Source: www.buzzfeed.com

Canadian universities are now recognizing degrees from an underground school for the religious minority.

At each ring of his phone, Shakib Nasrullah and his family jumped.

The caller ID was blocked, but Nasrullah knew it was the government of Iran even before he answered. The voice on the other end told him to present himself at a location.

That morning, Nasrullah’s mother and wife accompanied him to an old one-level home, where he would be interrogated for hours.

His interrogator said he’d engaged in illegal activity, colluded against the Iranian government, and threatened national security.

But what exactly had Nasrullah done to land himself in the interrogation chair?

He’d been teaching psychology to students whom the government had banned from postsecondary education.

This was back in May 2011. Nearly six years later, Nasrullah, now 35, is doing his PhD in counselling psychology at McGill University — a long way from the Iranian prison where he was once held in solitary confinement.

“It’s really one of the most obvious cases of state persecution,” Heiner Bielefeldt said in Geneva in March 2013.

A Bahá’í father and son (left) in chains after being arrested with fellow Baha’is, in a photograph taken around 1896. Both were subsequently executed.

Bielefeldt — the UN special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief — spoke at a Human Rights Council session about the abuses Baha’is in Iran face across “all areas of state activity.”

The Baha’i Faith is an independent religion with an estimated 6 million followers worldwide. Baha’is practice the teachings of the faith’s founder, Bahá’u’lláh, who emphasized the fundamental oneness of humanity, God, and religion.

Since the faith’s founding in Shiraz in 1844, the Iranian government has persecuted Baha’is. Early followers were killed or exiled, with the violence continuing from one Iranian monarch to another.

Then came the Islamic Revolution in 1979, when the shah was overthrown. Violence against Baha’is refocused and escalated, with many imprisoned, tortured, and denied the right to work or marry.

Some families face more violence than others, but one barrier is universal: a ban from higher education.

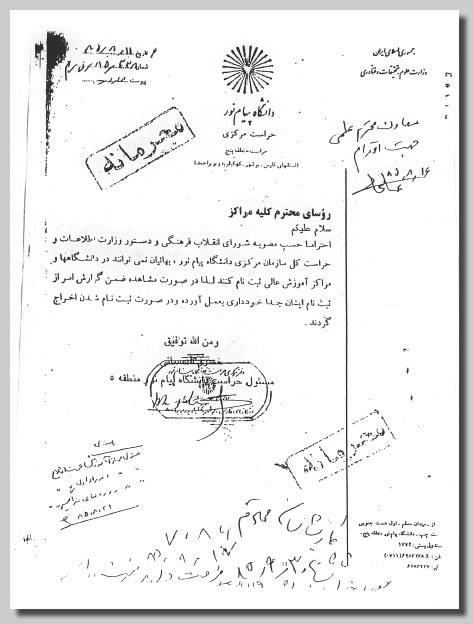

In response, the Baha’i community started its own underground university in Iran in 1987: the Bahá’í Institute for Higher Education (BIHE). It’s been classified as an illegal organization by the Iranian government, making any involvement in the covert operation perilous.

In 1998, before he’d set foot on Canadian soil, or in a prison cell, Nasrullah was in his last year of high school in a country where he had no right to higher education.

So he, like many Iranian Baha’i youth, turned to his only option: BIHE.

As he studied for his entrance exam on Tuesday, Sept. 29, 1998, the government launched raids across the country. By early October, the homes of 500 Baha’is who were helping BIHE were raided.

Equipment and records were confiscated, property was destroyed, and at least 36 staff members were arrested.

“They basically wanted to finish off the university,” Nasrullah said.

He recounted how quickly fear struck him when he heard the news — and then how quickly it faded.

“You get triggered very fast, because you’ve heard so many stories from your parents, from your other Baha’i fellows, of the raids, of the killing,” said Nasrullah.

“But it also passes really quickly because you know it’s futile, because you know those actions [by the government] have never ended up anywhere, because this community is not going to give up what belongs to it.”

After the attack, BIHE was shut down.

BIHE classes are held in the homes of volunteering Baha’i families at great personal risk. Students travel to Tehran — some from remote areas of Iran — for a week to 10 days of lectures. They’ll do this a few times each semester, which is five to six months long.

Class locations are revealed only a few days prior, Nasrullah said, and nothing BIHE-related is ever discussed over the phone.

Meeting more often is dangerous and difficult for out-of-town students. As a result, BIHE students are largely self-learners, which Nasrullah said can be quite lonely at times.

In-person classes were “the most exciting, the most rejuvenating experience,” Nasrullah said. But the excitement was always tainted by underlying anxiety. “Going to each class, you would be prepared that, well…you would be attacked, you would be raided.”

“She got extensions for some of her assignments,” he said.

Since it began, BIHE has grown considerably. It now offers 32 undergraduate and graduate degree programs and 1,050 courses, ranging from Persian literature to applied chemistry, according to its website.

After he completed his bachelor’s at BIHE, Nasrullah moved to Montreal with a degree from a university no one had heard of. But he had his sights set on McGill University’s master’s program in counselling psychology.

