Source: www.washingtonpost.com

The Bahai faith is one of the youngest world religions — on Sunday, it will celebrate the birthday of its messenger, Baha’u’llah, who was born just 200 years ago. But to the kids bouncing off the purple-painted walls on 14th Street, that’s ancient history.

“My name is Baha’u’llah Junior!” Menkem Sium calls out jokingly. “My dad is 200 years old!”

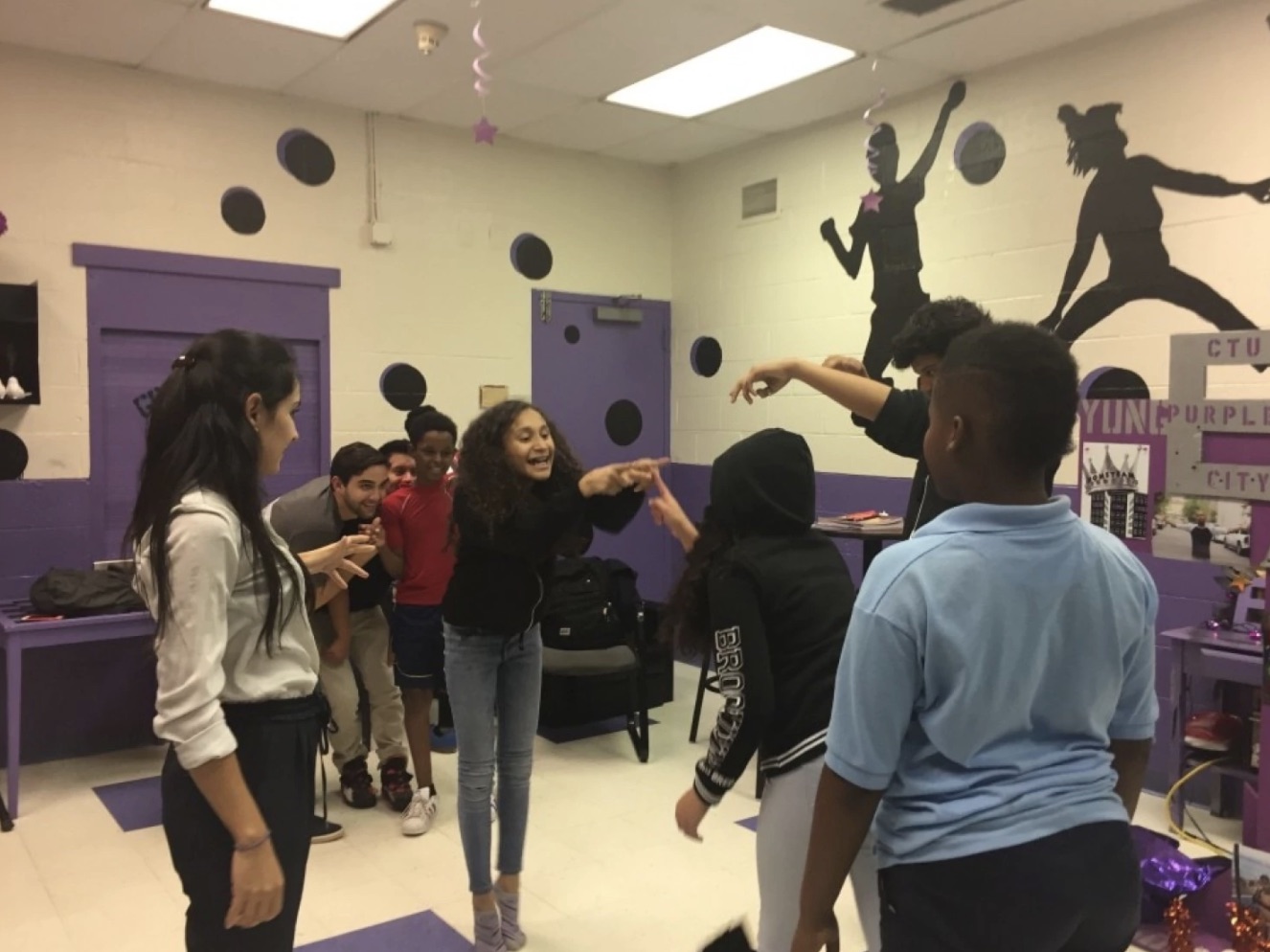

Baha’u’llah, who was born in Tehran in 1817, might not recognize the religion based on his teachings today, in its vibrant form in the District. Fourteen youth groups teach crafts and games and vocabulary to about 120 teenagers, including the enthusiastic Sium. About 190 younger children participate in 20 Bahai children’s classes. All over the city, Bahai devotees and other curious adults gather in private homes and a stately 16th Street NW worship center, each night of the week, for 35 different regular study circles and 45 devotional meetings.

