Source: iranwire.com

Kian Sabeti

Health workers are on the front line of our defense against the coronavirus pandemic – including hundreds of Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. But they are not in Iran; instead, they live in countries around the world, treating their patients, where they are admired and praised by the people and governments of the countries where they live. The one country where they cannot do their work is Iran.

Many of these doctors and nurses – who studied and served in Iran – lost their jobs after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. They were expelled from the universities and their public sector jobs, barred from practicing medicine, jailed and tortured, and a considerable number of them perished on the gallows or in front of firing squads.

The crime of these Baha’i doctors, nurses and other health workers was their faith in a religion that the rulers of the Islamic Republic believe is a “deviant” faith.

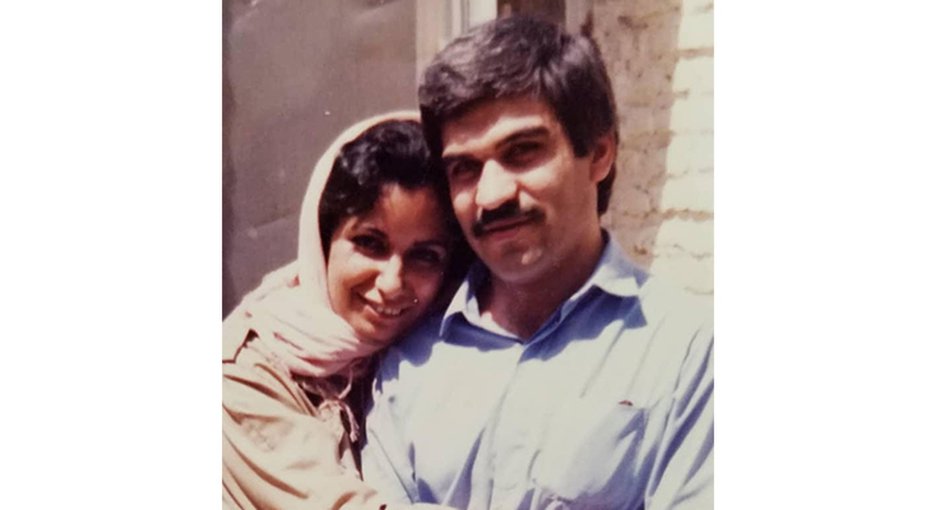

In a new series of articles, called “For the Love of Their Country,” IranWire tells the stories of some of these Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. The following is the story of Dr. Sina Hakiman and Dr. Sholeh Misaghi, a married couple who spent their lives together in Iran trying to practice medicine despite experiencing discrimiantion and even prison after the Revolution.

If you know a Baha’i health worker and have a first-hand story of his or her life, let IranWire know.

Dr. Sina Hakiman and his wife, Sholeh Misaghi, have been living in the United Kingdom for 15 years. They live a quiet life and have been able to specialize in their respective medical fields. Dr. Hakiman retired and spends his days studying, researching and translating. Dr. Misaghi works two days a week at a hospital famous for its skin and cosmetic services.

Fifteen years ago, these two Baha’i doctors went to the UKfor family visit. On the day they were leaving for their homeland, Iran, a relative informed them that Sina Hakiman’s life was in danger and security agents were looking for him.

They loved their country and had remained in Iran through the 1979 Islamic Revolution and after, then despite all the hardships that had been imposed on them for half a century.

Sholeh Misaghi (Hakiman) was born to a Baha’i family in Tehran. She was only five months old when her father, Dr. Amanullah Misaghi, an army doctor, was transferred to Ahvaz, and the family moved to Ahvaz with the father.

She spent her elementary and high school years in Ahvaz. Misaghi passed the medical exam and entered Pahlavi University of Shiraz in 1974 and graduated in 1981. Dr. Sholeh Misaghi married Dr. Sina Hakiman in November 1960.

According to Iranian law, medical graduates were required to fulfill their medical obligations and complete an out-of-center service program after graduation before they could obtain a permanent license. But the Ministry of Health and Medical Education did not allow Sholeh Misaghi to enter the program because she was a Baha’i. At the same time, they refused to give her the medical degree because she had not completed the program.

