Source: iranwire.com

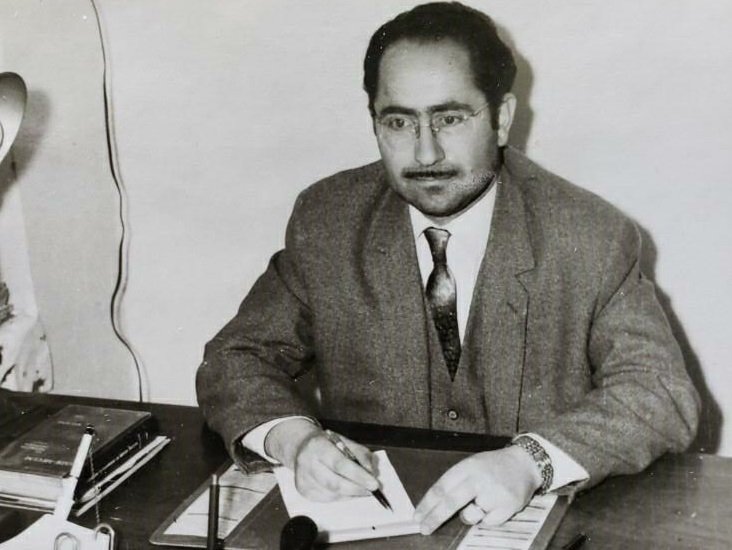

Kian Sabeti

Health workers are on the front line of our defense against the coronavirus pandemic – including hundreds of Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. But they are not in Iran; instead, they live in countries around the world, treating their patients, where they are admired and praised by the people and governments of the countries where they live. The one country where they cannot do their work is Iran.

Many of these doctors and nurses – who studied and served in Iran – lost their jobs after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. They were expelled from the universities and their public sector jobs, barred from practicing medicine, jailed and tortured, and a considerable number of them perished on the gallows or in front of firing squads.

The crime of these Baha’i doctors, nurses and other health workers was their faith in a religion that the rulers of the Islamic Republic believe is a “deviant” faith.

In a new series of articles, called “For the Love of Their Country,” IranWire tells the stories of some of these Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. The following is the story of Dr. Masroor Dakhili, a multi-talented clinician who served as head of the respiratory diseases section in the largest hospital of Mahabad in 1967 but was executed after the Islamic Republic came to power.

If you know a Baha’i health worker and have a first-hand story of his or her life, let IranWire know.

Farideh heard the clucking of a chicken from the front yard. She opened the window and saw her husband walking towards the building with a chicken in his hand. “They paid you with a chicken again for your vist?” she asked. “Leave it in the backyard! What are we going to do with all these chickens?” Dr. Masroor Dakhili nodded with a smile.

Dr. Dakhili, a beloved Azarbaijani doctor who had worked for years in many small and large cities across Iran’s Azerbaijan region, was shot on July 29, 1981, together with eight other Baha’is. He was 58 years old and his crime was his belief in the Baha’i faith.

An engineer who became a doctor

Masroor was born to a Baha’i family on November 10, 1923, in the city of Maragheh in the province of Azerbaijan. He went to elementary school in the city of Salmas and then attended Tamaddon high school in Tabriz where he earned his diploma at 18 years old. He was an outstanding student.

Masroor’s father was a high-ranking employee of the Ministry of Post and Telegrams who passed away when Masroor was 15. He was later appointed to a role in the same office – to help increase the family income. The Ministry sponsored him to study at Pahlavi Beeseem college where he studied to become an electrical engineer.

Dakhili’s new degree came with responsibilities and he was asked to manage the newly-established radio of Tabriz. He also applied for a Masters degree from Beirut University but he was not able to attend the final exam in Beirut.

One day, Dakhili’s mother told him that, when he was a child, his own father wanted him to become a doctor but that life pushed him to engineering rather medicine. Learning this inspired the young Dakhili to consider the same idea, given his love of learning; so at the age of 25, so when the University of Azarabadegan opened in Tabriz he enrolled in the medical school.

Masroor graduated from medical school with excellent grades in 1954 and was hired by the Red Lion and Sun Society Hospital in Tabriz.

Dr. Dakhili later decided to get married. He married Farideh Sheikholeslami in 1956. The couple had three children: Farah, Fariba and Hossein.

Working in Miandoab and Mahabad

Dr. Dakhili’s family moved to Miandoab in 1957 and lived there for 10 years. He was hired by the Ministry of Health to work in the city’s hospital. He converted part of his home to serve as a clinic and offered consultations to patients after his hospital shifts. Many of his patients were poor and paid for their consultations with chickens and roosters.

Dr. Dakhili would leave a special mark on the prescriptions of some of his poorest patients. The mark was a signal for the pharmacy near his clinic to give a discount to the patient without them knowing. Dr. Dakhili then paid the difference to the pharmacy out of his own pocket.

