Source: iranwire.com

The Islamic Republic of Iran was born in 1979 following a wave of popular uprisings against Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The Shah’s policies were modernizing yet his regime was repressive; many Iranians felt his reforms were failing to reach them or were disrupting life for the worse. The Revolution was led by Muslim clerics and the founder of the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, was its first Supreme Leader. They drew their legitimacy from appeals to Twelver Shia Islam and weaponized existing prejudices against religious minorities to cement their position.

Under the new regime, tens of thousands of Iranians whom the regime found objectionable (whether because they posed a political or an ideological threat) were killed. This article looks at the experience of Iran’s Baha’i citizens who have been subjected to government-sponsored persecution since the Revolution.

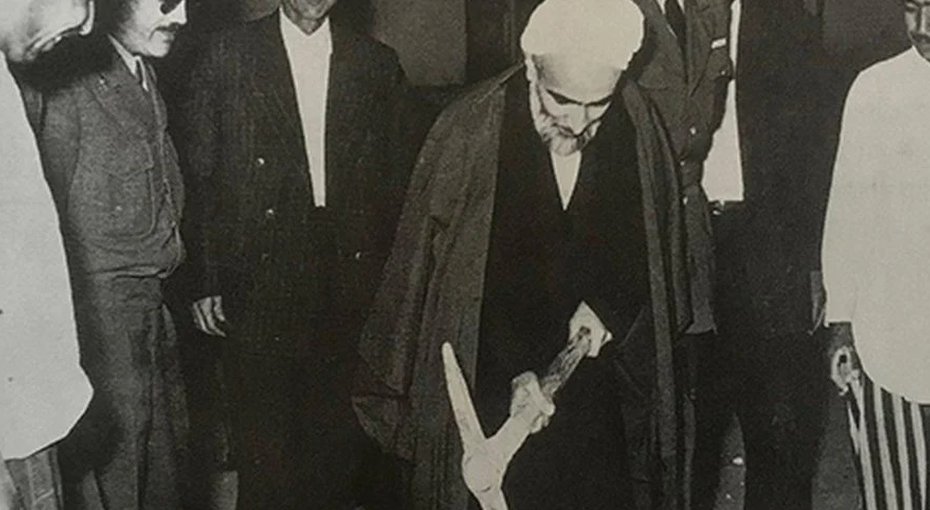

The Baha’i community has experienced various forms of persecution in Iran throughout its 160-year history: in sporadic incidents of violence in the first half of the 20th century, and later in legal and bureaucratic assaults. In 1955, the Shah allowed a populist cleric to preach against Baha’is on national radio, leading to mob violence, murders, rapes, robberies and the desecration of Baha’i property.

Baha’is endured localized harassment even during calmer periods of the Shah’s reign. Baha’i meetings were infiltrated and disrupted, Baha’i businesses were boycotted, Baha’i employees were dismissed and Baha’i children had stones thrown at them on their way to school and were humiliated by their teachers.

Clerics have led this persecution from the earliest days of Baha’i history. And with them now leading the new Islamic Republic government, the persecution increased by an order of magnitude and continues in systematic forms to this day.

Other religious minorities in Iran do not have the same rights as Shia Muslims, although they are recognized in the constitution; these include Christians, Zoroastrians and even Jews, notwithstanding the regime’s fierce anti-Zionist rhetoric and actions. But the existence of the Baha’i faith, as a post-Islamic religion founded in the mid-19th century, goes against the Islamic belief that Islam is God’s final religion.

A systematic campaign of government-sponsored persecution

Revolutionary courts were responsible for the 1980s show trials and executions of Baha’is. And a secret document – uncovered in 1991 by United Nations Special Rapporteur, Reynaldo Galindo Pohl, prepared that year by the Supreme Revolutionary Cultural Council and signed by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s Supreme Leader from 1989 to today – details measures for the “progress and development” of the Baha’is to be “blocked.”

More than 200 Baha’is were executed during the 1980s and early 1990s and a thousand or more were imprisoned. The arbitrary detention and jailing of Baha’is, on fabricated charges, continues today. So do the policies of barring Baha’is from higher education, forcing their dismissal and exclusion from employment, denying them business licenses or sealing their businesses, vilifying them in state media and even desecrating their graves. All communal Baha’i property has been confiscated, including holy places, some of which were destroyed. Refusal to grant identity cards and marriage certificates to Baha’is handicaps them socially and renders them as non-persons.

Genocide: a term forced into existence by the Holocaust

The Holocaust was the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators during the Second World War. The Nazis aimed to annihilate the Jews of Europe, whom they identified as a race, regardless of whether they practiced Judaism or identified as Jews. Nazi Germany also persecuted and murdered other minorities, including Roma, people with disabilities, Slavs, gay people, and Jehovah’s Witnesses, a religious minority in Germany.

Learning how and why the Holocaust happened is essential to the understanding – as global citizens and as an international community – of genocide, crimes against humanity and the potential for prevention. “Never again” was the cry taken up by ordinary people and statesmen when the horrors of the concentration and death camps in German-dominated Europe became known after the war. The UN drew up and approved a Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which came about, it said, because “the international community vowed never again to allow atrocities like those of that conflict to happen again.”