At that time, and due to the community’s need for women doctors, a law was passed that allowed women doctors to open private clinics in disadvantaged areas. Dr. Misaghi was denied this legal right as well, because the government did not recognize her Baha’i marriage and told her that she could only take advantage of the law if she went through an Islamic marriage. Dr. Misaghi was also barred from continuing her studies to take a medical specialty.

Her husband, Dr. Sina Hakiman, was born to a Baha’i family in Kerman in September 1943. His father, Tarazullah Hakiman, was an employee of the Assets Department of the Sugar Organization. Sina was two years old when he moved to Zahedan with his family. He went to school in Chabahar, Iranshahr and Kerman and received his diploma with honors in Zahedan.

In 1971, 18-year-old Sina was accepted in the entrance exam of Pahlavi University of Shiraz with a single-digit rank in medicine. Dr. Sina Hakiman graduated from Shiraz University in 1979. Dr. Hakiman’s education took several months longer than his classmates as he studied at a university in Winnipeg, Canada for eight months in 1978, where he studied internal medicine,

He returned to Iran after graduating in Canada just as the Islamic Revolution in Iran reached its peak. Many of his friends in Canada advised him to not return to Iran. But Dr. Hakiman, insisting on his medical commitment to Iran and his interest in serving his homeland, returned to Iran in September 1978.

He was sent to military service. At the Ajabshir garrison, all doctors on duty were allowed to also hold private clinics; but Dr. Hakiman did not have this privilege because he was Baha’i.

Dr. Hakiman later applied to be transferred to Balochistan to be closer to his family because of his father’s stroke. Eventually, his request was granted and he was transferred to the city of Khash. With the start of the Iran-Iraq War, the 1.5-year military service was extended for a six-month period. After completing his regular military service in Khash, Dr. Hakiman was able to serve the six-month additional period in Zahedan.

Dr. Hakiman experienced more discrimination in Khash. The head of Khash Medical Center at the time, Dr. Rezaei, was friendly with the anti-Baha’i Hojjatieh society and used his position to harass Sina Hakiman. In addition to not allowing Dr. Hakiman to have a private office, he also asked the pharmacy to not accept prescriptions signed by him. His purpose was to deprive Dr. Hakiman of the few patients he might have had at a home clinic.

The restrictions imposed by Khash Medical Center on Sina Hakiman coincided with the news of the abduction of Dr. Ali Murad Davoodi, a Baha’i philosophy professor and author, who was highly regarded by Dr. Hakiman.

“These two events,” Dr. Hakiman told IranWire, “the kidnapping of Dr. Davoodi, a person with high academic status, and me not being allowed to have a private office, prompted me to ask for justice from the same government that was the source of this oppression and discrimination, because I was a law-abiding citizen. My first correspondence, which was the beginning of a series of correspondences I had with the country’s officials, from Ayatollah Khomeini to other officials, began in Khash. I wrote a letter to the Director0General of Health of Sistan and Baluchestan province, complaining about Dr. Rezaei’s discriminatory behavior, and asking for the right to have an office like any other medical graduate.”

After completing his military service, Dr. Sina Hakiman went to the Ministry of Health and Medical Education to perform his obligatory medical services. The Ministry informed Dr. Hakiman that because he was a Baha’i, he could not be paid from the official treasury, so he was not able to fulfill his obligation; and because he could not fulfill his obligation, he would not be granted a permanent medical license, which is required for a doctor’s office.

Getting Married and Being Advised to Leave Iran

After completing his military service in 1981, Sina and Sholeh married and decided to live in Tehran where it was easier to pursue their rights as Iranian citizens.

Once they settled in Tehran, the Baha’i couple wrote more than 100 petitions to 15 Iranian officials and legal authorities, including Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Revolution and the Islamic Republic’s first Supreme Leader, the secretary of the Guardian Council, the president, the prime minister, speaker of the Assembly of Experts, speaker of Parliament, and chairman of the Supreme Judicial Council, the Court of Administrative Justice, the inspector general of the country, the minister of health and the Medical Council. The petitions focused on three issues: the lack of the permission to practice medicine and to have a clinic, the denial of their Baha’i marriage, and barring Baha’is from continuing education and getting medical specialties.

