Source: bbc.com

Pejman Akbarzadeh

Translation by Iran Press Watch

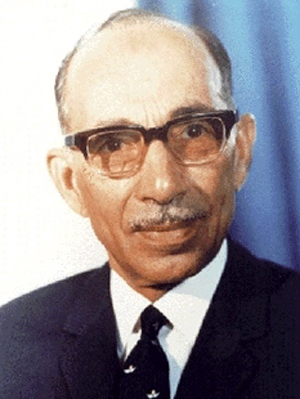

In the 1970’s, Iran Air (known in the country as HOMA) had garnered the title of “fastest growing” among the world’s airlines. According to Encyclopedia Iranica, Iran Air was the highest earning company in Iran after the National Iranian Oil Company, and had been recognized as one of the world’s safest airlines by the Flight Safety Foundation. These achievements were connected to the name of General Ali-Mohammad Khademi (1913-1978), who headed Iran Air for 16 years. His service ended with an abrupt resignation a few months before the Islamic Revolution.

General Khademi was killed forty years ago in his home. Despite witness accounts by his wife and the soldiers assigned to his home, the government controlled media called his murder a “suicide”, although several international media outlets, such as the New York Times, reported on his murder. Among Iranian Baha’is, General Khademi held the highest ranking leadership post in a public institution. His religious affiliation, which was not a secret, was the cause of fierce opposition by a number of Muslim clergy.

A Forgotten Murder

The murder of Ali-Mohammad Khademi, and who was responsible for it, are rarely mentioned any more. A few months after his murder the Islamic Revolution succeeded, and a large number of the former government’s officials were sent to the firing squads. It seems that amidst the widespread murders and the country’s tumultuous atmosphere, the fate of the head of Iran Air was soon forgotten.

Cyrus Ala’i, a former professor of University of Tehran and a friend of General Khademi, has spent several years reviewing documents related to the murder. With the help of the Khademi family, he first published a collection of the documents from Tehran’s Military Command in the journal Iran Nameh in the spring of 2015.

In one of the documents, it is recorded that three bullet casings were found next to Khademi’s body. Based on this document and as reported by the officer who inspected the crime scene, General Khademi “was assassinated by a group of at least three”; the coroner also confirmed his “murder” by a bullet to the back of the head. The document also names three members of “the joint anti-terror committee”, one of whom was identified at the Military Command by Bahiyyih Moayyed as the shooter of her husband, General Khademi.

Despite these individuals’ identification and arrest by the Military Command, none of them were tried or punished. Later on, The National Security and Intelligence Agency (SAVAK) detained Bahiyyih Moayyed for about one month to force her to declare that her husband had committed suicide. She refused.

Cyrus Ala’i says: “The government apparatus was so nervous in those days that it would resort to anything to calm the situation. The murder of General Khademi – as one of the most prominent Baha’i figures – was one of those tactics which not only did not help to restore calm, it actually infuriated the people and emboldened the clergy.”

Ali Mohammad Khademi Among Eminent Persians

In his book “Eminent Persians” (published in 2008), Abbas Milani writes a special article on General Khademi. The article says: “After graduating from the Military Academy and the Air Force Flight School, Khademi attended the British Air Force Academy, and was the first Iranian to obtain a commercial pilot’s license there.” Mr. Milani considers General Khademi’s resume to be a prime example in contemporary Iranian history of how courage and integrity together with a policy of meritocracy can be effective in a society.

On the 40th anniversary of General Khademi’s murder, Abbas Milani says he has not come across any precise documents demonstrating that the Shah’s security apparatus had a role in Khademi’s murder. He adds: “In my opinion, the evidence indicates that religious forces had role in this event, but ultimately tried to blame SAVAK for it. Without having a network within the government, Khademi raised Iran Air from nothing to the highest level. This achievement was a thorn in the side of those who could not stand this success, who today deny Baha’is even a right to higher education.”

The Director of the Iranian Studies Program at Stanford University adds: “Regarding General Khademi, even his critics did not accuse him of financial misconduct. During his leadership, Khademi focused his efforts on making Iran Air independent of foreign pilots, and he was well known for his strict regulations for hiring competent pilots and preventing flight delays, even to accommodate high ranking officials.

Differing Views on the Shooters’ Identity

The media during the Shah’s time unanimously called the murder of General Khademi a suicide. Abbas Milani does not offer a clear reason for this, but to a degree attributes it to the crisis-stricken atmosphere of Iran in those days. He says: “It is now perfectly clear that religious forces played a role in the arson of Cinema Rex, but at the same time, when Darioush Homayoun announced this finding no one believed him. It was the same with the murder of General Khademi. The Shah’s regime had lost its credibility, and whatever it said was used against it.”

Cyrus Ala’i, however, completely denies the role of religious forces, and believes that based on the documentation, the role of the “anti-terror committee” is quite evident. Mr. Ala’i meanwhile insists that Mohammad Reza Shah was unaware of the actions of the anti-terror committee, and the committee, which had gained extraordinary power at the time, used its influence to prevent the Tehran Military Command from following up with prosecuting the perpetrators.

The Period at the Helm of Iran Air and IATA

In 1962, after completing his studies in Iran and Britain, and several years of working, General Khademi was appointed head of the newly established Iran Air. Shortly afterward, he also completed a graduate program in air transportation management in the American University in Washington.

In his book, “The History of Iranian Air Transport Industry”, Abbas Atrvash points out that at the time Iran Air owned 13 small airplanes and had around 750 employees. By 1978, those figures had increased to 37 Boeing aircraft and 12,800 employees.

Along with expanding Iran Air, in 1970 – for the first time in Asia – Iran hosted a meeting of the International Air Transportation Association (IATA). That same year, General Khademi was seated as the Association’s president for one year, the first Asian to hold that post.

During this period, the Iran Air flights were expanded from the Middle East and Europe to the Far East and North America. While at the helm of Iran Air, Khademi demonstrated anew his inclination in favor of perpetual learning and being up-to-date. Establishing continued education courses for employees in Tehran and organizing management training courses throughout Iran were indications of this attitude. For his achievements in the commercial aviation industry, Northrop University in California awarded Khademi an honorary doctoral degree in 1977.

Confiscation of Property and an Open Case

Following the Islamic Revolution, Khademi’s property in Tehran was confiscated, but the case of his murder remains open. In official correspondence obtained from Tehran, it is indicated that if at some point his heirs wished to pursue the case, the file could be reopened.

In 2004, Monib Khademi, the eldest child of General Khademi, travelled to Tehran in an attempt to prevent the case from being closed, but did not succeed. He says: “I was told I could not do anything about this case, and the matter of the confiscation of property is based on the order issued by Ayatollah Khomeini related to confiscation of the properties of Baha’is.”

Monib, together with his sisters Mona and Minoo, has compiled a collection of documents regarding his father’s activities and assassination which is soon to be turned over to Stanford University for use by researchers.

General Khademi was buried in the Baha’i cemetery in Tehran, which was bulldozed some time after the Islamic Revolution.

June 24, 2024 3:23 am

Mr. Atrvash’s History of the Iranian Air Transport Industry should be read with much caution, at least in so far as its account of Iranian Airways, the 1st, pioneering, private, commercial airline company co-founded in 1944 by Reza Afshar and Abolqassem Ebtehaj that Khademi inherited when it was nationalized. A more accurate and valuable history of aviation in Iran is found in Eduard Khachikian’s two-volume book, From Mehrabad to Los Angeles.