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was meanwhile adopted by the UN General Assembly, in 1948, born of the same determination to never allow atrocities such as those committed during the Second World War to return.

But despite these commitments, and the appearance of warning signs, the world did not prevent several later instances of genocide. These included the Anfal genocide in Iraqi Kurdistan that saw up to 100,000 Kurds killed on the orders of Saddam Hussein, the slaughter of 800,000 to a million Tutsis in Rwanda by Hutus in 1994, and the murder of about 8,000 Bosnian men and boys at Srebrenica in 1995 by Serbian forces.

The international effort to prevent genocide relies on identifying patterns that could lead to genocidal acts. At times, some of these patterns can be identified in the case of the Islamic Republic’s treatment of Iran’s Baha’i community.

UN Definition of Genocide

The UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide – which was based on the work of Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jewish lawyer who had lost family members in the Holocaust, and who coined the term “genocide” – defines it as any of the following acts “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:”

“(a) Killing members of the group;”

“(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;”

“(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;”

“(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;”

“(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Several scholars have looked at this record of the systematic government-sponsored persecution of Iran’s Baha’i community from the viewpoint of the definition of genocide and the existence of its warning signs. The International Commission of Jurists stated in 1982, for example, that the “treatment of Baha’is is motivated by religious intolerance and a desire to eliminate the Baha’i faith from the land of its birth. This comes close to an allegation of genocide.”

Warning Signs: State Persecution of Baha’is Since 1980

a) A campaign of vilification and dehumanization

Helen Fein, a sociologist, former associate of the International Security Program and executive director of the Institute for the Study of Genocide at City University New York, has identified, as a risk factor for genocide, the rise of a new elite along with the creation of a hegemonic myth that idealizes the dominant community and seeks to place the victim group outside the state’s legal obligation to protect and serve.

The narratives of the Islamic Republic present the dominant Shia community as a mythic nation against which the world is arrayed. This paranoid perspective has bred conspiracy theories, promoted by Iran’s leadership, that claim every misfortune befalling the nation is the result of malign “outside” forces. Khomeini’s denunciation of the West’s cultural imperialism and political arrogance was at the heart of his appeal; within this, the Baha’i community was turned into the “enemy within,” allied to external enemies, seeking to overthrow the Islamic Republic and Islam.

Iran’s Baha’i community has thus been subjected to attacks from clerical leaders and state-controlled media. They are accused of being agents for enemy powers, such as the United States and Israel, and of being responsible for the worst excesses of the former Shah’s regime, despite being its victims. Baha’is have even been accused of sacrificing Muslim children in secret ceremonies. A study by the Baha’i International Community found that more than 26,000 pieces of anti-Baha’i propaganda have been disseminated by Iranian media during current President Hassan Rouhani’s administration.

b) Risks to a community increase during a state of war

Helen Fein also notes that the costs or risks to the state of initiating a genocide diminish if it enters into a conflict against another state. War reduces the deterrents to genocide by obscuring “the visibility of such actions,” and provides perpetrators with justification by accusing the victims of assisting the enemy.

The Islamic Republic began life with an ideological conflict with the United States, Britain and Israel, then an actual war with Iraq. Iran has also been engaged in proxy wars in Lebanon, Syria and Yemen, and confrontations in the Persian Gulf. It’s theorized that war heightens perceptions of threat from certain groups and “normalizes” violent responses, which may facilitate the Iranian government’s persecution of the Baha’is.

c) Persecution is endorsed and ratified by all arms of government

Israel Charny, editor of the Encyclopedia of Genocide and executive director of the Institute on the Holocaust and Genocide in Jerusalem, says a final stage on the path to genocide is reached when a state openly endorses and ratifies attacks on the victim group.

This has been the case for the Baha’is under the Islamic Republic. National leaders – from the supreme leader, president and senior judges and police chiefs – have all publicly denounced the Baha’i community. Many have called for its elimination from Iran. Khomeini called Baha’is “dirty” and asked his followers to shun them. And in 2016 his successor, Ali Khamenei, called Baha’is “dirty beings who are against your religion” and also asked his followers to avoid contact. Iranian police therefore do not prevent or apprehend those who attack Baha’is. Courts refuse to issue judgments against the perpetrators of anti-Baha’i crimes. Religious leaders give their blessing and legitimize these acts by dehumanizing the victims and promising their followers a heavenly reward for their actions.

International Pressure on Iran to Relent

The persecution and killings of the Baha’is during the early Islamic Republic might have escalated to genocide since the international community had little understanding of the situation. But a campaign in the 1980s, mounted by the Baha’i International Community, or BIC, a non-governmental organization that represents the Baha’is at the UN, called on Iran’s government to moderate its actions and helped to spur international action.

Gerald and Margaret Knight, two British Baha’is who managed the human rights portfolio of the BIC, coordinated the campaign.