Sina Hakiman met with the then Minister of Health, Dr. Hadi Manafi, seven times. Dr. Hakiman said that during the first meeting, the minister told him that the Baha’is in Iran were like mouse dung in a bag of rice. Dr. Hakiman quoted the minister in his petitions. This made Dr. Manafi softer in subsequent appointments. He suggested to Sina to get a passport and to leave Iran. In those years, passports were not issued to Baha’is. In response, Dr. Hakiman told IranWire that he responded by saying that he, like any Iranian citizen, had the right to have a passport and permission to leave the country, but that “Iran belongs to Sina Hakiman as much it does to you (the Minister of Health) or Mr. Khomeini. No one is allowed to deport a fellow citizen from their homeland.”

Since the couple did not have their medical license to open an office, they had to work in clinics in Tehran. Initially, Dr. Hakiman worked part-time at the Vanak boarding clinic at nights, and Dr. Misaghi practiced at a clinic in Chahardangeh, Islamshahr, for one-third of a doctor’s salary.

Arrest of Sina Hakiman and Forced Work in Prison

In the early summer of 1962, about a year and a half after the couple moved to Tehran, Dr. Hakiman worked at night at a clinic on Saveh Road. On the morning of June 27, he returned home after finishing his night shift; upon entering the house, he noticed that it was in disarray. After some investigation, he learned that his wife, two sisters, and his father had been arrested by security agents, led headed by a person named Mesbah, from Branch 42 of the Revolutionary Court of Tehran. He immediately presented himself to the Revolutionary Court so that his family who had been taken as hostages could be released. His wife and sisters were freed but his father remained in custody on charges of following the Baha’i faith, and was sentenced to three years imprisonment, the confiscation of his past salary payments and the termination of his pension.

The Islamic Revolutionary Court of Tehran, presided over by Judge Seyyed Asghar Nazemzadeh, sentenced Sina Hakiman to 10 years medical work in prison on charges of “active membership in the deviant Baha’i faith,” 129 days after he was arrested. Sina Hakiman is the only Baha’i physician to be sentenced to medical work in prison by an official order. The sentence was issued while he had been deprived of practicing medicine and having a clinic.

Transfer of Sholeh Misaghi to Isfahan

After the arrest of Sina Hakiman, Sholeh Misaghi spent two nights a week in a children’s hospital in south Tehran to make a living, but this alone was not enough to support her. She wove baby shoes on the way from home to the hospital and sold them for extra income. In a few months, Dr. Misaghi was no longer able to pay the rent. She moved to her father’s house in Isfahan in 1963 where she did not have to pay rent. She still followed up on the petitions through the Medical Council.

It was during these trips to Tehran that Dr. Misaghi was informed by Tehran’s Medical Council that, according to a new order issued to another Baha’i named Dr. Heshmatollah Behshad, she could also open her own private clinic in one of the underserved locations of the country. Dr. Misaghi chose the hometown of her parents, Dehaghan, in Isfahan province.

Dr. Misaghi’s office in Dehaghan, which was located between the Dehaghan seminary and the local mosque, was always full of patients, most of whom were women. Among the patients were a large number of women who were the wives of city officials or Islamic religious students. Although everyone knew she was a Baha’i, she was so trusted and loved that her patients even invited her to their homes for lunch or knocked on her door in the morning and asked to do her shopping. When Dr. Misaghi was preparing to leave Dehaghan, after three years of medical service, she had become so popular that a number of locals insisted on her staying.

Finally, after fulfilling her medical obligations, Dr. Misaghi left Dehaghan for Shahinshahr, Isfahan. She was now allowed to set up a clinic. When her clinic was first opened, few patients came. The Social Security Organization was reluctant to sign a contract with her because she was Baha’i and patients wanted to go to a doctor with a contract so they could use their insurance to pay the costs. Sholeh had to travel around Isfahan to practice medicine to earn a living.

