Source: www.iranwire.com

By SEAN NEVINS

In 1961, a young immigrant by the name of Hussein Ahdieh arrived in New York Harbor aboard the RMS Queen Mary, an ocean liner carrying over 1,000 other passengers. He arrived in America after having left the small impoverished town of Nayriz in the south of Iran. He left his home country because his family was persecuted for being members of the Baha’i Faith, a religion that emphasizes the importance of education, the harmony between science and religion, and the equality of men and women.

Having arrived in New York with very little money, Ahdieh took up jobs on assembly lines at various factories, washed dishes at restaurants, and sometimes had to sleep outside because he couldn’t afford a room.

Within six short years, however, Ahdieh became the Assistant Headmaster at an innovative new free school called Harlem Preparatory School, located on 125th Street and Seventh Avenue, in the heart of Harlem, which was buzzing with a revolutionary flair.

Today, Ahdieh’s homeland still discriminates against the Baha’is. Bahai’s face threats of arbitrary arrest, sporadic acts of arson, and have even been murdered by vigilantes likely backed by the state. They are also banned from teaching at or attending university.

IranWire’s founding editor-in-chief Maziar Bahari launched the Not A Crime campaign in 2014 to shine light on this injustice. The campaign is in Harlem this summer, commissioning 15 murals that expose human rights violations against the Baha’is in Iran. But the campaign did not just came to Harlem to expose what is happening in Iran but, also to learn from the experiences of the civil rights movement in the United States.

The Harlem Preparatory School, which was run from 1967 to 1977, represents one such case.

A group of black ministers, Catholic nuns, and Baha’is set up Harlem Prep, according to Ahdieh, who has published a book, co-authored by Hillary Chapman, about the school, A Way Out of No Way: The Untold Story of the Harlem Preparatory School. The school was founded to prepare high school drop-outs for college and careers during the era of 1960s idealism, which was ushered in by the civil rights movement.

“The big problem in those days, and it still it is, was the subject of drop-outs,” Ahdieh told IranWire. “A large number of minorities never finished high school,” he said. The book details how dropouts in 1960s and 1970s Harlem were sometimes referred to as “force-outs” — referring to the patronizing way the public education system treated many of its students, which in some cases forced them to drop out. Harlem Prep was trying to provide an answer to this dilemma, explained Ahdieh. “It [the school] proved it can be successful if you come up with the right formula, and have the resources, and both the kids and yourself are really committed,” he said. In its first year of operation, Harlem Prep graduated 100 percent of its 71 students, and all of them went on to college.

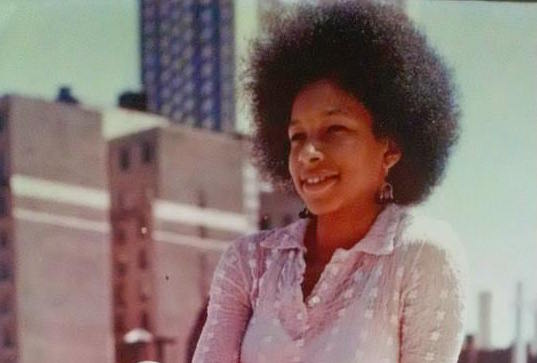

Lorelei Fields, a Harlem Prep graduate in the Class of 1970

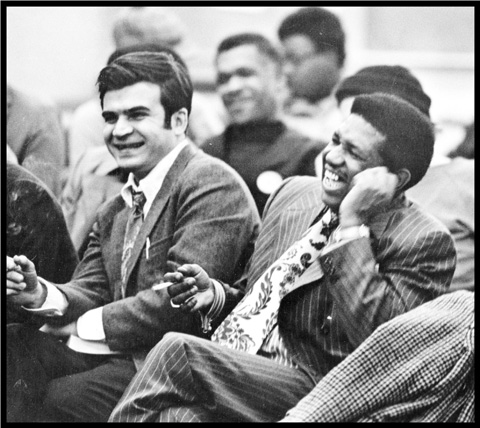

Ahdieh became involved with Harlem Prep through association with the Baha’i headmaster of the school, Ed Carpenter, who was known as a kind of “pied piper” because of his ability to get the students and faculty fired up to overcome obstacles. “He was in perpetual motion. A student was asked one day in the halls if he knew where Ed Carpenter was, and the student recommended that the visitor stand still because soon enough, ‘Carp’ [as Carpenter was known] would come rushing by,” wrote Ahdieh and Chapman in their book.

Ahdieh’s attraction to the school came from his time in Iran and his move to America. “My experience as an immigrant trying to eke out a living in hot and crowded kitchens, and the vilification I had weathered as a Baha’i in a small Iranian Shia Muslim town, made me open to trying to understand the struggle of black Americans against racism and the Jim Crow state,” he writes in another book, not yet published. Ahdieh started out as a math teacher, but soon became the assistant headmaster in charge of hiring faculty, among other responsibilities.

Hussein Ahdieh and Ed Carpenter at Harlem Prep

The school had a reputation for offering a more authentic education —“not a boring huge public school,” Chapman told IranWire. The students wanted something “less deadening,” he said.

It was the 1960s and a spirit of black militancy and counter culture was in the air. “A teacher whose course stunned Harlem Prep students was Yosef ben Jochannan. In his class, students — most for the first time — heard that Egypt, located on the continent of Africa, pre-dated Greco-Roman culture and the world of the Bible. Many black students were shocked to learn of ancient African contributions to civilization and to see ‘black’ people as having more than [just] a history of enslavement. This learning broadened their horizons, aroused their curiosity, and reflected the growing awareness about race and culture that was a part of the new generation,” wrote Ahdieh and Chapman.

Harlem Prep also wrestled with some of world’s most perplexing questions and concerns regarding education. “How do you educate children for free that are disadvantaged? It’s not at all obvious,” said Chapman. “How do you create a system that can educate people publicly, that can really be a meritocracy, [and] that is responsive to culture?” he asked, adding, “What should you teach in the classroom?”

Baha’is in Iran currently face similar issues regarding education, although in a different way. Baha’is are not allowed to teach at or attend university. The Iranian Baha’i community has met this discrimination by creating a secret underground university, the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education (BIHE), which the Not A Crime campaign works to highlight. Students at BIHE attend secret classes in the living rooms of teachers’ homes throughout Iran, as well as taking distance learning classes online with instructors around the world. They complete coursework in literature, architecture, psychology, accounting, and computer science, among other subjects.

Harlem Prep, which was funded by corporations and foundation grants, closed its doors in 1977 due to the economic downturn during that decade, despite efforts made by Ahdieh, Ed Carpenter, and others to keep it running. Ahdieh moved on to become the Director of Educational Opportunities at Fordham University in the 1980s, where he taught a class on Islam in the Black Studies department. He is currently working with Hillary Chapman on a book about Tahirih, a nineteenth-century Iranian poet, women’s rights activist, and a prominent member of the early Baha’i movement in Iran.

Leave a Reply