a reminder of the high regard Iranian hardliners have for the country’s official anti-Baha’i policy.

A UNESCO-Bashing Habit

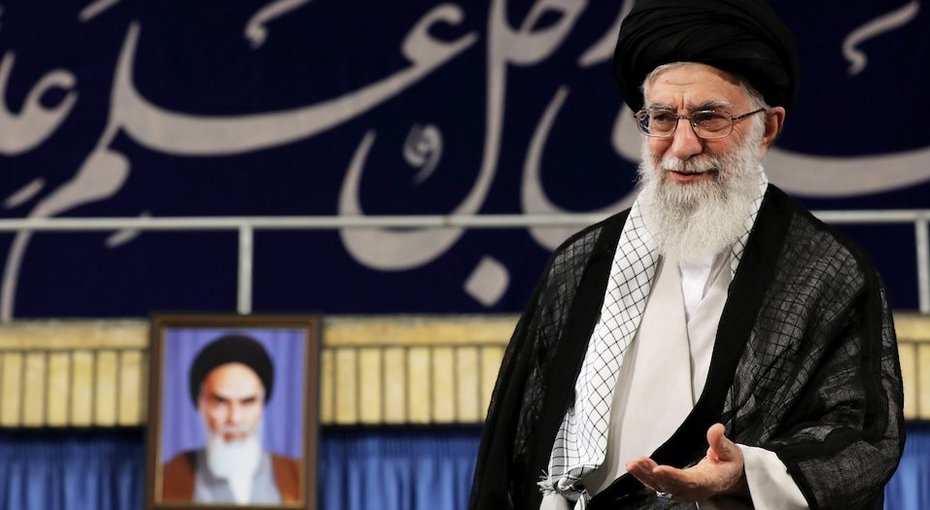

In his outburst against the convention on higher education qualifications, Zahedi also took the opportunity to compare it to another UNESCO initiative, Agenda 2030, which caused major controversy when Iran adopted it, culminating in a rare direct intervention by the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in 2017.

The initiative is part of the 17 sustainable development goals that every single member state of the United Nations, including Iran, agreed upon in 2015. The government of pro-reform President Rouhani had tasked the country’s education ministry to adopt a document on how Iran would reach the 2030 agenda set by UNESCO. But hardliners ran a sustained campaign against the decision. In February 2017, Hassan Rahimpoor Azghadi, a member of the High Council on Cultural Revolution (the HCCR, which is chaired by the president and sets the country’s cultural policies) claimed that UNESCO’s document “carries a liberal and neoliberal approach to children’s rights, education, women and family which, while having some commonalities with Islamic conceptions, also has fundamental contradictions with them.”

Earlier in the year, Sohrab Salahi, the head of the Basij’s university professors’ unit, had written to HCCR members warning that “American spies” had fooled the “simple-minded” Iranian authorities and were going to use the education plan to “destroy 5,000 years of Iranian culture and history.” Salahi didn’t give any reason for his grand accusations, but the hardline newspaper Kayhan did: “Centrality of gender equality, human rights and Western lifestyle” were the reasons it gave for denouncing Agenda 2030.

In May 2017, Ayatollah Khamenei directly intervened and repudiated the document. Speaking to a group of teachers during Teachers’ Week in Iran, he said: “This is wrong in principle. We can’t go and endorse a document and then start to slowly implement it. This is absolutely not allowed.” Khamenei rebuked the HCCR for having gone through with this in the first place and added: “They should have cared and not let it get it to a place that we have to step in. This is the Islamic Republic.” Shortly after, Iran’s foreign ministry spokesman Bahram Ghassemi reiterated his country’s policy: “No part of the UNESCO 2030 Agenda that is opposed to our cultural, religious, social and moral values will ever be implemented. Iran has no commitment to their implementation, and its principled and immutable stance has been declared officially to UNESCO and inscribed in the organization’s official website.” So the Supreme Leader single-handedly and successfully set the direction, discarding the patient work of diplomats who had contributed to the agenda.

As horrific cases of sexual abuse of children continue to rock Iran, many people have asked if the adoption of international standards like those inscribed in Agenda 2030 might not have helped. The battle between those who want to raise Iran to international standards and the custodians of its closed system rages on.

Leave a Reply