“Government representatives and UN Secretariat personnel weren’t interested at first. It just wasn’t important,” says Gerald Knight. “They didn’t know much about the [Baha’i] faith, they didn’t know anything, really, until we started to explain to them what was happening to the Baha’is in Iran, and why. We had to convince them.”

The BIC presented documentary evidence of the violence engulfing Iran’s Baha’i community. Margaret Knight says Iranian diplomats to the UN would “deny, deny, deny” that anything was happening, while also making false allegations against the Baha’is such as “accusing the Baha’is of being a political organization” and of being “anti-Islam, agents of Israel, tools of colonialism [and] supporters of SAVAK,” Iran’s secret police during the reign of the Shah.

Despite this, and with the advocacy of Baha’i communities in several countries, in 1980 the BIC secured the first resolution on the Baha’is in Iran, from the UN’s Sub-Commission on Human Rights. The resolution stated that the Sub-Commission “expresses its profound concern for the Baha’is, both individually and collectively, and invites the Government of Iran to protect their fundamental human rights and freedoms.”

The UN would go on to adopt other, more detailed resolutions on the protection of the Baha’is each year (except for 2002) from 1981 to 2015.

Days after the first resolution was passed, the European Parliament, representing citizens of the European Community, also took action. Baha’i representatives in Belgium, Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and West Germany had contacted their governments, briefed them on the situation, and requested that the European Parliament call for the human rights of the Iranian Baha’i community to be respected. The parliament passed its resolution on 19 September, 1980, which then “rippled back to governments,” Gerald Knight says.

Margaret Knight adds: “Although these were positive developments, they didn’t stop the persecutions, so the BIC took steps to make the situation of the Baha’is more widely known and more fully understood.”

A major step was the BIC’s 1982 publication The Baha’is in Iran: A Report on the Persecution of a Religious Minority, which documented the persecutions, examined their historical background and motivation, refuted false charges leveled against the Baha’is and explained Baha’i teachings and beliefs. Published in English, French and Spanish, the document was circulated to national Baha’i institutions around the world and was shared at the United Nations, where it became the standard reference document on the Baha’i case.

Ongoing action by the BIC and national Baha’i communities resulted in a case citing Iran by name being taken up during the March 1982 session of the Commission of Human Rights – then the UN’s primary human rights organ.

“While the resolutions of the Sub-Commission and European Parliament had helped the Baha’i issue to be taken more seriously at the UN”, says Gerald Knight, “raising a country-specific resolution at the Human Rights Commission was rare. In those days, it wasn’t the done thing to talk about governments. It wasn’t considered appropriate. [The sentiment was that] what states did with their own citizens was a matter for their internal decision-making and the international community was not supposed to interfere.”

Controversy among UN member states over country-specific resolutions continues today. Many states, such as Iran, reject the idea that the UN’s human rights mechanisms and resolutions should cite specific countries by name.

Nevertheless, in March 1982 the Commission adopted its first resolution on the Baha’i case. The resolution noted the “perilous situation facing the Baha’is in Iran” and called on the UN Secretary-General to “establish direct contacts with the Government of Iran … and continue his efforts to ensure that the Baha’is are guaranteed full enjoyment of their human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

Shortly after the resolution, but with the persecution continuing, Gerald Knight was asked by eminent sociologist Leo Kuper, who believed the situation unfolding in Iran was at risk of becoming a classic case of genocide, to speak at a Symposium on Genocide in London and to describe what was happening to Iran’s Baha’i community and why.

“It took us until 1985,” Gerald Knight says, “to actually secure a resolution at the [UN] General Assembly [representing all UN member states]. That was possible, for the first time for any specific group, because the worldwide Baha’i community used its evidence about the actions of Iran’s government, distributing the information from its UN office to others in the international community, so that they could raise the issue with national government officials and representatives.”

“Individual Baha’is and Baha’i groups were approaching their MPs,” Knight adds. “MPs were raising the issue in their national parliaments and with their ministries of foreign affairs, and that all resulted in the word going to New York to look at this seriously. So we at the BIC weren’t doing it alone. We would never have been able to do it if it had just been us.”

On December 13, 1985, “history was made,” Gerald Knight says, when a resolution was adopted stating the General Assembly’s “deep concern over the specific and detailed allegations of violations of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran” and that the body would “continue its examination of the situation … including [that of] the situation of minority groups such as the Baha’is”.

Gerald Knight says this was “the first time the General Assembly had ever adopted a resolution about the human rights situation in Iran or about the particular situation of the Baha’is … it was unprecedented.”

The executions of Baha’is in Iran in the early 1980s tailed off. But the persecution continued and still continues today, by other means; policies such as the denial of the right to access higher education and work, state-sponsored public vilification, and arbitrary detentions and jail sentences on fabricated charges, are facts of life for Iran’s Baha’i community.

Interviews by Saleem Vaillancourt

This article was produced by IranWire as part of The Sardari Project: Iran and the Holocaust, a project of Off-Centre Productions and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Leave a Reply