At first, the head of the program was skeptical.

“I totally understand her. She had a hard time believing that I actually know anything about psychology,” he said, laughing. He said she gave him an oral quiz and soon realized he knew his stuff.

He became the first BIHE graduate to complete a master’s degree at McGill.

Now McGill is on a list of 81 postsecondary schools around the world that accept BIHE graduates even though Iran calls the school illegitimate.

In Canada, that list includes the University of British Columbia, Queen’s, Carleton, the University of Manitoba, Concordia, the University of Ottawa, and McGill. In the United States, the list includes Harvard, Yale, Columbia, and Johns Hopkins.

Schools in India, the UK, Ireland, Norway, Finland, France, Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Australia, and New Zealand also accept BIHE graduates.

However, proving to universities that BIHE degrees are legitimate is an “arduous process,” Nasrullah said, and other BIHE students and administrators interviewed agreed is a serious barrier.

There are inconsistencies in the ways different schools assess foreign degrees, which can trap BIHE graduates in a catch-22, says 30-year-old Milad. Milad asked to have his last name omitted to protect relatives still living in Iran.

When Milad — a BIHE graduate — applied for schools in Canada, he was told to give his credentials to an external evaluator, such as World Education Services (WES) or the International Credential Assessment Service of Canada (ICAS) — companies that assess international credentials. When he approached WES and ICAS, Milad said they told him to “just go and bring officially recognized transcripts.”

“How can I bring my transcripts to a government who denied my human rights in the first place?” he said. “They don’t recognize me as a human being. How can I ask them to recognize these papers?”

Since BIHE wasn’t on the Islamic Republic of Iran’s list of officially recognized universities, WES and ICAS didn’t recognize Milad’s transcripts, he said. He was forced to start from scratch, even though he had completed a bachelor’s and a master’s degree at BIHE.

He’s now in the second term of an electrical engineering degree at a Canadian college.

In Canada, accreditation depends on the university’s own policies. Milad said evaluation agencies need to better “understand the unintended consequences” of rejecting BIHE transcripts — a point that all students and Baha’i representatives interviewed agreed with.

In the past, some universities have been receptive to BIHE students, recognizing their special circumstances, said Corinne Box, the director of government relations for Baha’i Community of Canada. One such school is Carleton University.

In 1998, Carleton launched a pilot project that allowed BIHE graduates to prove they had in fact obtained the equivalent of an undergraduate education, Box said.

The pilot project, which started with two students in the Department of Civil Engineering, was a success. It grew to include several other Canadian universities, said Carleton’s manager of public affairs Beth Gorham in an email.

Of the 67 BIHE graduates admitted to Canadian universities between 1998 and 2008, Gorham said 36 were admitted to Carleton.

Most BIHE students have excelled in their studies, Gorham said. Several students received scholarships, and others were “nominated for the Senate Medal in recognition of the calibre of their work.”

The difference between a BIHE student’s experience in Iran and a student of, say, McGill is vast. The activities that usually accompany university life — strolling along campus, studying in libraries, joining clubs, socializing with friends in public — are missing.

Among the most startling differences is that BIHE is entirely volunteer-run, with faculty and administrators unpaid. Students pay only the equivalent of $50 Canadian per semester, which goes toward photocopies and materials, according to Nasrullah.

“My dad, for example, was fired from his job because of being a Baha’i and he had to come back to his dad’s farm,” he said.

When BIHE graduate Arman Roshan and his family tried to open a store for his mother to run in Iran, local authorities refused to give them a licence.

“Your dad already has a job. You don’t need another job to survive. As a Baha’i you don’t need to be rich; you just need to survive,” he recounted the authorities saying.

With an economy that’s largely dependent on oil, the government is a major employer in Iran — and one that’s obviously unwilling to employ Baha’is.

With few job opportunities — and a lifetime of persecution ahead of him — Roshan decided to smuggle himself out of Iran to Turkey, where he sought refugee status. He waited in Turkey for two years before Canada accepted him.

Supplied

Arman Roshan speaks at an event for Education Is Not a Crime — a campaign that raises awareness about the situation of Baha’is in Iran — at Carleton University on March 30, 2016.

“You have to say bye to a lot of your relatives, your family, your friends, and you know you might not see them again,” he said. “I said bye to my grandfather and grandmother, and both of them passed away.”

When he finally received his acceptance letter from the University of Ottawa for their structural engineering program, he said it felt validating.

“You also feel like, Hey, that thing I did for like five years back home, it’s worth something.”

Though he knew there was no way he’d be accepted, Milad applied for Iran’s standardized university entrance exam in 2008.

Forms at the time required applicants to indicate their religion, with only four options available: Muslim, Christian, Jewish, or Zoroastrian — an obvious barrier to Baha’is.

Then, under pressure from the United Nations and Baha’i communities, Iran removed the question and allowed Baha’is to apply to the entrance exam.

“They somehow changed their tricks,” Milad said.

“When you apply — despite the fact that all your documents were complete — they sent you a message that your documents are not complete, and as a result you’re not allowed to take part in an entrance exam.”