“Many women giving birth, as well as other patients, were brought to our home in the middle of the night,” Hossein Dakhili, Dr. Dakhili’s son, told IranWire. “Dad accepted them with kindness. Mother helped him with deliveries or diagnosing and treating the patients.”

The Ministry of Health had sent Dr. Dakhili to Tehran for an advanced workshop on respiratory and digestive diseases when a tuberculosis epidemic broke out in Miandoab region while he lived there.

A former resident of Shahin Dej says Dr. Dakhili visited the city once or twice a week and treated patients from dawn to dusk.

Shahin Dej was a small city near Miandoab that had no health facility. Patients had to rent a car to visit doctors in nearby towns – the closest health center was three or four hours away. Dr. Dakhili’s visits saved the patients the trip. Whenever he visited Shahin Dej, there was a long line of patients in front of where he stayed.

During one of these visits, the Khan, leader of a nearby tribe, sent some men to fetch Dr. Dakhili to help with the delivery of his daughter-in-law. Dr. Dakhili’s wife and their host in Shahin Dej advised him against going and told said that he could be in danger. But Dr. Dakhili said he was a doctor and he needed to go wherever his patients needed him. He went and the birth was successful.

The next day, the Khan again invited Dr. Dakhili. The doctor did not want to go, this time, but now his hosted convinced him him that if he did not the Khan may take it as an insult.

Dr. Dakhili and his wife visited the Khan. After lunch they were presented with a gift of money, a firearm and bullets wrapped in silk cloth.

The doctor asked to see the infant – he then gave the money to the infant as a gift. Dr. Dakhili did not accept the firearm and told the Khan: “Baha’is are not allowed to own firearms and I don’t have a use for it anyway. A good friend like you is better than any firearm to keep me safe.”

Dr. Dakhili became the head of the respiratory diseases section in the largest hospital of Mahabad in 1967. His workload at the hospital did not leave him enough time to also run a clinic. But his kindness, skill and attentiveness during diagnoses and treatments made him a popular and widely-liked doctor. Older citizens of Mahabad still recall him with fondness – even decades after his death.

Returning to Tabriz

The popularity and fame of a Baha’i in a small Kurdish town finally caught the attention of Savak, the secret police under Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi’s regime, before the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Pressure from Savak eventually forced Dr. Dakhili and his family to move from Mahabad to Tabriz.

Dr. Dakhilis’ family returned to Tabriz in 1976 after living in Mahabad for nine years. Dr. Dakhili worked in a respiratory hospital on Shah Goli road in the morning. A few days a week he was in a clinic by the railroads. He treated his patients in his personal office in Shahpour street in the evenings.

Dr. Masroor Dakhili retired in 1979 a few months after the revolution. He spent most of his time in his office which was always filled with patients. Patients came to see him from Tabriz, surrounding cities and even from Mahabad and Miandoab.

Arrest, execution and confiscation of assets

Dr. Masih Farhangi, a friend of Dr. Dakhili and a popular Baha’i doctor from Gilan province, was kidnapped by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards in Tehran in December of 1979. He was executed in June 1981 for the crime of being a Baha’i.

When Dr. Masroor heard the news, he told his wife that his fate would be the same as Dr. Farhangi: “If I don’t come back home one day, you should know that I have been arrested,” he said.

Dr. Dakhili moved to Tehran to protect his family after this incident. He later heard that the Revolutionary Guards had been looking for him in Tabriz and that their family home there had been confiscated. This moment marked the beginning of Dr. Dakhili’s life in hiding. This skilled and experienced doctor could have treated hundreds of patients; instead, he was forced into hiding in Tehran because of his religious beliefs, and because of the persecution of the authorities.

Hossein Dakhili, Dr. Dakhili’s son, recalls that on July 6, 1981, his parents and he drove to Bandar Anzali to visit his older sister. They were followed by a white car all the way to the city of Manjil.

The traffic police stopped the Dakhilis in Manjil and a guard got into their car. The guard rode with them to Rudbar where Hossein and his mother were separated from Dr. Dakhili and were sent to Bandar Anzali. Dr. Dakhili and the car were taken to Rasht and then, five days later, to Tabriz. He was then imprisoned in Tabriz.

After spending eight days in solitary confinement, Dr. Masroor Dakhili, together with eight other Baha’is, were shot on July 29, 1981. There is no information on the trials of these executed Baha’is which were held in secret. The accused did not have access to lawyers. A will of Masroor Dakhili, dated July 28, was given to his family. It is likely that it was written after the trial and after the execution sentence was handed down. A few days later, the Kayhan newspaper announced that nine Baha’is accused of spying had been executed. No evidence was ever presented.

The Revolutionary Court of Tabriz declared that all belongings, assets and bank accounts of the executed Baha’is were confiscated by the Islamic Republic government.

Dr. Masroor Dakhili was also known as a witty person with a smile famous among his friends and colleagues. His smiling face was noticeable in his photos and it was the reason he was popular among his friends and patients.

Leave a Reply