On Sunday, local followers of the faith will congregate for an extravaganza of artistic performances in English and Spanish, and plenty of food, to celebrate the 200th birthday of the visionary leader behind it all. Their celebration will focus on racial unity: one of Baha’u’llah’s foremost goals, which remains elusive and just as relevant today.

Baha’u’llah was born two years before a man who eventually came to call himself the Bab. The Bab announced in 1844, at age 25, that he had come to proclaim the arrival of the next great messenger, a man who would follow in the tradition of earlier religious messengers — Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha, Krishna, and so on. Hundreds of people became followers of the Bab, before he was executed for his beliefs in 1850.

Thirteen years later, Baha’u’llah revealed himself: He was the messenger whom the Bab had promised. He too was imprisoned and harassed for much of the next 40 years, while he wrote the works that became the basis of the Bahai faith. The religion places a heavy emphasis on equality, and Baha’u’llah’s writings taught about harmony among men and women, people of all races, science and religion, and all forms of faith.

Today, gorgeous Bahai temples stand on each continent but Antarctica, as architectural icons in places from Cambodia to Uganda to the suburbs of Chicago. Bahai communities — some still persecuted in the Middle East, many thriving in tolerant nations — gather for worship in almost every country. And here in Columbia Heights, a raucous group of teenagers is learning to pray.

“Oh Lord,” Anais Basora, 11, reads aloud. “Confer thy bounty. …”