Dr. Hakiman’s Account of Prison

In early December, Dr. Hakiman was transferred from Qasr Prison to Ghezel Hesar Prison. Haj Davood (Rahmani) was the head of Ghezel Hesar prison; at that time, Ghezel Hesar Prison had three units, two for Revolutionary Court prisoners and one for others. Dr. Hakiman was ordered to take charge of medical services in the units serving Revolutionary Court detainees and was also held in one of these units.

At that time, Dr. Rousta, a tawab (repentant), a political prisoner converted to Islam under pressure of prsion officials and interrogators, was also a prison doctor who had his room separated from Dr. Hakiman due to an order that considered Baha’is “unclean.”

Dr. Hakiman said that each prison unit consisted of a number of wards and cells, and that many prisoners were held there; for example, in some solitary confinement cells, there were 50 or 60 prisoners who did not even have a place to sit.

Under these circumstances, he was responsible for the health of people who were under physical and mental duress and lacked proper health and nutrition. The prison warden did not have a humane view of the prisoners, and if someone died of an illness, they would say, “They have gone to hell.”

Many prisoners were being tortured at the time, and Dr. Hakiman, seeing the dire condition of the prisoners, requested that they be sent to hospital. But the prison officials refused to send them. The officials wanted the doctor to take responsibility if these prisoners died under torture and to provide causes of deaths. Dr. Hakiman did not comply with this request.

As the dispute between the prison warden and Dr. Hakiman escalated, he was transferred from the prison’s health center to ward six of unit three. Twenty-five prisoners lived together in a solitary cell measuring about 1.60 meters by 2.80 meters.

In the early summer of 1963, the prison warden Haj Davood and his colleagues were fired and replaced by a man named Meysam. He did not want Dr. Hakiman to practice medicine in prison. Dr. Hakiman was later transferred from Ghezel Hesar Prison to Gohardasht Prison in Karaj.

In late 1963, Baha’i prisoners were transferred from Ghezel Hesar Prison to Gohardasht Prison. A few days after the Baha’is arrived in Gohardasht Prison, Mortazavi, head of the prison, in his first meeting with Dr. Hakiman said, in a harsh tone: “We have creatures in this prison that live in these cells and holes and they have a headache every once in a while. We want a doctor in the health center who can keep them under control.”

Dr. Hakiman replied he would treat them as patients – as any other person. The head of the prison left the meeting in a rage.

After working at Gohardasht Prison for several weeks, Sina Hakiman requested to be transferred to Zahedan prison due to his father’s health issues. He was transferred two months later.

Initially, Zahedan Prison was under the control of the police, but towards the end of Dr. Hakiman’s time it was handed over to the Office of Prisons and the Revolutionary Court.

Dr. Hakiman says he felt calm and comfortable when the prison was under police control. The police prison authorities did not ask him to violate medical ethics and only asked him to treat patients as a doctor. He and another Baha’i friend, Fedros Shabrokh, who had become the director for the prisoners, had created a calm and clean environment in the prison’s health center, with prisoners saying that when they entered the hospital, they seemed to be in a different environment than the prison. Fedros Shabrokh was executed in Zahedan Prison in 1965 on charges of following the Baha’i faith.

Once the Revolutionary Court took charge, even though he was sentenced to work as a doctor in prison, Dr. Hakiman was barred from practicing medicine and was transferred to a ward. Dr. Hakiman was in Zahedan Prison utill 1965. After his father was released, he applied for a transfer to Isfahan Prison. He was transferred to Dastgerd Prison in Isfahan in the same year.

The head of Dastgerd Prison was a man named Tutian. By his order, Dr. Hakiman’s carried out his sentence to work as a doctor but his duties and responsibilities were minimized. This situation continued until the summer of 1988.

All prisoners, including Dr. Hakiman, were banned from receiving visits. During this period, groups of prisoners were tortured and handed over to execution squads. Dr. Hakiman still remembers the faces of some of the tortured prisoners in Isfahan Prison’s health center. Those few months were one of the most difficult periods of his imprisonment. He was not allowed to receive visits and he knew that his wife was worried about his condition. At the same time, as a doctor, he was not able to help young people who were tortured or sentenced to death.