“What’s amazing,” he said, “is that all Baha’i candidates received the same message.”

When the international community brought a new wave of pressure, the Iranian government responded that, no, they had in fact admitted Baha’is into universities.

From the hundreds of Baha’i students who applied each year, Milad said only around 10 were admitted.

“After a few terms, they expelled them — one by one.”

In the days leading up to his final exams in university, Roshan got a call from a fellow Baha’i.

His friend had gone online to check his exam times, only to find he was no longer enrolled in any courses. Roshan checked his own account and found he was in the same boat.

“It was only a matter of time,” he said nonchalantly.

The pair went to campus for an explanation. They were told to go to Tehran to get answers from an education official.

“We talked to a guy and he told us verbally that we can’t continue our education at university because we’re Baha’is.”

Roshan, then in the mining engineering program, had been part of the first group of Baha’i students universities had seemingly started to accept. It soon became clear that it was only a front to pacify the international community, he said.

After completing his master’s degree at McGill in 2009, Nasrullah returned to Iran.

From the beginning, he said he planned to return and serve BIHE as a teacher.

“I owed it to those people,” he said. “That was the only hope for a lot of people, and I could not turn my face away from that.”

He arrived in Iran two days after the controversial reelection of then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

“I could not recognize Tehran. There were fires in the street,” Nasrullah said.

As Ahmadinejad took his oath of office, hundreds of riot police officers clashed with protesters outside parliament. Under his presidency, attacks on Baha’is in Iran ramped up, according to the US Commission on International Religious Freedom.

Despite the danger, Nasrullah immediately began teaching at BIHE and worked as a counselling psychologist at a clinic in Iran. A few months after he returned, he got married.

Shakib Nasrullah and his wife, Elham Paiandeh.

Nasrullah rushed home from work, relieved to find that his house hadn’t been raided. He and his family began to burn the evidence, setting students’ papers and documents ablaze in a metal container in their backyard.

“We were lucky … that our house wasn’t attacked, otherwise there were so many names that would have been captured,” he said.

Soon after burning the evidence, Nasrullah was brought in for interrogation at the old house — located on Baradaran Mozaffar Street in Tehran.

Stepping inside, Nasrullah said he was filled with a sense of nostalgia, as though the house’s walls held the history and joyful memories of its past family. But that nostalgia was mixed with terror, as armed guards stood watch and screams echoed through the house.

Other Baha’is were inside, and he could hear a particular contempt for Baha’i women during interrogations.

Curtains separated them from each other, but he said he could hear every word.

“They wanted people to hear … to create fear.”

“We would hear that the interrogators were really mad at us for sending news [of our treatment] to other countries,” he said.

Every few days, Nasrullah received a threatening call to bring him in for further interrogations. Then one day, officials said he and his friend had to come to the prison.

“We just want to ask some questions. Nothing special. You’ll be back in a few hours,” he remembered them saying. He and his family knew he wouldn’t be back so soon.

“We went to a meeting. My friends were all there and we were joking about it. We had spirit about it. I mean, it’s the story that we’ve all grown up with — the story of prison, fighting for what you believe in — so we were making jokes.”

“But at the same time, we knew we’re not going to come back.”

Danger is ever present for students, but the stakes are much higher for BIHE professors. Many have received prison sentences of four to six years.

“You can’t describe this feeling [of knowing] that someone is in jail for five years… just because he or she tried to teach you a course,” Milad said.

The day Nasrullah went to prison, he was one of four educators brought in. He was faced with the same interrogator from the old house, though his tone had become considerably harsher.

“We are going to keep you forever … we can do whatever we want to you,” he said the interrogator told him.

“God does not exist here … I am your God now.”

“And he was right,” Nasrullah said.

He was forbidden from contacting anyone and stayed in solitary confinement for eight days — the walls of his cell covered in writing by previous prisoners.

“You could hear people screaming and shouting under torture… begging them to let them go,” Nasrullah said.

Ten days later, they let him out. Two of the teachers, including Nasrullah, were allowed to leave, while they kept the other two.

“We never knew why,” Nasrullah said, though he suspects it was because the other two were well-known psychologists with greater involvement in BIHE.

The night they were arrested, Nasrullah said state-run media in Iran claimed they were fake psychologists trying to convert patients into Baha’is.

At the encouragement of his former supervisor at McGill, Nasrullah applied for his PhD and got out of the country before his court date.

Three teachers who were imprisoned at the same time — Kamran Rahimian, Kayvan Rahimian, and Faran Hesami — received sentences of four to five years.

Kayvan Rahimian remains in prison today.

Now in Montreal, Nasrullah has two more years left of his PhD — but being thousands of miles away from Iran hasn’t stopped him from helping BIHE. He remains a teacher at BIHE, and runs bachelor’s and master’s courses for the school over the internet. He also teaches a course at McGill.

There’s a pragmatism to the way he recounts his experiences, with laughter at times punctuating stories. Yet as Nasrullah’s interview wrapped up, his tone turned somber. Quietly, he expressed a hope that by telling his story he could repay some of his debt to his friends in Iran and those who remain in prison.

Leave a Reply