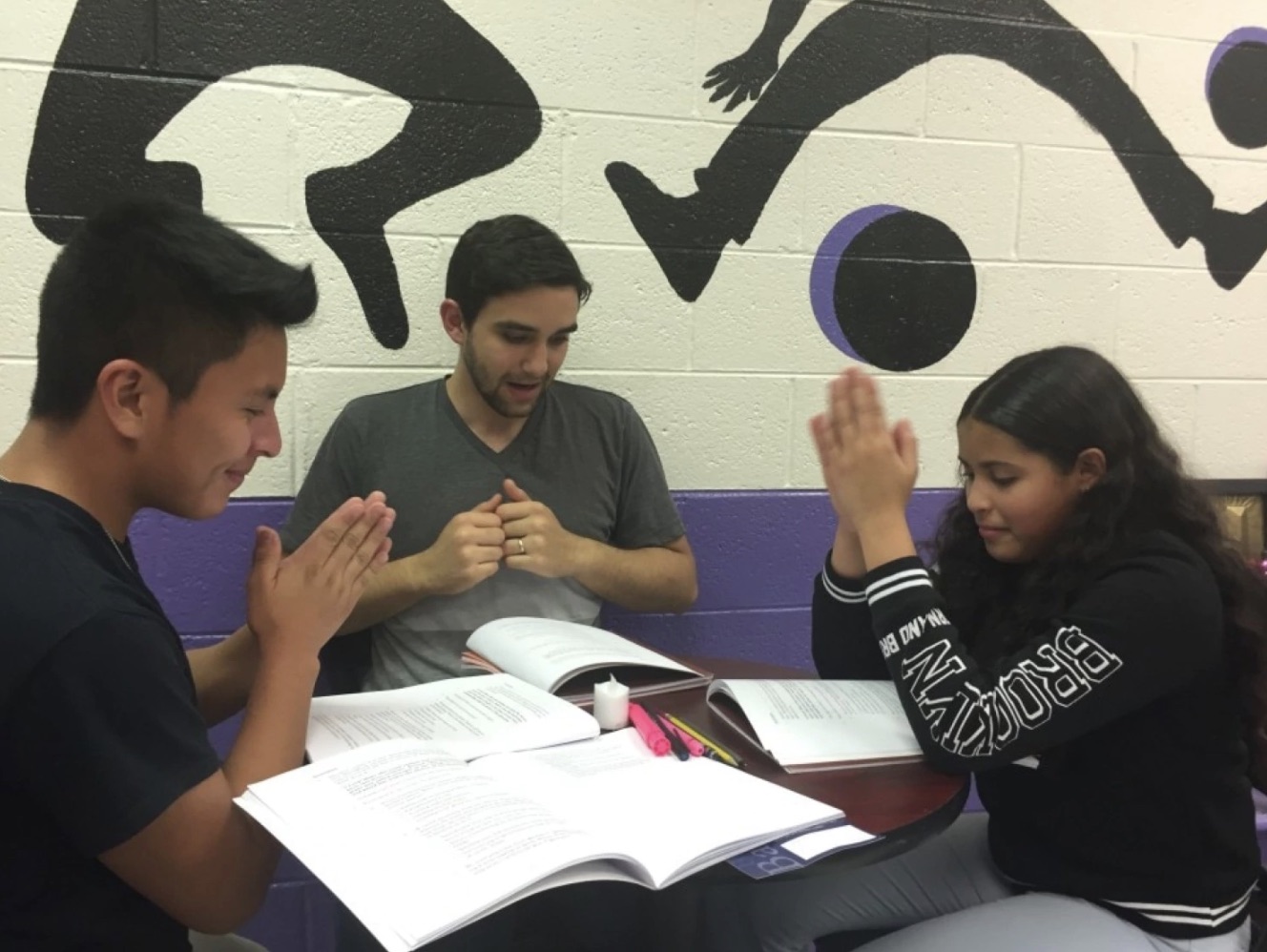

Navid Shahidinejad, the leader of this Bahai youth group meeting at the Rita Bright Community Center, prods Basora, “Do you know what ‘bounty’ means?”

Basora isn’t Bahai. Most of the teenagers in the “junior youth empowerment” groups run by Bahai believers in the District are not members of the faith, based on the Bahai tenet of treating equally people of all religions.

“When I look at the revelation of Baha’u’llah and its purpose to unify mankind, I find that this revelation is for everybody, and all are welcome to participate,” said Maryam Esmaeili, a leader in the District’s Bahai community. She runs her own youth group using the same Bahai curriculum at a second location in Columbia Heights; this week, she helped out in Shahidinejad’s group as well. “Universal participation is absolutely necessary to build a better world. It’s not in the hands of only Bahais.”

Esmaeili and Shahidinejad said the intent of opening these youth groups to nonbelievers isn’t to convert the teenagers; after all, their faith preaches that all religions are equal. That being said, they encourage children and parents who are interested in Bahai practices to learn more outside the youth group. The Bahai focus on racial equality is often what interests parents, who sometimes start learning the prayers with their kids and check out events at the 16th Street center.

The religion is too small for the Pew Research Center or other polling groups to have gathered much data on it, but the Bahai International Community says there are more than 5 million adherents worldwide and about 340 in the District, with additional Bahai communities in the Maryland and Virginia suburbs. On Sunday, the community will host its major celebration of Baha’u’llah’s 200th birthday at Woodrow Wilson High School.

Abdul Hill, the athletics manager at the Rita Bright Community Center, said he likes having the Bahai youth group there since it introduces the children to another culture and since the education on how to pray helps them deepen their own faith, whatever their religion might be. “A lot of them don’t go to church,” Hill said. “Something like this is very big for them, just having that structure as a human being on Earth.”

On Thursday night, after the teenagers practiced memorizing a prayer drawn from Baha’u’llah’s writings and played an energetic name game, they sat down in a circle to think up ideas for their next service project, a core part of the Bahai curriculum.

The kids have decided that they want to visit children with cancer. Shahidinejad mostly lets them think through their ideas on their own.

“I know that they like the jello and the pudding,” Sium, 13, says. One teen suggests that they bring video games to the patients, and Basora suggests bringing teddy bears. “I’ve got a bunch,” she says, then she thinks better of it. “No, I’m not giving them.”

One of the adults suggests writing cards, and Basora says, “No, that’s for the vegetarians.”

There’s a rare moment of silence. All the kids stare at her for a moment, then figure out what she meant: veterans. Good-natured giggles ripple around the circle.

This process is central to the curriculum, which focuses on social justice. “The revelation of Baha’u’llah, which talks about the oneness of mankind, is so grand in itself,” Esmaeili said. “That is where this idea of unity becomes more possible: just being able to support youth and middle-schoolers in developing an understanding of their twofold moral purpose, that they have qualities that can be used to serve others.”

Esmaeili, who grew up in a Bahai home in El Salvador, said she often meets people who are surprised to learn about the Bahai community running so many programs for people of all ages in the District and many other American cities. One of the first assignments in the adult-study circles is to visit a friend and share a prayer with him or her, she said.

“Sometimes that sounds very odd, in a city like D.C., that people are actually doing this,” she said. But the kids in the youth group don’t seem to find it odd at all.

______

Leave a Reply