Dr. Hakiman was transferred from Isfahan to Evin Prison for unknown reasons in October 1988. The sudden transfer, which coincided with the mass execution of political prisoners, worried his wife. In March 1967, a large number of Baha’i prisoners were released from Iranian prisons, and Sina Hakiman was released from Evin Prison on March 5, after serving five years and eight months.

Serving in Larestan, Fars Province

After he was released, Dr. Hakiman went to the city of Evaz in the Larestan region of Fars province with his wife, Dr. Misaghi, to continue fulfilling their medical obligations. The couple quickly became popular and decided to continue working there after their obligations were complete.

One of the main reasons for the couple’s popularity as doctors were their efforts to prevent and treat a parasitic disease called Giardia. The people of Evaz used water reservoirs due to the lack of fresh water at the time, which led to the spread of Giardia parasites among the residents. The couple diagnosed the disease and found the cause of its prevalence in the area, treated it and also educated people about prevention methods.

Attending local ceremonies, practicing medicine, and having a positive track record, also because of the presence of another Baha’i physician, Dr. Kanaani, gave the locals great confidence in this couple.

After a few months, Dr. Hakiman and Dr. Misaghi became the neighborhood doctors and made many family friends. A new doctor was sent to Evaz after about two years, who tried to draw patients from Dr. Hakiman and Dr. Misaghi using any means. When the doctor failed to recruit their patients, he reported to the Fars Health Organization that the couple living in Evaz were Baha’is. By an order from the Health Organization, the couple lost their right to practice medicine in Evaz and were fired. They were expelled from Evaz even as the townspeople petitioned for them to stay. They were so popular in Evaz that even after three decades, many townspeople are still in touch with them.

The Trials and Travails of a Baha’i Couple in Iran

Under pressures from the Health Organization in Fars province, the doctors moved to Zahedan in 1991. Threats by unknown individuals forced them to migrate again, to Isfahan, the residence of Dr. Misaghi’s family, after two years. Their home, which was in the name of Dr. Misaghi’s father, was confiscated by the Mostazafan Foundation in 1994, and they had to rent a new home.

None of the health and social security insurance companies signed contracts with Baha’i physicians in Isfahan province, and the Ministry of Health and Medical Education did not respond to any of the complaints made by the Baha’i physicians. Dr. Hakiman took on holiday work and night shifts in private hospitals such as Mehregan, Sina and Sepahan. Dr. Misaghi worked as a general practitioner in other clinics.

Security forces raided a Baha’i religious meeting in the city of Isfahan on October 8, 1998, arresting four of the attendees, including Sina Hakiman. The trial court sentenced Dr. Hakiman to 10 years in prison and the other three Baha’is to a total of 17 years in prison. But the appeals court acquitted all four prisoners, and after 14 months, Dr. Sina Hakiman and the three other Baha’is were released from Isfahan Prison.

In the summer of 2004, Isfahan intelligence agents visited the Hakiman family’s home and arrested the Baha’i couple and several other Baha’is. Dr. Misaghi was released a few hours later. Dr. Hakiman was released on bail after 48 hours in detention.

A year later, they traveled to the United Kingdom to visit relatives of the Misaghi family. They left Iran for the UK in May of 2005: they had no idea it would be the last time they saw their homeland. Two weeks before returning to Iran, when they had already bought their return tickets, a relative informed them that agents from the Ministry of Intelligence were looking for Dr. Hakiman and that his return to Iran would be suicidal.

The couple decided to stay in the United Kingdom. After passing medical exams, Dr. Sholeh Misaghi successfully completed a one-year course in dermatology, which had always interested her, but was banned from studying in Iran. Dr. Sina Hakiman also completed a two-year course in psychotherapy and worked in the field of psychiatry.

Dr. Hakiman and Dr. Misaghi are proud of being Iranian. They look forward to the day when they can serve the people of their homeland without any obstacles or problems; although, according to one of them, serving human beings does not require a specific time and place, but serving the good people of Iran has a special place in their hearts.

Leave a Reply