The new Revolutionary government announced the executions in a press conference, cloaking them in a litany of fabricated charges: that Baha’is were spies, thieves and foreign stooges. While these accusations were transparently ludicrous, the bald admission of the killings of the Baha’i leadership was serious. It signaled with bracing cruelty and shamelessness the sort of welcome Baha’is could expect in Revolutionary Iran.

Since I married into the Samimi family six years ago, I have been searching for Kamran, drawn inexplicably to him and the nature of his death with a force that sometimes surprises me. What is it I am hoping to learn from him?

The naked facts about his life sometimes hide more than they reveal. He was born in 1926, he lived in Jakarta for some years, teaching English. He dressed colorfully, he enjoyed jazz music, he was tall and good-looking. But all these details don’t add up to justify my interest in him. The stories I hear tell me a little more.

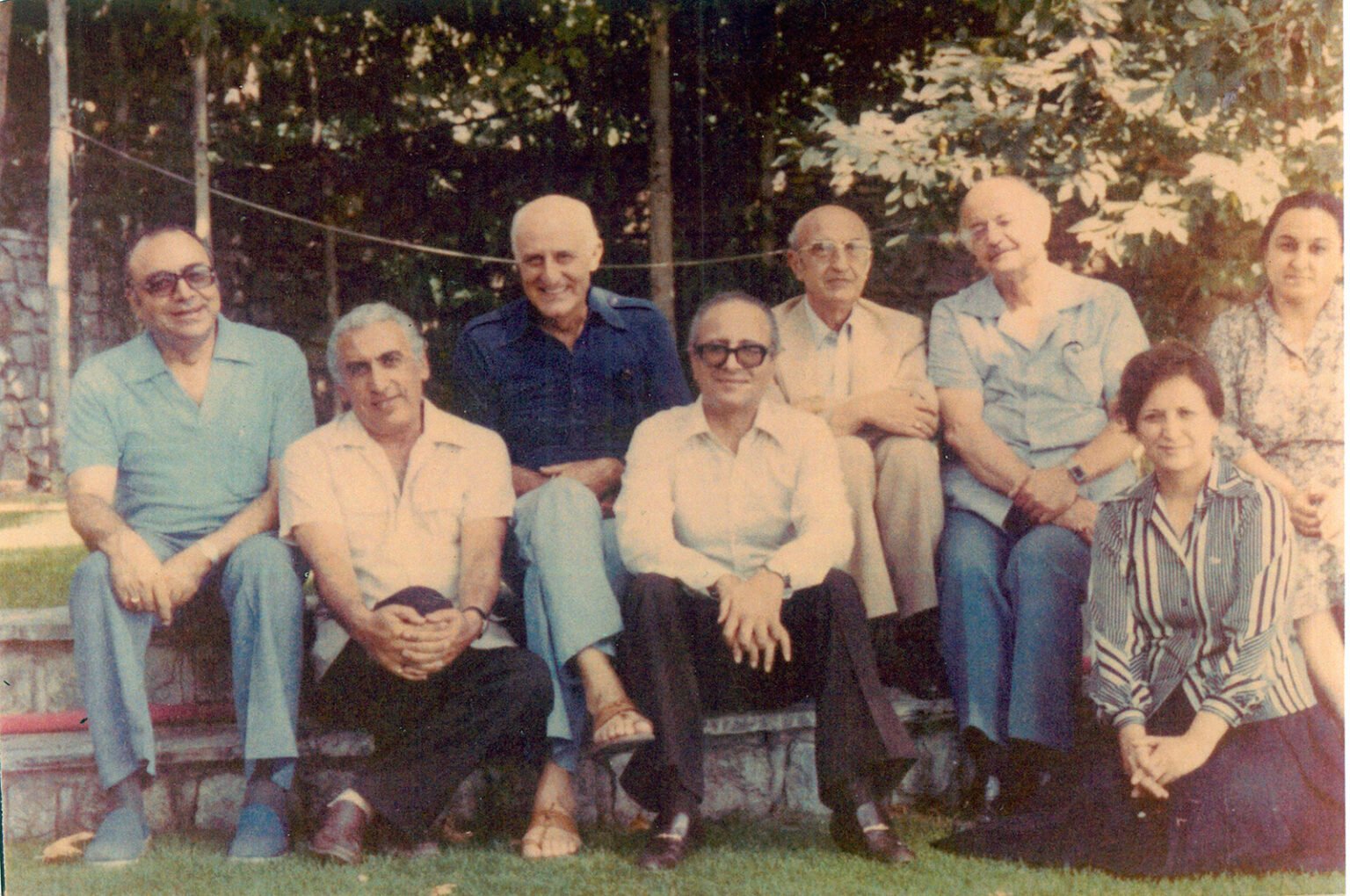

At an Assembly meeting, he and his colleagues were consulting about how to protect their community, already under heavy duress from executions, vigilante violence and imprisonments. On a break at the pool outside, to cut the tension, this dignified man astonished everyone by jumping into it fully clothed — successfully inducing everyone to laugh.

I learn the most, though, when I zero in on his last days, which have been preserved through loved ones and others who are similarly drawn to his memory.

I spoke recently with the sole surviving member of his Assembly, Guiti Vahid. Late one night, she received a call that more Baha’is had been executed in the city of Shiraz. In keeping with perverse custom, the Baha’is had been killed on the eve of one of our Holy Days, in an effort to spoil the festivities for the community and sap morale. She laid awake with the news for several hours before deciding to call Kamran. Though it was late, he answered instantly and listened intently as she shared the news.

“Guiti,” he said, “let’s keep this horrible news between us, just for today, for the sake of our colleagues.” The day passed excruciatingly slowly, but Kamran wanted his friends at least to be able to enjoy the festivities. “Let them, at least,” he said, “have their Holy Day.”

A video improbably exists of the Assembly’s trial, lost for years only to resurface recently. Kamran sits upright alongside his companions, the poor picture quality stripping its realism to the point it seems to resemble a painting more than a film. The key to his freedom is simple. He only needs to recant his beliefs, and he would be set free.

At some point, during whatever happened to him in those last days in Evin Prison, I wonder, was he tempted? In the footage, Kamran smiles inexplicably through the vicious accusations. They interrupt him frequently as he calmly picks apart their falsehoods. His nerves, almost certainly tested through torture, only show forth in the slight tic of touching his face with his fingers. Hours after the camera cuts, he is dead, buried without honor or ceremony.

This is what adherence to principle looks like. It’s selfless, courageous and ultimately, transcendent, because it takes us to the breaking point of what we think is possible, and then pushes further.

Iranian Baha’is today carry on this legacy of moral fortitude. They endure arrests, imprisonment, torture, economic deprivation, land expropriation, denial of higher education and other state-sanctioned forms of persecution. Far from buckling under this pressure, the community continues to practice its teachings of service to humanity, believing fully, even if their government does not, that they are full citizens, loyal to their country and its inhabitants.

As I watch the grim carousel that is the nuclear talks go round and round again, I think about all that may hinge on them, including, perhaps, the future of Iran’s religious and ethnic minorities, who often serve as scapegoats for the Iranian regime’s diplomatic and economic failures.

Despite international censure and repeated evidence of growing popular dissatisfaction, it has made no fundamental adjustments and remains committed to the same ideology that justified the killing of Kamran 40 years ago and continues to justify the persecution of Baha’is and other minorities.

Could our leaders say they lived up to our principles if a nuclear deal does not consider such human rights abuses? Kamran’s story illustrates the difference between those willing to kill for an idea and those willing to die for one.

It must not be forgotten.

(James Samimi Farr is a writer and Baha’i living in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Leave a Reply